Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly

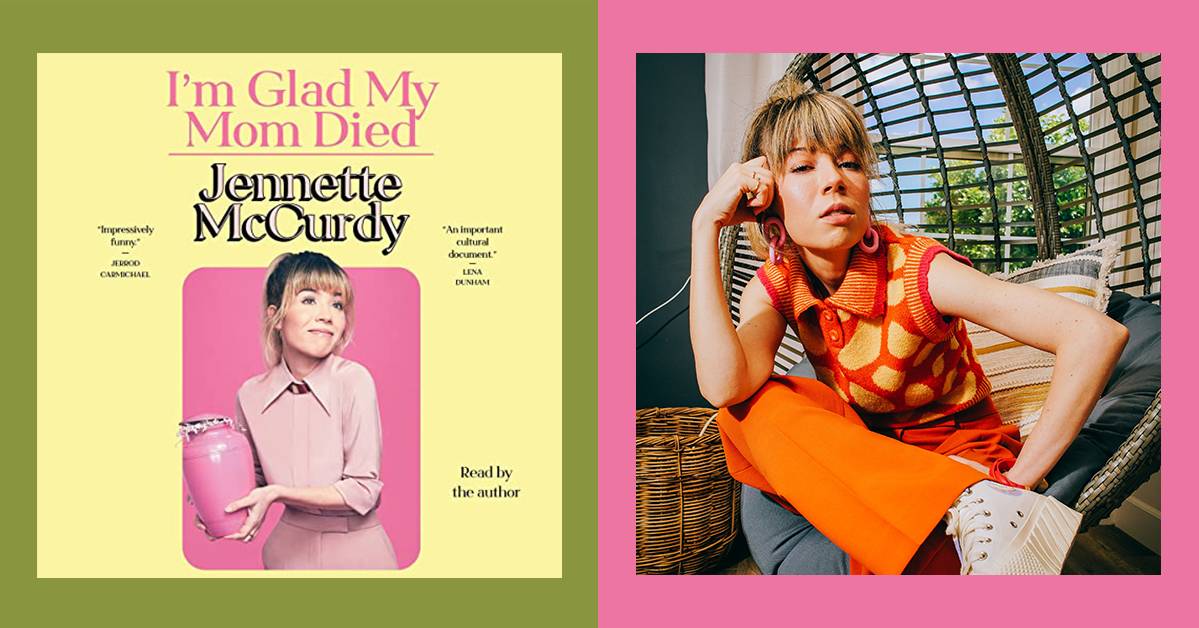

Seth Hartman: Hi listeners, I'm Audible Editor Seth Hartman and with me today is Jennette McCurdy, here to talk about her memoir, I'm Glad My Mom Died. Jennette is an actor, writer, director, and podcaster who broke out initially for her role as Sam on the hit Nickelodeon show iCarly and is now using her platform for self-expression and honest discourse. Jennette, it is such a pleasure to have you with us today.

Jennette McCurdy: It's a pleasure to be here. I appreciate that intro. I like that.

SH: Thanks. So, the tone of this book is so unique. It's vulnerable and funny at the same time, which is really encapsulated in your title. And, of course, that amazing cover with the pink urn. It's just everything. Can you talk to us about your approach to developing this memoir and how you landed on this tone?

JM: Yeah, the tone is something that I'm so glad you mentioned, because it's something that's top of my list for most important aspects of anything that I create. And I feel like anything that's either too serious, without any humor, isn't necessarily truthful, certainly not truthful from my experience. And anything that's just plain humorous, without any of the sort of gravity or the weight of reality, is equally untrue. So, it's so important to me to find that balance of honoring the subject matter that I'm exploring—and sometimes, oftentimes, that gets very heavy—while also finding some levity and some humor in it, because to me that's the most truthful balance. And I think it reflects life, because I've never been in a really serious moment and not had there be some humor, because it's necessary to find that. Otherwise, you're just gonna break down crying. And likewise, I've never been in a just absurdly humorous situation without there being some tragedy that's sort of underpinning it all. So, that was very important to me, but I think that piece is just sort of more of who I am or maybe my voice or my perspective on things.

SH: Right. Your voice and your attitude really brought so much to it. That's actually what I wanted to ask you next. This audiobook is brought to life by this incredibly honest, visceral, real performance from you. What was it like recording your own words like that, and how did it differ from maybe doing your play?

JM: I was a little nervous the morning of. I didn't have any nerves built up. I felt like, “Okay, I'm a pretty solid reader, and then reading my own words that I wrote should be even easier, right? This should be fine.” And then the morning comes and I suddenly was like, “Why am I wanting to read this as a different person, you know, more performatively?” And then on the drive over, I really tried to just ground myself and remind myself that just being present—present with the material, I think, was the most important piece, so that I could just let it sort of speak through me. It's so different to me, the writing process versus any sort of performing process.

I will say, there was something very healing about the recording of this audiobook for me in terms of my relationship with performing. I didn't expect that at all, and I've only recently started connecting some of these dots. But I recorded it a couple of months back, and shortly after I finished, I started having thoughts where I was entertaining acting in some way in my future. And I'd always—it was very important for me a couple of years back, I guess, oh my God, a long time ago now, maybe six years ago, I did a hard walk away from acting. I said, "This is no longer for me. It doesn't serve me anymore. And it's, if anything, really detrimental to my mental health, and I need my own identity away from this career and the baggage that came with it for me."

"There was something very healing about the recording of this audiobook for me in terms of my relationship with performing."

But I felt for the first time, and I think it was largely because of recording the audiobook, that there might be a way for me to act again, in a way that's healing and doesn't carry the baggage from the past. And it was surprising. I mean, shocking. I really, really thought, “I'm never going anywhere near that again, that's a hard line for me.” And then I felt this kind of openness, and I think it might have come from how healing the process was for me doing the audiobook and feeling like I enjoyed it. I had fun. Like, that hadn't happened for me before with performing. And then I'm able to perform this book that means so much to me, and perform it in the way that I want to, and it felt like I had that—I felt empowered with acting instead of like a puppet doing it. Instead of completely controlled by the external forces around me and everybody's feedback weighing in, I felt like, “Wow, this is really—this is that connection that I never felt before with acting.” And I appreciated that I suddenly had this openness toward it.

SH: That's amazing. That really warms my heart to hear, because I know how fraught your relationship with acting is, and how it obviously connects to your mom and all of this stuff with feeling so responsible for your family back when you were young. So that's really great to hear. I, of course, want to talk about your mom. Much of this title is about your relationship with your mom, and for me, one scene that really stood out as kind of a microcosm of your relationship is that great ice cream shop scene. I'd like to play a clip. Here it is.

"That’s right. My baby’s funny. And serious too, when she needs to be. She’s got it all. You want Nutty Coconut?"

"Um, no, I think I’ll do Cookies N’ Cream."

Mom turns to me, alarmed. "You don’t want Nutty Coconut?"

I’m frozen. I don’t know what to say. Mom seems upset that I haven’t chosen Nutty Coconut. I pause, waiting a beat to see how she reacts before making my next move. There’s a beat where we’re both just standing at the ice cream counter looking at each other instead of at the ice cream.

Then Mom’s posture softens and her eyes well with tears. "Nutty Coconut’s been your favorite for eight months. You’re changing. Growing up."

I take her hand in mine. "Never mind. I want Nutty Coconut."

SH: So, first of all, that's just to me such a powerful moment, and it kind of works to me as a microcosm of your relationship, mostly because it seems like even at such a young age you were so hyperconscious of your mom's feelings. Do you think that's an accurate assessment there?

JM: One million percent. Yes, I was hypervigilant to her every flinch and really tuned in to her emotions and her desires and her needs to the point that I had really struggled to access my own.

SH: Yeah, and obviously this is just about ice cream, but so many points throughout the book, it seems like you're thinking about going right and then you hear your mom's voice—either directly or just from so much repetition, what your mom is going to expect—kind of telling you to go left. And how could you not go left when this person has so much power in your life? That moment really locked that idea in.

So, pivoting away from your audiobook for a bit, I want to talk about your podcasting work. In preparation, I was listening to Empty Inside a bunch, and you've had so many great guests. It's such a good podcast. So much vulnerability and honesty, it's awesome. I wanted to go to an episode that you had with Leah Waters, when you were talking about mothers, and abusive relationships in general. During the conversation, she brought up a quote that seemed to resonate a lot with the both of you. She said, in reference to her own mother, "That's not actually care, that's manipulation. That's not actually love, that's abuse." So, when you're in a relationship like that, it can be really hard to differentiate those concepts. What do you think the point was that you finally saw that difference with your own relationship with your mom?

JM: Wow, I really appreciate that question. It took so long for me because even after she died, I was still determined to keep her on the pedestal that I'd had her on. And even when I initially went to therapy and my therapist had suggested "Hey, the things that you're describing are abuse, like, your mother was abusive," I couldn't hear it. And I describe this in the book, but I stopped therapy because I couldn't tolerate the potential reality that my mother was abusive, because that would mean reframing every single thing about my world. My world was, from such an early age, oriented around this narrative that my mom knows what's best for me. My mom wants what's best for me. I don't know how to do anything myself. I'm incapable and incompetent, but mom knows, and without mom I'm nothing. And even though she's gone now, I need to continue living out whatever her hopes and dreams were for me and just hope and pray that I can live out her intentions for me.

"My world was, from such an early age, oriented around this narrative that my mom knows what's best for me."

And it wasn't until several years later, when I went into therapy again, that I was able to really face the reality of our relationship and the abusive nature of it. I mean, I was definitely in my twenties. I was in probably my early twenties still at that point. But it was the hardest personal work I've ever done. It was really hard to face, and I would say it also came in pieces. It wasn't like I immediately, you know, went from, “Oh, she's this perfect angel and she wanted everything that was best for me and she could do no wrong” to then the next day, “I'm glad she died.” Like, that wasn't my process. It really took years of coming to terms with the reality of my childhood and my adolescence and my young adulthood to accept the reality, which was, as I see it now, that she was abusive and manipulative and overwhelmingly narcissistic and that I am glad that she died, very, you know, honestly.

SH: That's all really powerful stuff. I remember that section from the book when you were framing these things to your therapist in the first place. You were referencing how your mom essentially taught you an eating disorder and I remember you kept saying that she helped you out, which I thought that transition from the frame of reference was so incredible in that moment.

JM: Hmm.

SH: So, as a young person, as an actor, you were forced to support your family both financially and emotionally. You were quoted on an episode of The Minimalists Podcast saying, "I don't think young people should be allowed to be famous." Do you think that a healthy model for child stardom exists? Or do you think it's an inherently problematic system?

JM: I really believe it's an inherently problematic system. I feel very strongly about that. I think that even with the best support system around you, even let's just say, you know, some kid has massive amounts of success and they have wonderful parents who just support—if it was their child's dream, they're just supporting their child's dream. And they have managers and agents and they somehow work with every studio that just totally respects that they're a child and honors them as a child. I just think that's a fantasy. I don't think it's possible to get in the entertainment industry at an early age and remain unscathed by young adulthood.

And I also think there's this thing that happens where when you get really known in the public eye, it stunts you. I think it really stunts you, because that's not reality. Being famous and being recognized wherever you go is not reality. It's this weird alternate reality and I think you suddenly orient to this thing that is not real. And then understanding that it's not real, that it's just an experience specific to you or, in my case, specific to me, unpacking that and figuring out what is actually reality, was very difficult. It was very difficult and I can't imagine there being a set of circumstances where it's not, at the very least, very difficult for somebody. Although, I absolutely applaud and admire people who come out from the other end of it intact, and with dignity and grace. And I think there are quite a few examples of that, but I don't think they got there without a lot of hard work.

SH: Right. And you mentioned multiple times throughout the book how difficult it can be for child actors to make it through and transition to successful careers, or even just have a kind of intact mental state at the end. Even that would be an incredible mountain to climb.

JM: Yeah.

SH: I wanted to ask you, in today's world it seems like public discourse seems to really prioritize empathy and mental health, at least on the surface. Do you think that this sort of brave new world of mental health and self-care applies to child actors, or do you think it's as bad as it used to be and people are kind of looking for these successful young kids to fail?

JM: Oh, my God. What a juicy one. I really appreciate your caveat of “at least on the surface.” Even if this mental health awareness kind of movement is a bit zeitgeisty and a bit buzzy and will kind of wane at some point, I think there's no way for it to be this potent and not have some lasting effect. And I think that's incredible and very promising. And I do think that this applies to young people. I think even conversations around oversexualizing young female performers are happening, and I know that wasn't happening a decade ago even. So, I think there's a lot of positive movement happening, and I think it's very encouraging and I do feel a bit optimistic about it.

SH: Hmm.

JM: Cautiously optimistic.

SH: That's great. So, I wanted to lob one to our listeners who might not know your more recent work and are more familiar with your work on Nickelodeon from iCarly or Sam & Cat. You've been very public about how you've walked away from acting. And I'm sure many of our listeners know that there was a recent reboot of iCarly that you decided not to participate in. You seem very resolute in this decision in the audiobook, but I was wondering if part of you was worried about your public image and if you were disappointing anyone through that decision?

JM: No, I wasn't concerned about turning down the reboot because I know that it was a decision I needed to make for my mental health, and I feel like [that] can just be this umbrella term that almost sounds like an excuse or something, but for me, I knew that the risk of—I consider myself recovered in terms of eating disorders and I really carry pride about that. I didn't want to be at risk for that. I didn't want to be at risk for anxiety and depression, which I knew would come on strong if I did the reboot. And I also knew it would bring me shame, and I think shame really does play a part in mental health struggles, and it was just a very simple decision for me.

And I also trusted that the people who support me now, it's a different type of person. It's just a completely different reaction when people come up to me on the street and say, "Oh, my God, I listen to your podcast." Sometimes they're crying, sometimes they'll tell me aspects of their life, and there's this connection that was not there before when people would just scream, "Hey Sam, where's the fried chicken?" I felt like there was no human-to-human interaction and now I feel like there is a deeply human-to-human interaction with the people that approach me now, so I wasn't so concerned if somebody was upset about me not doing the reboot. That's absolutely their right and I wish them well on their path, but we're just on different paths, we're doing different things.

SH: As somebody who kind of sees himself as a bit of a people-pleaser, that section was really powerful to me. Because you've been doing work for other people your entire life, and that was really a great example of you taking a stand, even to someone who you care about, like Miranda [Cosgrove], so I applaud you for that decision. I think that was one of the most powerful moments of the book for me. I think that was very brave of you, even if you just see it as something you were doing for yourself. I think that's a lesson that other people could really learn, so I thought that was a very powerful section.

JM: Thank you so much, I really appreciate that.

SH: I want to talk about how open and vulnerable you were throughout this entire book. You know, it was such a baring of one's soul. I've honestly never heard such an open and honest discussion about eating disorders, specifically. Even today, this kind of stuff can be really taboo for some people. So, how were you able to put yourself in a headspace that you could be so open about it? And how did you take care of yourself while revisiting these really dark moments in your life without overwhelming yourself?

JM: At the point when I started writing the book, I had been in therapy for seven years. I'd worked with an eating disorder specialist initially, after that first therapist that I mentioned earlier that I left after she said, "Hey, your mom was abusive.” I eventually saw an eating disorder specialist to kind of kick the eating disorder first, and then I saw just a conventional sort of CBT therapist who I still see now. Hello, Erin. She's a lovely, beautiful angel who's helped me so much. I'm so grateful to her for everything.

I had been in therapy for so long and had processed so much of my past. I, in no way, would have gone near writing this book or exploring any of this in a public-facing or creative way—even if the creativity was not public-facing, I wouldn't have gone anywhere near it—had I not done so much processing on my own. Because I think that would have been a detriment to my own growth and also to anyone who would potentially have read anything or seen anything. I think that would have just been doing a disservice to everyone if I'm trying to find my own way and haven't really developed a perspective on it and if I'd still been struggling with an eating disorder. Like, the chaos would have been reflected and, in some way, maybe even a little contagious. So, I definitely felt like I did a lot of that work and processing ahead of going anywhere near writing about it, and I did feel really ready and really sound by the time I eventually sat down at the computer to start writing.

SH: I applaud you on doing such great work on yourself. It's very evident and I just couldn't believe how honest it was, you know? I would be absolutely terrified to bare my soul like that, and I just think it's so gutsy. I wanted to talk about how you've become an outspoken advocate for abuse victims and people suffering from mental health issues, and eating disorders, specifically. Can you tell me about what it feels like to do advocacy work and the kind of relationships you've had with people who've dealt with similar issues to yourself?

JM: It initially started with anger for me. I remember once I worked through a lot of the shame that I had built up toward eating disorders, once I started kind of clawing my way out of them and into recovery, I then felt this anger that I didn't think they were talked about enough, openly enough, frankly enough. Also, I felt like with eating disorders, specifically, they're always talked about in such a hopeless way. That made me angry. And I wanted to channel that anger into something, because—I learned this in therapy—but anger is a really motivating emotion and it's just a matter of finding the right vehicle for it. And I had really struggled with that a lot in my past. But speaking out felt to me like a way of channeling the anger and using it in some way for good and for connection and for, hopefully, help and healing, and with others.

But it was also really scary. I remember the first time—I'd written an article, and Huffington Post was going to publish it, and I remember feeling scared the night before it got published because I thought, “Oh well, there's no turning back now. I'm owning this. I'm being accountable.” And there's something about that public accountability that was definitely scary, but I absolutely stand by that decision and see it as being really good and important for my own growth, and hopefully for others. And I will say, now a lot of the people who approach me are people who struggle with eating disorders and say, like, "Oh my God, this episode of your podcast really helped me to find a therapist that I connected with or really motivated me to pick up a book that I hadn't done."

And hearing people’s recovery stories that are in any way connected to my sharing or advocacy is the most fulfilling thing, like there's nothing to compare it to. It just feels like, “Oh, my God, it makes it all feel like it was worth something.” And I think there's that deep need underneath it to find some worth, because otherwise it's just like, “Well, that was just hell for a dozen years.” Like, it can't have been that, right? It had to be for something, so that connection piece definitely makes it feel worthwhile and feel like it was for something.

"A lot of the people who approach me are people who struggle with eating disorders... And hearing people’s recovery stories that are in any way connected to my sharing or advocacy is the most fulfilling thing."

SH: That's amazing, and what a story. What a journey, to have come from people running up to you on the street and yelling, like, "Butter sock girl," to now people are coming up to you and saying that you helped make their lives better. That's about as fulfilling as I can imagine, so that must feel really great when that happens.

JM: Oh, night and day, yeah. You hit the nail on the head. It was, "Hey Sam, where's the butter sock?" Or then, "Hey Sam, you eat any fried chicken lately?" And they always did it in a coy way, like, “I'm being so clever” [laughs].

SH: Yeah, like “I'm the first person who came up with that joke.” [Laughs]

JM: Yeah, exactly.

SH: Ugh. That's, like, the most low-hanging fruit. At least come up with a deep cut, you know.

JM: [Laughs] Thank you, I appreciate that. And then there was also a part of me that at the time when I was struggling would wanna be like, "No, I actually didn't enjoy the fried chicken because I was throwing up the fried chicken because I had bulimia." But I of course didn't blow down the house of cards in those moments. But I had the urge sometimes. I definitely had the urge.

SH: That irony was definitely very present for me. So, let me take this opportunity to ask what's next for you, Jennette?

JM: I'm doing more writing. I'm working on a novel and I'm working on a collection of essays. I sort of initially started working on the collection of essays and got about halfway through that and then just felt compelled to start this novel. And so it's been a really unique and fulfilling process because I've avoided getting burned out on either one, and that can definitely happen for me where—I'm sure you relate to this—but just getting deep into a project and being like, “Oh my God, I'm so burned out but I gotta keep plugging away because I gotta keep doing this thing.” And it's been really nice to be able to switch gears if I'm feeling like, “Oh, I'm starting to feel it. I'm starting to feel the itch to move on.” I can go switch from the essays to the novel, and vice versa, so that's been very nice. And also, as for the novel, it's really nice to write something that's not personal. It feels really new and exciting for me.

SH: That's amazing. Could you say that it feels novel?

JM: [Laughs.]

SH: Right, that was terrible [laughs]. I had to.

JM: I’m glad you did. This was so fun. Thank you so much. I really, really enjoyed this a lot.

SH: This was an absolute pleasure. And listeners, you can find I'm Glad My Mom Died by Jennette McCurdy on Audible now.