Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly

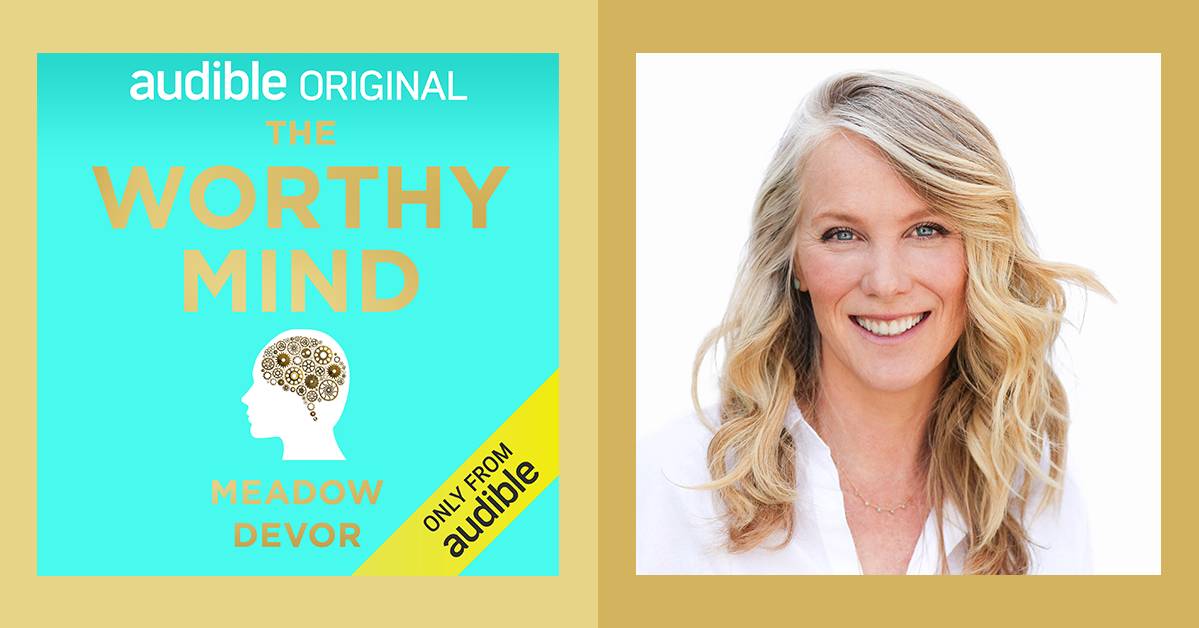

Rachael Xerri: Hello. I'm Audible Editor Rachel Xerri and with me today is author and personal development teacher Meadow DeVor. We're here to talk about her latest Audible Original, The Worthy Mind. Welcome, Meadow.

Meadow DeVor: Oh, thank you so much for having me.

RX: We're so excited you're here. So, my first question for you today is that you've touched so many people through your first Audible Original,The Worthy Project, and I'm so curious, did you receive any listener feedback or insights that inspired you that you'd like to share with us?

MD: Yes. I got a lot of really, really sweet emails and, surprisingly, from all over the world, which I wasn't expecting. I was really just expecting mostly US or even English-speaking countries. I got several from South America, from Mexico, from Australia. It was just very sweet. More than anything, what I was hearing was, "I've never heard somebody explain how I felt," and it made me realize, okay, one, that I wasn't alone, personally, in my own experience, and then also that there's this truth underlying this worthiness issue. When I went to write that first book, that word, “worthy,” was the word for me. It wasn't self-esteem. It wasn't confidence. It wasn't that. It was worthy. It was this deep-in-my-bones feeling that I wasn't enough. And that's what I wanted to capture, and it sounds to me like a lot of people felt that too.

RX: Certainly I know I connected to it the first time I listened as well. So, on that note, in The Worthy Project, you focused on how to stop undervaluing yourself and start investing in yourself. How does The Worthy Mind build on your earlier advice?

MD: So, The Worthy Project is really going through the backdoor of somebody's psyche in a way that you're hacking your behavior. Like, you're actually changing how you behave in order to invest in this idea of self and broaden this idea of self. And so, as you collect more self, you collect more worth. I wanted to make an idea accessible as much as possible that there are corners of your mind that you're just not using, you're not aware of, and how much those ideas that you've pushed away actually inhibit how much territory you're living in your life or experiencing in your life. So, when you're living as a fraction of yourself, you're only experiencing a fraction of what you're worth, and I wanted to capitalize on that idea. And how do we push ourselves all the way out to the edge so that we really, instead of trying to deem parts of us not good, accept those parts and realize that they're necessary and helpful.

So, The Worthy Mind title might sound like, “Oh, this is going to be some happy thoughts to make you feel good about yourself,” and it's actually not that. It's how to really go into the darker territory that you haven't seen and excavate good old stories about yourself so you can find out who you are—the good, bad, the ugly, all of it—and really own it.

RX: And you touched on this a bit already, but self-acceptance is such a huge theme in this audiobook, and you talk about how worthiness isn't about becoming the best version of yourself, but rather acknowledging that the you who you are now is already deserving. Can you give our listeners a sneak preview of how The Worthy Mind will help them find their way to this truth?

MD: Yes. So, that feeling of not-enoughness usually comes in the form of, "Oh, if I was smarter, or if I had more money, or if I had a boyfriend, or if I had a girlfriend, or if I had a house, or if I had the right job." You know, it's like, what I don't have will make me worth more. If I can just better myself, if I can just improve that last little fragment of myself, then I'll feel this feeling that I'm trying to get to.

"As you collect more self, you collect more worth."

When I was writing The Worthy Mind, it was really interesting because some of the things I worked on in real time, and some of the things I had worked on before I started writing it. One of the stories that I worked on in real time was the food story and it took me months while I was writing it to really go, "Okay. What is this? What is this thing in me that I really don't want to have to talk about, I really don't want to have to share, I really don't want to have to look at?" I'm a mother of a teenage daughter at that point in time. I'm like, "Okay. This is what I'm telling the readers to do. Go in. Go in and look at yourself and find out what's in there, what's driving it, what's that story, what's the pain, and how do you neutralize it? How do you own it again?"

So, as far as a sneak peek, I would say this idea of what's been lost is this beautiful part of you. It's really beautiful and you lost it because you thought it was bad, you really did, or you thought it was going to be painful, or painful for someone you love, and you gotta get it back. And it's really good to get it back.

RX: Yeah. Absolutely. You know, another point that you make in your book that I really connected with is that people who don't feel worthy also struggle with defining what their wants and their needs are. What do you think the connection is between defining your desires and also building a stronger sense of self-worth?

MD: Yeah, that was chronically, has chronically, still is chronically my problem. This idea that you can forget yourself or marginalize your own self. Everybody around me, I could tell you what they wanted. I could tell you what they wanted for dinner, what they wanted to watch on TV, what book they liked, what kind of clothes they liked. And then when it came to me, it's like even asking myself hadn't been seen as valuable, just even the question.

So, that very much comes out of my own personal experience, but also with working with clients over and over and over, "But what do you want?" They have no idea. They have no idea. They know that they're letting down their husband or they know that they're letting down their boss or they know that they're not quite making certain goals that they're hoping for. But they don't know what they want. They don't know what they feel. They haven't really given that question the time and energy and thoughtfulness that it deserves, and it really does deserve to be forefront.

So, throughout The Worthy Mind, I try to bring these questions back. “Who am I? What do I feel? What do I want?” These kind of questions start to sculpt out this idea of self. You can't have self-worth if you don't have a self. So, this brings you back to what does this self feel? What does this self actually want? And to try to neutralize and see desire as a good thing rather than, “Oh, you're just a needy person, and that's bad,” you know? So, I'm trying to flip all these ideas over on their side so that you can just come to a question and just answer it.

RX: So, you mentioned your daughter already. There's this part in your audiobook where you are speaking to your daughter, who was college-aged at the time, and you describe feeling in awe of her self-confidence. And this is a pretty big question, and it's one that I also grapple with, but how can those of us who have had difficult childhoods break the cycle of feeling unworthy for the next generation? And I know you also allude to having a challenging childhood as well.

MD: The biggest difference between she and I [was] that she could own this idea of being angry. This idea of being angry wasn't a bad thing to her and it wasn't overwhelming and it wasn't rage. I think so many of us, if we grew up in abusive households or with neglect or with any kind of dysfunction, like, pretty severe dysfunction, we see anger as very dangerous and we see it as threatening to experience it. Like it could put us in danger or, you know, we saw a mom become unhinged and point their finger in your face or whatever, it scared you as a little kid.

I think that to not have that experience and to see, “Oh, no, anger actually just, you know, [helps define] who I am. I can be angry and it doesn't hurt anybody.” She's not out of control. She's just like, "Nope, that's unfair, period. End of story. And I'm going to fight for myself." Between she and I, those are major differences with us. In general, though, as far as a parent, I will say what made me break the dysfunctional hand-me-downs that I got was having her. I mean, it really did. And I thought I was fine. I really did. I thought, “Oh, my childhood wasn't that bad, and I went to college, I had jobs, I had a house, all the things were fine.” And then I had her and about 18 months in, I'm like, "Oh, I am not fine. Something is radically not okay in me."

And I just knew I needed help and I needed to start really seeking professional help because I was having memories that I didn't remember. And mostly what happened with her was I loved her so much and that contrast is what showed me, “Oh, something wasn't there for me.” Like, I can't imagine doing that to a little kid. I can't imagine saying those words or doing that kind of harm. And so it just woke me up—“Okay, something went wrong and I need to get to the bottom of it, and I definitely need to be aware of it so that I don't repeat it.”

RX: I want to go back to an earlier point you said. I absolutely loved this part of your audiobook where you talked about your daughter owning her anger, and I thought it was such a great point because so many of us struggle with this. Do you have any advice for those of us who do struggle with not allowing ourselves to feel angry?

MD: Yes. One thing would be to rewrite the way you experienced what you called anger. Usually, people that are afraid to feel anger experienced what they're calling anger, and if I can break it down, it actually wasn't anger. So, for instance, if you had a rageful parent or even a rageful teacher that scared you, that wanting to control or dominate a child is not anger. That is actually a form of authoritarianism, that's a form of control, that's fear. And so if you can go back and look at these places where you saw what you called anger, because you were little, and realize, "Oh, this was a person that wanted to dominate me, control me, and terrorize me. That was actually fear. They were afraid, they were afraid of being out of control, powerless, or whatever, and I happened to be a little kid in their way."

That helped me, at least, reframe the idea. Because I didn't want to be the big scary mom. I didn't want to be that person. So, then anger gets buried and I try to be nice all the time. Except that that didn't work either because people take advantage of that. So, you have to have a healthy dose of, "Don't mess with me. I won't mess with you. But I don't need to overpower you. I don't need to scare you."

RX: I can't imagine you ever being the big scary mom.

MD: What my daughter says is when I'm really scary, I'm silent. It's my silent face that scares her [laughs].

RX: Let's talk about this a little bit more. So, how has developing your self-worth affected you as a parent? And you're talking about, it sounds like, striking the right balance between being seen as an authority figure without devolving into this scary parent that's unapproachable.

MD: Worthiness has played into it incredibly powerfully for me. I wanted to be a good mom. And so the feeling of not being a good enough mom was this pain in the center of my parenting for a long time. And I got a divorce. Her life was ruined as she knew it to be up until that point, and it was traumatic for her. It's traumatic for anybody that has to go through a divorce with a child, or just even without children. Divorce is hard. So, if I was always trying to reach this better version of mom, I was always coming from this place of not feeling good enough or strong enough for her.

"When you're living as a fraction of yourself, you're only experiencing a fraction of what you're worth."

And then somewhere around all the inner work that I did that ended up being The Worthy Project book, showed me that I don't have to be a good mom. I can't not be a bad mom. I'm going to be a bad mom and good mom. I'm both. But I am her mom and that's all I am. I want to 100 percent own that I am her mom. And so I thought, “Well, she should know who I am then. She should know that I've made mistakes. She should know what made me go into therapy as a young mom in the first place. She should know that I struggle with certain things, just like she struggles with certain things.” So, in this willingness to be transparent and honest and not have to try to paint myself better than I was, I think she also got permission to show me who she was through that time, and I feel very, very lucky to have had that kind of relationship with her.

RX: Was it challenging for you to open up to her in that way?

MD: By the time that happened I had done a lot of work and I had forgiven myself for mistakes and, for me, it wasn't challenging in the way of, "Oh gosh, this is going to be embarrassing" or "What if this hurts her or alters her?" It's more like, "Will this be of any use? Will knowing me in some way be valuable or not?" And I had to go with maybe it will be. I mean, I wish I had known my mom. I wish I had been able to sit and ask her questions, like, "Why are you doing this?" So, I thought, well, even if I'm not the greatest mom in the world, she should know who I am.

RX: Just speaking as a daughter, I think it is so important to get to know your mom as a person. I feel that your daughter is very lucky that you were able to be vulnerable and open with her in that way. So, now I just want to talk a bit about the recording process. Was there anything during the recording process that surprised you or maybe sparked some new insights?

MD: Well, I can tell you definitely between the two books, one was recorded at the height of COVID, and I live in Big Sur. Now we've got Starlink, so we have actual internet that works, but back then, we did not, and I had to do the entire recording listening on my landline to the people in New York telling me when to start and stop. I definitely was sitting in a room talking about some of the hardest things in my life, and you hear me processing that, for sure, especially in the end of it.

This one was really interesting because it was happening in San Francisco and I had written the book quite a ways before that, and I'd forgotten that I started the book in a certain hotel in San Francisco. So, I had actually woken up that morning from the same hotel where the opening story begins and I had completely forgotten that that's where I was going to start. That was very surreal because I'm sitting there with strangers and I said, "Hang on, hang on, hang on. This is really strange because I forget that I had written this part and I just woke up in this hotel this morning." So, that was really sweet, and the production team was just so kind and so nice and it felt a lot more like, "Oh, right, there's listeners on the other side of this." It didn't feel so alone because somebody would be like, "Oh, that was funny" or "Oh gosh, what happened after that?" You know, when we'd take a break.

And also, I learned that my stomach makes a lot of noises [laughs]. They had to keep pausing the thing because the recording equipment is so intensely good and he's like, "Oh, your stomach's making a noise again." All day long to be told that, I'm like, "Whoa, okay." So, it was nice. How's that sound? This rain is coming in.

RX: Yeah. If you're listening to this interview right now, you may be hearing some ambient rain sounds. Meadow, do you want to tell our listeners why that is and where you're recording from?

MD: So, I live on the side of a mountain, right above the Pacific Ocean in Big Sur, and I live in a yurt. This is what it sounds like when it starts to rain, and it's funny that it started to rain today because that's kind of the kickoff. It's always right after Halloween at some point the rain comes, but it's like within 12 hours today it happened. So, yes, this is my very sweet Big Sur life and I love it. It's very rugged and you're in the elements a lot more.

RX: Well, it's very soothing. I think it goes along with our conversation today. So, back to the audio recording. How do you feel about your listeners receiving your advice and encouragement via audio, maybe versus how they would be receiving it in print or in other forms?

MD: Well, I've gotten lucky because I've been able to publish the paperback version of each book afterwards. So, there will be a paperback after this, but I really almost exclusively hear from my clients that they listen to the audio over and over. I just think that's kind of where we are in life right now. We like to listen, and as a society and humanity, we walk around hearing each other's stories, and I think it feels much more intimate and real to hear it in that way. Working with Audible is very fun because obviously you guys are very good at understanding how to put a story together, and it is different than putting an actual written book together. A written book, people need to be able to find things, so it's formatted differently, and with Audible, the story needs to drive forward. So, that has been fun for me to have to write the two different versions of the same stuff. But for me, I listen to Audible. I listen to everything and then I have the paperback and I'll go back and search it and underline things.

RX: Very cool. So, I have one last question for you, which is what are you looking forward to? Is there a new topic that you'd like to tackle?

MD: Oh, yes. I have a huge book idea. I will say that it is radically meant to change the way that we look at self-care, and it's really coming a little bit off of this worthiness idea. What does self-investment actually look like and how do you care for yourself? What does that actually look like in a relationship, in parenting, in day-to-day living? But I think that's probably all I can say.

RX: Very cool. Well, I feel so fortunate to have heard the topic idea here first, and all of our listeners will just have to stay tuned. So, thank you for speaking with me today, Meadow, and if you're listening in, you can find Meadow DeVor's The Worthy Mind on Audible.

MD: Oh, thank you so much for having me. I really appreciate it.