Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

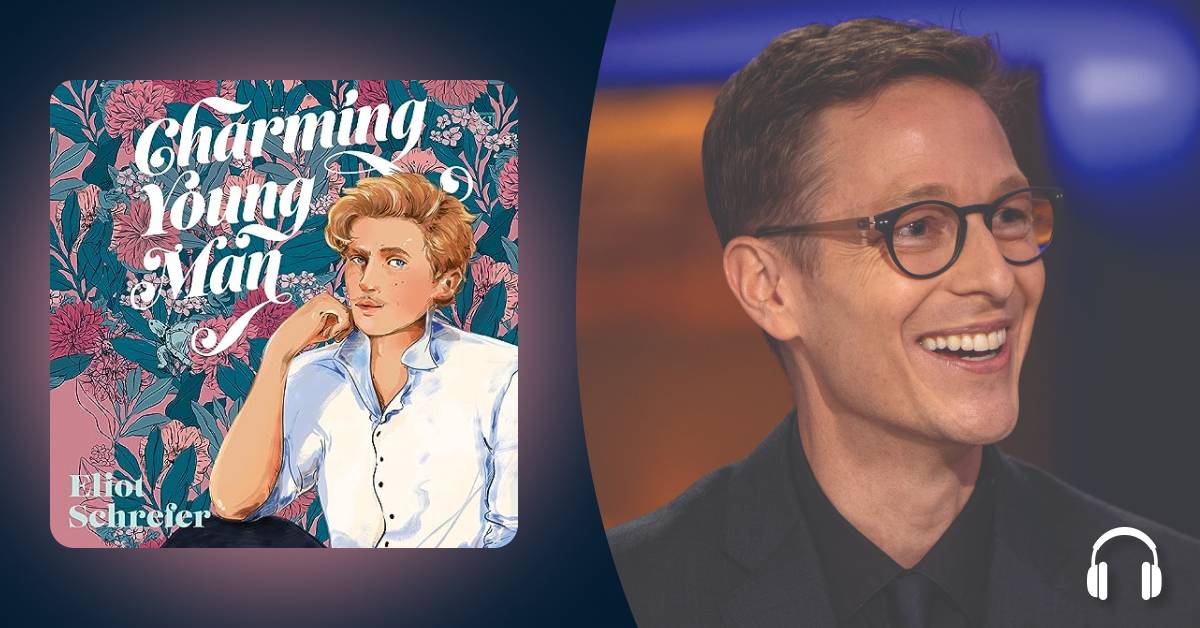

Michael Collina: Hi, I'm Audible Editor Michael Collina, and I'm so excited to be speaking with the bestselling author of Queer Ducks and Other Animals and The Darkness Outside of Us, Eliot Schrefer, about his new audiobook, Charming Young Man. Thanks so much for taking the time to chat, Eliot.

Eliot Schrefer: I'm so excited to be here. Thanks for having me.

MC: Of course. So, Charming Young Man is a young adult historical coming-of-age novel that follows Léon Delafosse, a real-life student at the Paris Conservatory and a French pianist of the 1890s. In addition to chronicling his musical ambitions, you also dive into his relationships and navigation of Paris society—namely, his interactions with a young gossip columnist named Marcel Proust and a poet count who was called the Oscar Wilde of France. What was it like writing from the point of view of these prominent and larger-than-life artistic figures?

ES: Yeah, it's a great question. I think I was helped with my main protagonist, Léon, because there's very little that's known about him. He shows up in Marcel Proust, who, decades later, well after the events of this story, came to write Remembrance of Things Past, his famous novel, which is still, by many, regarded to be the best novel in any language.

He (Proust) actually lampooned Léon. He comes across as a really social climbing, oily, unctuous guy. He's this violinist named Morel. Otherwise, what we know of Léon is ... there's his letters in the Paris library, which I went to, and I got to read his letters back and forth with Marcel Proust. And to be honest, I have college French, but Léon's handwriting was not good anyway. (laughs) It really was a real struggle to understand the letters, but I was able to make elements of them out. So, he's pretty much a blank slate. There's very little known about his life—especially the moments where he wasn't involved with these two much larger figures, the Robert de Montesquiou and Marcel Proust.

So those two, what was really interesting is to kind of peel back the legacy they have. Because I think Marcel Proust is sort of idolized as this great writer when he was in his 30s and 40s. But at this point, when Charming Young Man takes place, he was a 19-year-old gossip columnist, basically, and he was trying to work his way from the upper middle class into the upper class. So, he was also a sort of outsider trying to work his way through.

And it was interesting to try to find the real person there. And I think, when he pointed the finger in his book many decades later at Léon and said, "Oh, you're just a social climber," I actually see in Marcel Proust a huge desire to climb the ranks of society and do whatever it takes. And certainly as a gay man, you know, my memories of when I was in my teens and 20s were that there was a lot of us, (laughs) you know?

Like, people are trying to find out where the good party was that weekend and do whatever it takes to get there—and, hopefully, try to be wearing the right thing. And so, it was a way in which it has a lot of modern elements and historical. But the one who was the most outrageous historical figure was definitely Robert de Montesquiou.

I mean, this guy … this is all real. He had an Indonesian tortoise that had been crusted with rubies. A jeweler had put all these rubies on its back, and during his parties, it would wander through. And he had one of his own tears encased in a gold ring. So he wore this tear on his finger. And he really thought it looked great.

MC: I was curious if it were real—if that was a real element..

ES: That's totally, totally real. Yeah. And he actually appears in Proust as the Baron de Charlus, which is another one of the characters who's sort of, or is, an antagonist in Proust. And he's also in another novel by this author, Haussmann, where he's also kind of lampooned as well. But he thought he was going to be a great poet. He wasn't really famous as a poet—he was much more famous as a socialite. And the person who had this system of parties, which brought both the literary highlights of French society and the sort of wealthy socialite families as well.

"The 1890s were a really long time ago, and I think it's tempting to think that acceptance of queer people or LGBTQIA+ people just increased over time. But it was actually a watershed moment for really famous LGBTQ folk ... And within the walls of high society, there was a real queer acceptance in the time, and I was really interested in writing about that."

MC: Yeah, and speaking of those parties, you do a really great job of balancing the grandeur and the fickleness of high society during this period with the fear of being different and grappling with sexuality. Though the 1890s were far less accepting in a lot of ways, is there anything in particular that you hope listeners will take away from Lon's journey?

ES: The 1890s were a really long time ago, and I think it's tempting to think that acceptance of queer people or LGBTQIA+ people just increased over time. But it was actually a watershed moment for really famous LGBTQ folk, like Sarah Bernhard, the famous actress who would often dress in men's clothes and perform as a man. She actually played Hamlet on stage in Paris.

And within the walls of high society, there was a real queer acceptance in the time, and I was really interested in writing about that. You know, this way in which within these grand houses, there was such a love for the idea of non-heteronormative identities, but then, as soon as people would leave these parties and enter the street, you lived in this very Catholic society that saw this as a sign of decadence. That was a term that actually came to be in the 1890s, and it literally meant the fall—the “de cadere,” it means to fall. And it's like the fall from grace and the fall from morality of humans.

So there were these two currents going on. This larger-than-life kind of aesthetic, like zealous, like, "Let's, let's all be fashionable and beautiful and write poetry." And then also this countercultural movement that was saying, "No, this is actually wrong, and this is morally wrong." And those were coming to a head. And this is right around the same time that Oscar Wilde went from being the kind of literary light of London to being in prison after accusations of sodomy.

There's just so much going on in the 1890s that I think has actually a lot to say about 2023 as well, right? It wasn't just a slow slide towards acceptance. We see these pushbacks and setbacks along the way as well.

MC: Great, thank you. Though your version of Léon was incredibly talented behind the piano, he often struggled with the social aspects of society, and that decadence, because he's not from that world. So I wanted to ask, what made you choose Charming Young Man for the title? Because it doesn't always describe Léon as we see him.

ES: Every character I write, I draw from my own history. I remember when I went to college, I thought, all I have to do is study hard and do well, and then I'll get a good job down the road. And it was freshman year, and I remember it was April. I was sitting with friends, and they were all talking about which internships they got through their parents or friends of their parents or through connections. And I was like, "I don't have an internship. I was just going to scoop ice cream back home in Clearwater, Florida. Like, I'm not networking. Like, you guys are networking?"

I realized how much more of life is about who you know, and access you have through that, than I had ever imagined. And I think that was a big tension for me. I thought that was unfair, and I also just wasn't good at it—I was super shy. I basically went through all my classes in college never speaking, even though there were seminars. And I had a few close friends, but not beyond that.

And I remember thinking this sort of deep injustice inside me, right? Because I wanted to be a writer, and I wanted my writing to be the thing that mattered. And then I was worried like, "Oh, is it actually going to be about being at the right party and talking to the right person?" And so, I took that feeling I had back in the late 90s, early 2000s, and gave it to Léon back then.

He's got great beauty and great talent, but he actually has a huge insecurity about all these witty people all around him. He feels like he can't keep up—he has nothing to say. And I think that's a feeling that a lot of young people have now as well. And so, I guess by calling it Charming Young Man, I wanted to point to what in a lot of ways within this society is actually what mattered.

So, it's not a brilliant young pianist. It's ... are you someone that these houses would want to have invited to your salons because they could play the piano but also entertain and charm their guests as well? And I think for Léon, that's the big tension, because he has classmates at the Paris Conservatory who are really good at being charming—maybe more so than playing piano. And for Léon, it's the exact opposite. And his internal journey over the course of the book is coming to terms with that and figuring out, "Is there a way I could live a life eventually where it actually is about the piano?" And it's about real affection and not wit, or finding some way to impress people, even if it's not being totally genuine at the same time.

*WARNING: Spoilers ahead*

MC: And I find it so fascinating that you said that part of Léon kind of comes from your own experience and insecurity when you were that age. So I also wanted to ask about your author's note. Where you talk a bit about the research for this story, you reveal those circumstances in your personal life that made you see the John Singer Sargent painting that first inspired the story. What was it about the painting that really stuck out to you and inspired you to go down this rabbit hole of history of Léon and write about him and make him your own character?

ES: This book was 15 years coming. A long time ago, long before I met my now husband, I was dating a lot of different actors, and I've learned since then not to date actors. (laughs) Sorry, any actors who are listening—but I had a lot of bad experiences with dating actors and dancers in my 20s. I was dating this guy who was in the trial company for a Broadway show that was in Denver for the summer. And I sublet my apartment here in New York City, and then I went with him. I figured he would be at rehearsals, and I would write during the day. And anyway, we broke up on, like, day two. So I went to the airport. I couldn't go back home because I didn't have an apartment because I had sublet it for the summer, so I went to the United Airlines counter in Denver, and I said, "Where can you send me today? Preferably for under $200." Anyway, they said Seattle was one of the options, and my best friend lives in Seattle, so that’s where I went.

And I sort of licked my wounds. She took care of me on the weekends, but when she went to work during the week, I decided I would just wander Seattle and take in the sights. And I realized if I spent five minutes with each piece of art in the Seattle Art Museum that would take me from 9:00 to 5:00, and then I'll be ready to go meet her after work. And so, it was only because of that I actually spent time with pieces of art that I wouldn't have noticed otherwise. John Singer Sargent painted this painting of Léon Delafosse when he was on his rise—when he was in his late teens, and he was the toast of French high society. And it's not actually a famous painting by Sargent. It’s very dark—everything but his face and his hands is very dark. You don't see a lot beyond the face and the hands.

But what was there? I listened to the audio guide version of his life and looked at his face, and I felt this kind of communion across the 120 years that separated us. And I just really, I don't know, I saw a lot of my own story in his story. You know, when you're heartbroken, your emotions are right at the surface. Anyways. I was like, "Oh, poor Léon Delafosse." (laughs) Like, "He had such promise." Like, "He was supposed to be the great toast of society, and then he had this falling out with this count who poisoned all the connections he made for him, and he disappeared from history as a late teenager."

And that was just such a compelling, mysterious story that I really wanted to pursue it and write about it. So, I think, looking at his face, there's this guardedness ... Someone who's born into high society or born into the salon society might just feel like they deserve the limelight, but he seemed like someone who was more defensive and probably more reticent. And I know you can try to read a lot into a painting. So maybe someone else would have a totally different reading of this image, but I really felt like there was a complicated figure behind the painting.

MC: Well, I'm sorry that you were in the circumstances that led to you standing in front of that painting. But I'm glad we got this fantastic story out of it. You really did make the best of a not-so-great situation.

ES: (laughs) It was a breakup that was a long time coming, and it's good that it happened when it did and that we didn't go even further down this dramatic hole.

*End of spoilers*

MC: (laughs) And speaking of the research process, it's so clear from listening that you took so much time to really do your homework and your research. I know you mentioned you went to France to read a lot of those real-life letters. But I wanted to ask—how much is your creation and how much is reality and real fact?

ES: Yeah. I tried not to write anything that contradicted what was in the historical record, but at the same time, I definitely see this as a historical fiction not a narrative recreation of entirely true events. So there're ways in which they went to parties that I didn't know—they weren't in the historical record. Léon would have recitals that I didn't have historical confirmation for. But that was sort of, you know, the lie that tells the truth. That's what they describe fiction as. I just wanted to find the pieces that got to the truth, as I saw it from history, of what Léon's journey was. But I definitely let the story lead the way. And as long as I wasn't making anything up entirely, then I felt like it was okay to do. Because Léon was affiliated with Marcel Proust, who has become so famous—you know, anytime he was with Marcel Proust, there is an accounting for it. So I definitely knew about the length of their friendship and the places they would have gone together. And I got a lot of that from history.

MC: And when you were doing that research, is there any particular moment or letter that really stood out to you as this pivotal thing that had to be incorporated into your final story?

ES: So when I went to read Léon Delafosse's letters at the French National Library, it was so French. (laughs) Like, I had to show my credentials, then I got a yellow token that I turned in for a green token, and I got a blue token, and they finally sat me down in this stuffy room. And there was this velvet poof, and then they put his letters in this folio on this poof. And I had these white gloves on, and I was able to read the letters. And I realized how many of his letters were actually quite short.

The people he was writing to would write these effusive, poetic, lengthy missives. And he wasn't really a writer—it wasn't really his way of communicating. And so, that same sort of defensiveness or terseness that I saw in the painting also seemed to come through in the letters as well. But there was one of the letters … on the envelope, he had stuck a stamp on it. And the stamp actually sort of went over the edge of the envelope, and so the underside of the stamp was exposed. And so, when no one was looking, I took off my white glove in the library, and I actually ran my finger under the stamp. This place where over a hundred years before this young pianist had licked the stamp. It's a little weird (laughs), but it was like the communion moment of, actual physical communion of, this is where he had licked the stamp. And that was really wild to be in contact with it.

MC: Yeah. That sounds like it would be really powerful after you spent so much time just researching him and reading these letters and then crafting your own version of him for that story. I totally understand it.

ES: Yeah. As I was doing research, I ate a lot of French pastries and drank a lot of French wine. So that was also an important part of the process too.

MC: And a huge benefit too.

ES: Yeah.

MC: Huge benefit of being a writer.

ES: Yep. (laughs)

MC: I love it. This is your first historical fiction novel—you wrote sci-fi, you've written children's books, but this is your first real foray into historical fiction. So, aside from all of the research that you did, both the fun and maybe not so fun, was there anything different about your writing process for this story?

ES: There was. You know, I have this theory about writers that we have kind of a limited bag of tricks. Some of us have a bigger bag than others, but, narratively speaking, there are plot points we'll turn to often and character arcs we turn to often, like, in the characters that we write as fiction writers. And one thing I loved about writing a historical novel was that there were things that happened to Léon that I never would have dreamed of for a character if I was totally making it up from whole cloth.

And so it happened to him, so I wrote about it. Interestingly enough, for the reader, the book might be a little bit more twisty or surprising because characters that I've inhabited and I've written are doing things that Eliot Schrefer, the writer, wouldn't have had them do in any other circumstance. So they’ve kind of turned left when I was sort of making a narrative where they'd be turning right. And I think it kind of surprised me. And I think it also gives the novel sort of its own direction and flow, because one of the things I dislike the most when I'm reading a book is if I can predict in chapter one basically how the whole novel is going to go, and then it kind of dutifully follows through. When you're following a historical record—I mean, history is weird (laughs). People … things happen to them that don't fit the neat narrative, expectations, or what a writer would like in a neat, convenient narrative, and it kind of makes it, I think, fresher and more interesting. I've definitely come around to historical fiction, and I think this is not, definitely not, the last one that I would write.

MC: I'm so excited to hear that, because you, like I said, really nailed combining that real-life fact with your own creation and your own flair. So I'm excited for the next historical fiction from you.

"One thing I loved about writing a historical novel was that there were things that happened to Léon that I never would have dreamed of for a character if I was totally making it up from whole cloth."

ES: Thanks. Yeah, I think the big question I want to ask myself before I take on another historical fiction project is basically, "What couldn't a novel of its own time have accomplished?" And one thing with Charming Young Man is that novels that were published in the 1890s couldn't be as frank about sexuality as a book that's published in 2023 could be. And so, there's a really good argument there for writing a book now that’s set back then and not just letting the novels of that era do all the job. So I think, if I wrote again, it might be similarly a book in which I can write about and express something that wouldn't have been able to have been expressed during the time itself.

MC: And speaking about your next historical fiction, do you think you would ever revisit or expand any of the characters that you feature in Charming Young Man? Maybe with a story from a young Marcel or even a young Robert?

ES: (laughs) I don't know. Maybe you're going to write this book, Michael. You should—you should run with it. It sounds great. You know, honestly, Marcel and Robert both have sympathetic qualities, but they really serve as antagonists in this book. And because I'm team Léon (laughs), I think it would take a lot for me to come around to them and write their childhood stories.

But in order to write them, I did have to sort of sit and think about—What are their vulnerabilities? What are their sensitivities? What have they been through? Because they're the heroes of their journeys too. And so, they've got a version of their own story in which they are the most sympathetic figure. So it's always sort of my work writing is to figure out that side of things. But I really feel like Charming Young Man is a complete book in itself. So I wouldn't be looking for any Marcel Proust or Robert de Montesquiou fiction anytime soon from me.

MC: That's understandable. It definitely is its own story, and it's wonderful as is, so I don't think we're missing out on anything there.

ES: Thanks. Well, and listeners can write to Michael directly and see if he can take up the baton and write the next book. (laughs)

MC: (laughs) I'd have some pretty big shoes to fill. I don't know if I want to take that on.

ES: Throwing down the challenge. (laughs)

MC: (laughs) Well, let's also talk about narration. So, Mark Sanderlin is a personal favorite performer of mine. How did you decide that he was the person to voice this story?

ES: I just love his interpretation in this book. Even just looking at the cover of Charming Young Man, one of the things that we really wanted to highlight was this feeling of sensitivity and delicacy, both in Léon himself and in the kind of wallpaper background. It's not a brusque, tough book. It is a book (laughs) that has like delicate, delicate sensibilities and an elegance to it, and I think Mark's voice so captures that quality, this version of masculinity and maleness that has a real elegance to it. Mark was just, hands down, the perfect performer for that role.

MC: Yeah, he was great. He really nailed the performance. Like I said, he is a personal favorite of mine anyway, so I already think he can do no wrong, but it was a fantastic performance.

ES: Do you know he's also a pianist?

MC: I did not know that actually.

ES: Yeah, he wrote to me. I didn't know either when I suggested that they cast him, but then he wrote to me as he was doing the audiobook. And he said it's been a few years since he's played really actively, but he brushed off his piano and downloaded some music that Léon Delafosse composed and learned it. He said it was brutally hard, that it's very, very difficult pieces. But he worked his way through in order to get inside the character and to understand him even more as a pianist. So that was really, really amazing to think about. Like, he was recording Léon's voice and then actually playing Léon's music in the off time as well.

MC: That's incredible. That’s a side of the narration that I never would have expected, but it just makes this so much better.

ES: That's dedication.

MC: It really is.

ES: (laughs)

"It's not a brusque, tough book. It is a book that has ... delicate sensibilities and an elegance to it, and I think Mark [Sanderlin]'s voice so captures that quality, this version of masculinity and maleness that has a real elegance to it. Mark was just, hands down, the perfect performer for that role."

MC: So I also wanted to ask, are you an audiobook listener yourself?

ES: I am, yes. When I'm listening to things, I tend towards podcasts, and then I save my audiobooks for long car trips, when I really want to invest there. So, that is my main focus. I like narrative in all forms. Audiobooks, podcasts, printed books, movies, TV—it’s all what I live and breathe for.

MC: We're right there with you. Is there anything that you've been listening to lately that really comes to mind, are favorites of this year? What are you listening to now?

ES: I think the last book I listened to is Legends and Lattes by Travis Baldree. That was just such a cozy, fun fantasy novel about a barbarian who’s tired of the fighting life, and she just wants to start a coffee shop. That's actually the topic of the book (laughs) … figuring out how to get this coffee shop started and, you know, how to run a business in a fantasy town. And I just thought it was so, so delightful, and the audio experience was totally wrapped up in that.

MC: And he is also a narrator himself too.

ES: All these renaissance people who have all these multiple talents. (laughs)

MC: I know. It needs to be a group or something where we just highlight all of these renaissance folks.

ES: That would be amazing.

MC: So, is there anything else that you're currently working on right now? I know it's not a Marcel or a Robert story, but is there anything else you're working on right now that you can share with us?

ES: Yeah. I'm working on a sequel to The Darkness Outside Us, my sci-fi book that came out a couple years ago. The first draft just went into my editor a week or two ago, so I'm waiting for his notes. So I don't have a lot to share about the book, but that is what is going to be focusing my time for the time being.

And beyond that, on the historical fiction front, I was on a panel and someone asked, "What historical era would you be more interested in writing about?" And I realized I'd always wondered—What I would do as a gay man if I were born in, like, the Middle Ages? You know, sometime where it was really, really beyond the scope to even imagine living a life with another man. And I realized, I would join a monastery. Like, that sounds great. I'd illuminate manuscripts. I would make ale. (laughs) I would raise bees and conduct science and just live with monks on a hill somewhere in a monastery. Even though I don’t—I’m an atheist—actually believe in God, but it seems like the best life I could imagine in the Middle Ages. And so, I kind of imagined a book. What if a guy runs away—he’s basically chased out of town, he has nowhere to be, and he joins a monastery. And then, he slowly discovers that all the monks are gay. Like, every single one of them. So, it's a gay monastery book. (laughs)

MC: Sign me up for that book, because that sounds amazing.

ES: (laughs) Yeah, I think it'll be written for adults, and I'm just sort of teasing out the ideas now and figuring it out. So, I'm reading a lot of monk literature. I'm reading Pillars of the Earth right now, which is the late 80s huge hit about a monastery in the 12th century. And maybe I should switch over to listening to it. I haven't checked out the audiobook yet, but it'd be a good option.

MC: Totally. Before we wrap things up, I also just want to ask you if there's anything else that you want to tell us about your process creating Charming Young Man, or you want listeners to know.

ES: One thing I always like to let people know is I know what a big ask it is for we writers to ask you to give 10 hours—or seven and a half hours, I think, it's the length of the audiobook for Charming Young Man—seven and a half hours of your lifespan to spend time with a story. I always think of it as really an honor when people are willing to spend that time with something that I've created. So I just want to say thank you, and I hope to do justice to the time that you're willing to spend with Léon's story. And if you have any thoughts about it after you read it, you can always reach out to me on my webpage or all the usual places, like Facebook and Instagram and anywhere else.

MC: Well, as someone who did just listen to the entire audiobook, I can say, thank you for creating an amazing story. It is well worth the time, and I think listeners are going to love it.

ES: Thank you so much, and thanks for this really wide-ranging conversation. I had a great time.

MC: Of course! Thank you for joining us. I had a great time too. And listeners, you can find Eliot's Charming Young Man available on Audible now.