Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

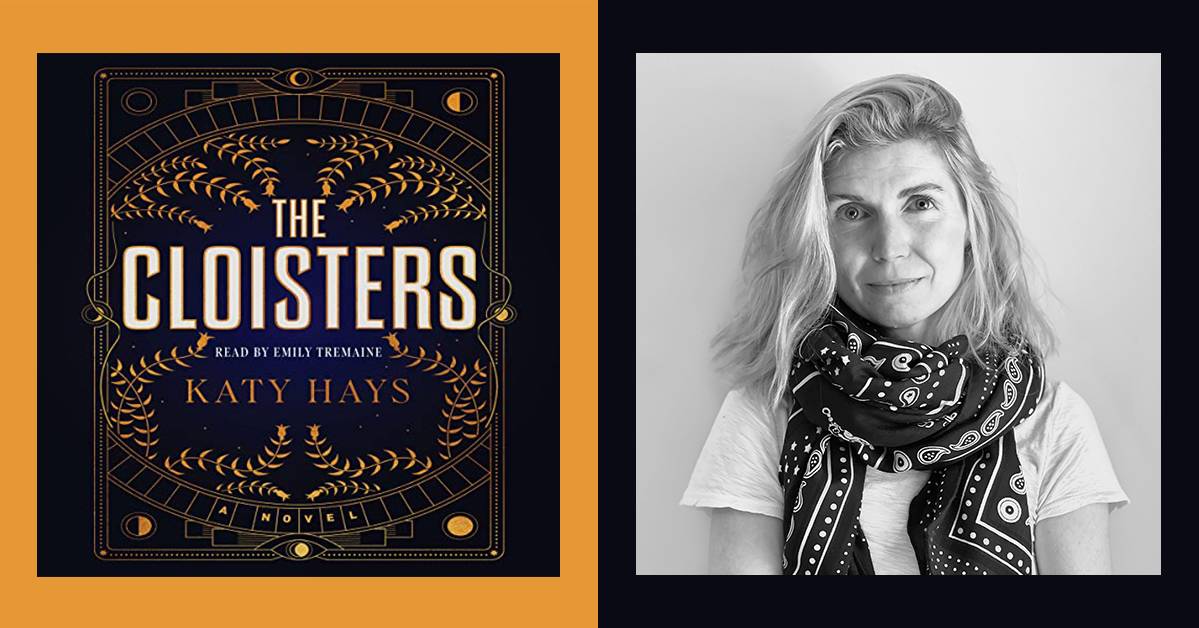

Haley Hill: Hello, I'm Audible Editor Haley Hill, and today I'm so excited to speak with author Katy Hays about her enchanting debut novel, The Cloisters. Set in the renowned Gothic gardens, after which it is named, of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s medieval branch, this captivating story unfolds over one sinister summer when an aspiring group of researchers uncover a mysterious deck of tarot cards that just might contain the scripts of fate and fortune themselves. Welcome, Katy, and thank you for being here today.

Katy Hays: Thanks so much, Haley. It's a pleasure to speak with you.

HH: Oh, of course. So, to begin, I'd love to learn about how you started working on The Cloisters. It is no surprise that in addition to being a talented writer, you're an art history adjunct professor. Your deep knowledge of medieval art and Gothic aesthetics just really shines through in your attention to details in this story. So, I was curious, when did you first decide to realize your path as a fiction writer? And what was it that prompted you to write this particular story as your debut fiction novel? Was it a particular research topic or conversation in your academic life that inspired you?

KH: You know, it's a great question and I think for me, actually, as a writer, I'm really interested in the question of “What are we capable of believing in?” And so I came to this book from that perspective, kind of asking myself, whether it's a charismatic con man or a cult or tarot or astrology or manifesting or fringe religions, I'm really interested in the question of what humans are capable of believing. And so that's really how I came to this book. I was interested in that as a core question, and tarot, to me, seems like a really interesting way to explore that.

Naturally, I do come with an academic background in art history. The great irony to me, of course, is that I am not a medievalist. I actually worked primarily in modern art history. So, for me, medieval art history was new material in a lot of ways. Not new in that I had never encountered it before, but new in that it wasn't, for me, a place that I felt as comfortable as modernism. So, I kind of started researching tarot cards and was really interested in their early history, from the 15th century, primarily. And the kind of strands came together: the Cloisters as an incredible location, the idea that tarot was actually this really early card game, and my interest in the question of “What can we convince ourselves of?” They all came together at the same time.

HH: I really want to learn more about your relationship to tarot and future-telling, but I'm also curious, I actually went to the Cloisters for the first time this weekend, to prep for this interview. And I'm just so fascinated to learn that you researched the Middle Ages for this story, rather than being a Middle Age specialist. It's so interesting to learn that the Cloisters is really America's only museum dedicated to the art and architecture of the Middle Ages, and it just really stands apart from the rest of the Met and the rest of New York City itself. Just going there, it feels like a cloister in its own way. It's above the Hudson. It's just this incredible, mystical-feeling place. What initially inspired you to set your story at this one-of-a-kind museum?

KH: I have to say, I hope if people get one thing out of reading this novel, it's a desire to visit the museum itself, because I think it is such a gem. Like you said, Haley, it's at the very northern tip of Manhattan. It feels a world away from the city. It is this incredible 12th-century monastery, rebuilt by hand. And for me, I have to say as a reader, I love to read a book that takes me someplace new or someplace that I want to spend six to 10 hours. And growing up, I grew up in a rural part of the southern Bay Area. When I was a kid, we didn't have TV; there was no cable in our house. My parents were very anti-television. My mom had this great bumper sticker on her really old diesel Volvo station wagon that said, "Kill Your TV."

And both of my parents are really big readers, and so I grew up, basically, traveling through books. And I think a lot of readers and writers do. And for me, I always want to set my book in a place that someone wants to really feel immersed in the atmosphere, in the environment. And so the Cloisters felt like this incredible setting for a novel. In some ways, it also felt like low-hanging fruit because I hadn't ever come across a novel that was set there. I mean, please, someone tell me if you find one. I still haven't. But museums are such popular places for fiction that the Cloisters really felt like this wonderful, unique setting. And I was thinking about it and working on it during the pandemic when still we weren't able to travel very much, and it gave me an opportunity to spend some time in my own head, in the imaginative world of the Cloisters, when we were so shut-down and limited.

"I want people to take away from this book and from the Cloisters that the medieval period isn't just a period of darkness and a turning away from the classical period, but is in fact this gorgeous, rich, incredibly unusual time period."

And so, I think for me, that's really why I gravitated to it as a setting. I was so interested in tarot and, interestingly, two of the most complete tarot decks from the 15th century are held on the East Coast. One's at Yale, at the Beinecke, and the other one is actually at the Morgan, not at the Cloisters. But the Cloisters does have individual tarot cards in their collection. And years ago, I think it was 2016 maybe, I went to an exhibition at the Cloisters called, “The World in Play,” which was about early playing cards. And they had some tarot card examples there as well. And I think that was also something I was thinking about. I've obviously been to the Cloisters and have enjoyed it as a museum, and the world felt so rich and ready for some disruptive characters.

HH: I love that. It's interesting to me that you're writing it from this place of isolation and also sort of creating this setting, which truly is just so atmospheric. I feel like that just shines so much. Apart from the plot and everything else, you really do submerge your listeners in this space. As an art historian and, again, now learning that you are new to medievalism as well, what facts surprised you the most during your time spent working on The Cloisters?

KH: I am lucky to have some good friends who are medievalists, and I have been lucky to be able to sit in on some great medieval seminars. So, I'm not coming to medievalism completely bereft of information, luckily, but I do not consider myself an expert, at all. And I'm sure the curators at the Cloisters are horrified by the fact that I had to move the location of the library for fictional purposes in the novel. But I think one of the things that people often think about when we think about the medieval period and when we think about the Middle Ages, we see it as this incredibly dark and really Gothic and kind of hard-edged environment. I think sometimes the world or the atmosphere of Game of Thrones, where everything is shot with a gray lens, is what we often think of.

But one of the things that I feel like the Cloisters really brings home, the location, and that I hope the novel brings home, is that, in addition to having this traditionally Gothic vibe, the Middle Ages also was a time period of incredible beauty and complexity. I mean, the Cloisters itself is full of these incredible jewel box reliquaries and these massive tapestries that are so intricately woven with these just absolutely magical unicorns. I mean, really, I want people to take away from this book and from the Cloisters that the medieval period isn't just a period of darkness and a turning away from the classical period, but is in fact this gorgeous, rich, incredibly unusual time period. And I think in a lot of ways that really lends itself beautifully to fiction, because as a time period it is so rich with weirdness.

I mean, you talk about the marginalia, I think one of my favorite things about the medieval period are the fact that there are all these weird doodles in the margins of a lot of illuminated manuscripts. Sometimes there are little animals, sometimes there are people, and I just think that there's such a delight in the kind of unusual and the uncanny in the medieval period that should be more celebrated and that people should see more of. And so that was something I was really interested in bringing out, not only this kind of creepy and Gothic vibe but also this kind of delicate, beautiful, golden, vibrant medieval period.

HH: I really love how your imagery itself can turn the visual world into a work of art. I wanted to ask a couple questions about how you treat both mediums as someone who works with art history. Throughout, I was thinking about that Art History 101 lesson that says, you know, "Describe the details in this very fine-tuned way." And then you can read into them but you can't necessarily say, "The painting shows this person feeling this way." It's more, “The painting shows this person and the smile on their face suggests that they may feel this way.” You know, you have to describe each detail. How has your background in describing art influenced your ability to craft such an atmospheric, enchanting setting? I was just curious about what you prioritized when translating a work of art, as in an icon or something within the Cloisters—an artifact—into prose.

KH: You know, I think it's funny because you also asked me earlier how I came to fiction writing. And I think the reality is, a lot of academics, especially in the humanities, I should say, all we know how to do is write and research and teach. That's the bread-and-butter of the work we're doing. And I think a lot of academic writing gets a bad rap because it's often seen as very dry and very difficult to get through. But I have actually been lucky in my academic career to know and to work with some writers and researchers and scholars whose writing is, I think, so incredible and really beautiful nonfiction writing. And I think that there are some art historians out there whose skill at describing art work is just, I mean, quite frankly, unparalleled and that I couldn't even come close to.

And so I think there's so much already in the humanities that sets you up for fiction writing in an interesting way. Obviously, we're very used to using words and I think that, for me, when it comes to looking at art objects and translating those into writing, certainly that's something that having an academic background in the arts helps you with. I've spent a lot of time also working with students around that and how they can start to see what they see in an artwork.

But as far as what I prioritize, I want the thing that's going to sing the most for the reader. As much as there are a lot of similarities between academic work and fiction writing, the reality is, what I would write were I writing for a textbook chapter or a lecture is completely different than what I'm writing for the reader of The Cloisters, the novel. Because I want people to feel that immediate visceral response when you look at something. So, if you're looking at an icon, the thing you notice the most is the way that gold glitters. If you're looking at a statue, sometimes what you notice most is how weirdly elongated they are. If you're walking underneath a series of archways, you're probably noticing the tops of the capitals and the way they're decorated. And so, for me, there's a huge spectrum here. And in fiction writing, I feel like I go more for what will be emotive and evocative. Whereas in an academic example, I might go for something a little bit drier, certainly something more complete than what I'm offering in The Cloisters.

But I think that one of the things that you do learn working a lot with art objects is just how much time you can get from a reader before they become bored reading about an object, right? So, when you go to a museum, a wall label is only, like, 150 words, as opposed to a 1,500-word essay on the wall next to the art object. And so I'm always also looking for a way to encapsulate the object or the space that feels concise but really deeply evocative.

HH: I so agree that there is an emotional and evocative space to academia that I think is not the immediate assumption that people think of or what they relate to their idea of academic writing, which is dry and stuffy. And I think you bring this point across so brilliantly with your protagonist, Ann Stillwell, so I'd love to talk about her for a little bit. She, herself, is a passionate researcher, and you being a professor yourself, writing about academia and what drives academics in their pursuit of knowledge, feels a bit meta to me, but I don't want to assume. I would love to know how you feel about the value of finding yourself through academic research and studying something you love.

KH: It's an interesting question, and I should say there are a lot of things Ann and I might share, but there are a lot of things we don't share. I, as an adjunct professor, have in a lot of ways kind of opted out of that full, obsessive academic lifestyle. I decided when I was at Berkeley that I didn't want to finish my PhD. I wanted to choose where I was going to live. I wanted to be able to stay in the state that I loved and be close to family. And I knew that if I finished and went on a tenure track job search, I would probably end up having to move to, like, Iowa, for example. Nothing wrong with Iowa, but my family is all here. I wanted to stay in California. And I think Ann is still in the throes of that early kind of flush of excitement and enthusiasm with this scholarship and with academia.

And I think that academia is one of those things that lends itself so beautifully to fiction because it's really this kind of closed world. It's this environment in which we make our own rules. It’s an environment that really rewards the total subjugation of the self to something larger. You get to kind of feel virtuous because it's in pursuit of something bigger, in pursuit of this research. You're being kind of supported by your cohort around you, your peers. You're also being cheered on by a mentor. And I think that kind of environment and that world just lends itself so beautifully to a fictional academic setting. And so I think one of the things I really enjoyed writing Ann, is that she's still so enthusiastic and kind of green on the scene about wanting to get involved in this and what she's willing to sacrifice and give up for it.

In a lot of ways, that is a result of her youth and her naivete, as somebody, personally, on the backside of it all. So I think that's something that I was really interested in. And of course, I'm always interested in what happens when somebody who isn't familiar with this world basically gets dropped into it. What does it look like when you come from a place like Walla Walla? Which I should say I feel like gets a bad rap in the book but is an incredible town. I just needed a small liberal arts college on the West Coast, basically. But I think there's a huge gap between a place like Walla Walla, and even Whitman, which is a great and incredible school, and going to work at the Met and transitioning to a larger university or intellectual and academic sphere.

HH: Yeah, I totally relate to that. Before I came to Audible, I always thought I wanted to go into academia myself. I really wanted to get my English PhD. And then I realized that what it was about for me was actually I needed a space where I could be prompted to read stories and learn about things and talk about it because I felt like it helped me realize my emotions about myself and grow. And it might not be about the topic at all. But just that type of critical thinking and analysis, I think, is really helpful, and I love that about Ann.

It's fantastic following her, because I suppose I haven't mentioned yet to the listeners that this story is, at its core, a mystery as well. And I loved listening to Ann use these research skills and just her sharp knowledge to follow and decode the clues, especially since she is very skilled in translation. I think that lends to the coding. But I do also love that she can leave the Cloisters and go to upstate New York and it's still this experience that is part of her program even though it's external to the program. But it's a part of her summer and her growth and you see her grow in these other spaces. I think that just sort of reflects the fact that perhaps what draws people to academia is more the drive to be constantly learning and not necessarily about a topic. Did you find that you learned anything about yourself while writing this novel?

KH: I'm not sure I learned anything about myself, necessarily, while writing this novel. I find writing every novel to be a really different experience and each book seems to have its own set of challenges. What I do think I learned is that I am more able to push through than I thought I was. I think that one of the things that's really hard about just writing in general is that you are always, especially if you're, like me, a debut author, you're always balancing your life obligations and your real, full-time job with the demands of finishing a novel. I think there were definitely moments writing this book that I was very tired, balancing a teaching load, and I'm married. You've got houses and lives and friends and dogs and work, and then also trying to write a book is often a really big ask. And so I think one of the things I learned about myself was actually that I felt like I had a lot more perseverance when it came to fiction than when it came to academia.

"I think that academia is one of those things that lends itself so beautifully to fiction because it's really this kind of closed world. It's this environment in which we make our own rules. It’s an environment that really rewards the total subjugation of the self to something larger."

HH: I personally think that's a very valuable lesson to take away from it. This is an incredible work of fiction. I think that it's something to be very proud of.

KH: One of the things that I find really funny about this book, too, is that it's a book, in a lot of ways, obviously, it's about fate. But the flip side of fate, I feel like, is often chance or luck. And I think that one of the really ironic things to me is that I've written this book that largely deals with the question of “How much of our life is up to us to decide and how much of it is just waiting for us? How much of it is predestined?” And I think one of the things that's really funny throughout this process has been that I feel like this book has been very lucky. I mean, obviously, it's lucky that I'm getting to speak with you today. I feel like it's really lucky that it found the right editor. I think it's lucky that it found the right imprint. You had mentioned earlier that in some ways the book felt very meta with my own academic background. But to me, I feel like the book is actually very meta around the good fortune the book has had and this question of luck and chance and fate.

HH: Exactly. That is what I hoped to get into about the tarot and future-telling. I was really curious what your relationship was to tarot and future-telling prior to coming into working on your debut novel. And how much has it transformed throughout the process, if it has at all?

KH: It's an incredible question and I think, for me, it's a really complicated question, because I am very much, at my core, a deeply rational person. I am the sort of person who doesn't believe in manifesting, doesn't believe in astrology, doesn't believe in things like tarot, doesn't believe in you name whatever new age and/or deeply old tradition there is. But there is also a side of me that is deeply curious and always asking the question, “What if this were true?” So, what if astrology were true? What if manifesting were true? What would that look like? What does that mean? What does that mean about my life, about your life, about the choices we're making? And I think I am always really mindful of wanting to allow for the fact that I think there are things in this world we can't explain.

So, I think I want to allow for a world in which tarot is a form of divination, where astrology does say something deep and authentic about yourself, where, you know, potentially you could manifest something. I want to believe in a world where that's possible. But I think the rational side of me really fights with that and says, "You know that's not true. How could that be possible?" And so this, for me, I think in writing this book, I was also really working out these ideas and the tension I feel within myself around these two things: my desire, almost desperately, to believe the divinatory practices might be real, that tarot and astrology have very real bearings on our future, versus my hesitation around all of that.

And also the fear around what all of that means, right? Because if we're saying, "Oh, this deck of cards could tell the future" or "Oh, your birth chart and where the planets were arranged when you were born can say something about not just who you are but what's waiting for you," I think that’s also, on some level, really scary. And I think if you really get into what that says about how little control we have in our lives—I don't know, for me, I'm always working through these questions. Like I said at the top of our interview, I am really fascinated in this question of what are we capable of believing. Why do we want to believe it? This book was, in a lot of ways, me teasing out these questions, even more so, I think, than the art historical aspect of it. I was really rooted in these core questions around fate, divination, what we want to believe, what we might want to know, and what we don't want to know.

HH: Totally. And I think that's so cool that you were saying that going through the writing process challenged you to think about fate and choice and realization. I think your novel also points to this—how so much of it is written and scripted and what's written in the cards and how will that come true. I think it's interesting to think about you putting words on paper to realize the story that you feel is in the cards for you to complete, and now you have to realize that, in a way. I think [it’s] a really interesting meta experience.

And then, to talk about scripts, there's one question at the beginning of The Cloisters that I think might be a challenge, perhaps, to answer. And maybe that is what drove you, is this challenge. I have no clue how I would answer, but I was curious if you had any idea? The quote in question is, "What if our whole life, how we live and die, has already been decided for us? Would you want to know if a roll of a dice or a deal of the cards could tell you the outcome?"

KH: You know, I would say I don't want to know. And I think that one of the things that's hard, you know, you asked earlier about my personal experience with tarot, and the truth is, I obviously own a deck of tarot cards. I've used them and I find myself so easily scared by what I can pull out of a deck of tarot cards that I will often just not use them because I'm so easily creeped. As much as I say I'm deeply rational and I don't believe these things, I'm so easily scared that I can be certain in saying I would not want to know, at all, if a deck of cards or a roll of the dice could tell us the outcome of our lives. I do not want to know.

"I was also really working out these ideas and the tension I feel within myself around these two things: my desire, almost desperately, to believe the divinatory practices might be real, that tarot and astrology have very real bearings on our future, versus my hesitation around all of that."

But it's definitely one of those questions that I think has plagued people since the ancient Greek and Roman times. I mean, what we're talking about are not new questions. I think at their core, these are really old questions that have preoccupied not just philosophers but everyday people for centuries. One of the things I enjoyed so much about The Cloisters, too, was the ability to talk a little bit about astrology during the Renaissance and how much rich Renaissance Italians believed in astrology. I feel like there are so many things that have persisted over time, that these are really old questions. And they're also old techniques that we're grappling with.

HH: Yeah, I love the way that myths create character. I'm personally really interested in the story of Adam and Eve, which plays out a few times throughout [The Cloisters], just that idea of, like, "Would you have bitten the apple, had you not been scripted to do so, out of your own free will?" I love the way, too, that you can see a tarot card and it's supposed to resonate with these personality traits and characteristics. And I really love the way that The Cloisters plays with these characters and it's sort of this will they, won't they fulfill that assumption that you might be gathering from them through the cards that they draw or maybe their relationship to being a snake in a garden or something like that, you know?

KH: I think that's really true. I think it's a book but it's also a place. And it's a style of art that is so steeped in symbolism. You talked a little bit about Adam and Eve, the question of snakes in the garden. I think there's so much symbolism in this book that actually came to it really naturally, and it was not crammed into it in any kind of conscious way. But talking about it, it's really interesting to me how much it reveals itself to already be there.

HH: Speaking about revealing itself to come to fruition, I was also curious about your process casting your narrator, Emily Tremaine, who does such a fantastic job. What was the casting process like and what were you looking for in a narrator to fulfill the role of Ann?

KH: As an audiobook listener, I primarily listen to nonfiction. I prefer to read when it comes to fiction and listen when it comes to nonfiction. Although I'm getting increasingly into fiction audiobooks as well, which I've been very excited by. So for me, the casting process was completely new. We received three sample narrators and we were asked to rank our sample narrators. I really enjoyed all of the narrators, but I think there was just something about Emily's voice that was really resonant to me and felt very authentically like Ann's voice. Because the book is told in first-person, it felt really essential to me to have somebody as the narrator who I felt like could fit in Ann's shoes. And there is something in Emily's voice, a kind of frankness, a no-nonsense quality, that really spoke to what I saw as Ann's Washingtonian roots and her kind of plain-spoken Western vibe, despite her aspirations. And so I really felt like she could capture that aspect of the narrator. And I have listened to her read the book and she certainly has.

HH: Totally. And I'm glad to hear you've listened. I was curious what it felt like that first time, especially as a debut fiction writer, how it felt to hear a performer narrate your work?

KH: It was absolutely the most jarring thing. Because, of course, I have been reading the novel aloud to myself through pass pages and through revisions and through drafts for two years now. So, to hear somebody else reading your work, particularly somebody reading it so beautifully and just so lyrically, I felt very surprised, initially. But then I felt like, by the end of the prologue, there was something in her voice that really allowed me to drop in to the narration and really allow myself to be taken on a ride by her. And I felt like that was really effective. So, after the initial shock wore off of hearing somebody who wasn't my own voice read the book aloud, I really enjoyed the way she kind of captured the atmosphere and the narration of the novel.

HH: I agree, she does such a great job. And it's not so hard for her to give this lyrical reading. The novel is truly so lyrically written and atmospheric on its own, magical almost in this way that it transported me. It changed my space and brought me to this new world, which I think listeners will really love. I think that's sort of the best of the best of fiction, is just feeling like you're right there. I feel like this novel really accomplishes that.

For my last question, now that you've released your debut fiction novel, I was curious where you're excited to go next with your writing.

KH: I am deeply superstitious, so I do a bad job talking about what I'm working on next. But I am currently working on a novel that is in many ways a sort of family mythology story. And it involves a family that is effectively cursed and kind of what happens when one of the daughters starts to unravel the mystery of that. That's what I'm working on now. Although, I have to say, again, it's sort of still turns on this question I'm always really interested in, which is, “What can we push ourselves into believing, when necessary?” So, I'm really enjoying working on that. It's set on the Island of Capri, off the coast of Italy. I'm really interested in books that allow us to travel to new and, in this case, absolutely magical and gorgeous places.

HH: Yeah, well, I cannot wait to travel there with you. That sounds great. That sounds like a vacation that I would not say no to right now. Thank you so much for your time today, Katy. And I really appreciate you stopping by to chat about The Cloisters.

KH: Thanks so much, Haley. It was great speaking with you today.

HH: And listeners, you can get The Cloisters by Katy Hays on Audible now.