Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

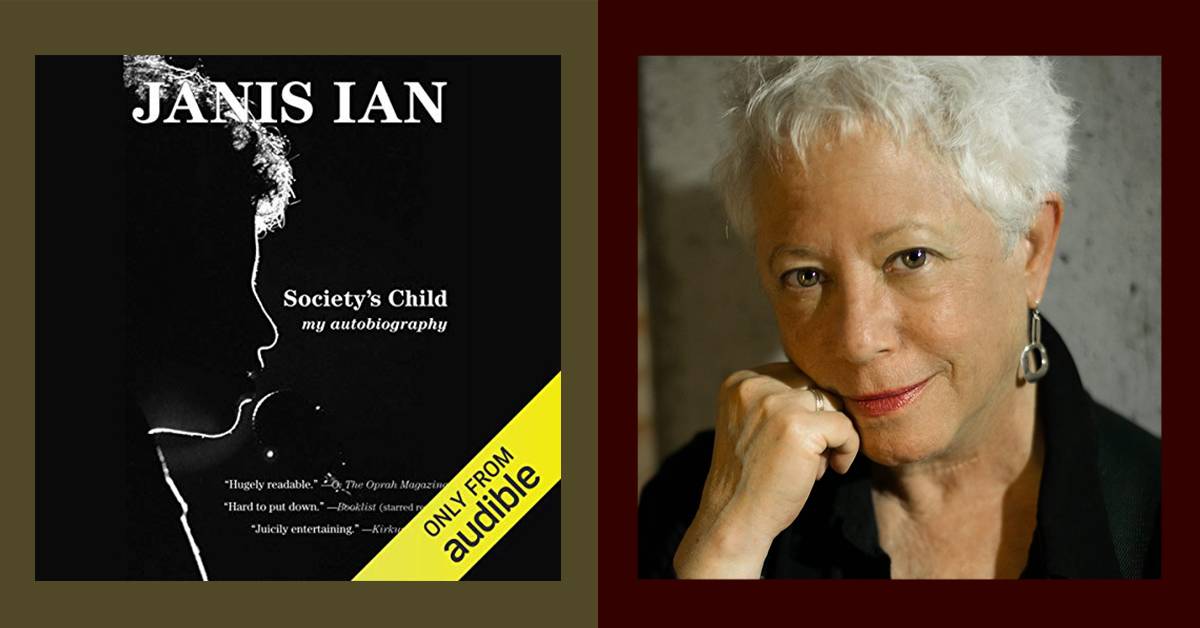

Christina Harcar: Hello, I'm Christina Harcar, Audible's history editor, and I'm in the studio today with Janis Ian. When Janis released the audio of her memoir, Society's Child, in 2012, it went on to win the Grammy Award for Best Spoken Word Album of that year. So I'm taking advantage of the 10th anniversary, more or less, of that release to invite Janis to speak with us by phone today. Hello, Janis, and welcome and thank you for making the time.

Janis Ian: Oh, my pleasure Christina. It's funny to think of it as history, isn't it?

CH: Oh no, it's more that I use history as an ever-expanding term to shoehorn myself into subjects I adore, don't you worry. I should give listeners a little bit of context about you today, which is that we're having this conversation just as you're getting ready to set out on your farewell tour, also featuring your next album, The Light at the End of the Line. And here at Audible, we're making your memoir, Society's Child, available on Audible Plus for a limited time. So, let's dive in. For anyone who hasn't listened to Society's Child, can you summarize it in one sentence?

JI: Black boy meets white girl and they have to stop seeing each other.

CH: Your memoir's title is also the title of that first hit, which you just summarized. This was completely verboten at the time. So, how does that song resonate for you across the years when you hear it?

JI: It's unfortunate that it still applies, because there's still so much discrimination. It resonates for me as an artist, it's an amazing calling card to have written "Society's Child" at 14, to have a hit from it at 15 and 16, to have been a has-been at 17. "Society's Child" is one of those records that comes along once in a lifetime, maybe twice if you're very lucky. In my industry they call it a career record or a career song. It's the song that makes or breaks a career and certainly "Society's Child" is that. I really hate that I'm still singing it because it's relevant and not getting to sing it as a nostalgia piece.

CH: I never thought of it that way because I do love the song so much. I wish it could be a nostalgia piece. In fact, the first anecdote in your memoir is about that song. It's a scene that has gotten more violent to hear over time in an odd way. It's about you getting harassed and shouted at by a crowd for having written this song. I'm curious, how did it feel when you had to perform that scene of violence for the audiobook? And how do you feel now when you look back on it, that moment of having to get on stage?

JI: It was not an easy scene to narrate. It's a painful memory and it will never stop being a painful memory. The only difference is that now I don't have to relive it every time. I can let it be a memory. I think it's also a good example of the danger of removing words from our vocabulary when we're referring to something that happened in the past or a way of speaking that was considered normal in the past.

CH: I wanted to give you a chance to say what was the most satisfying portion of the book to write and to narrate. And you can substitute fun for satisfying.

JI: I think writing that last chapter, getting to have a happy ending. I love happy endings. I just finished Oliver Twist, the actual book, and I thought, "Well, how satisfying," because my introduction to Dickens was Little Nell (a character in The Old Curiosity Shop), and I have never forgiven him for killing her off at the end because it came as such a shock to me.

My wife calls it my Pollyanna attitude. I love a happy ending and I feel like I'm getting to experience a very happy last third of my life. I had the first third where everything was, “Make everything work and become a great writer and become really famous,” and then the second portion, which was, “Oh my God, now I don't get to do any of it anymore, how am I going to climb out of this?” And then trying to climb out and get back on my feet. And now the last third, which is obligations and the lack of having to answer to anyone else's expectations. And in between that, I get to be with my wife, who I adore.

"I love a happy ending and I feel like I'm getting to experience a very happy last third of my life."

CH: As long as you keep racking up healthy years together, your happy ending can be as long as everything that came before it, you know? I wanted to touch on one more aspect of your audiobook. As a listener, I thought that music really added a whole new dimension. And then Dolly Parton at the end. Can you give me anecdotes to share about those collaborations?

JI: Dolly Parton is extraordinary. I don't know of any other word for her. As much as she makes light of a lot of what she does, she knows exactly what she's doing at every moment. There are very few people, let alone artists, who can achieve that. She is funny. She is professional. She is wicked smart. She has a plan. She's not inflexible with that plan. She's just astonishing. And she is generous, because for Dolly Parton to have recorded with me, who at the time had no record contract, no prospects of one, and was considered vitally unimportant in the scheme of the music industry, for her to go against her managers and agents, who were all telling her not to bother.

And for her to say, "No, I'm doing it, 'cause it's a great song, that's the end of the discussion." She sang with me at 9:00 in the morning on a weekend, on her one day off, and she had had to rebook the session because she had to go into the White House, which was a reasonable excuse I thought. And she showed up knowing the song letter perfect, brought her own copy of the lyrics, had her own water, did the song, was relaxed, and was marvelous. You couldn't ask for a better experience with another artist. Dolly Parton is what I try to be as an artist. I try to live up to my songs and my talent and she does that in spades.

CH: You have said that, “Art saves…”

JI: “…but there are times when it's easier to believe we can be saved and times when it's harder.”

CH: Right. So how do you see that at work in the world today? And how do you see your work as part of that today?

JI: Through all of the chatter, through all of the technology, I think you still see artists trying to comment on the times and help us through those times. I think you see that all the time with artists, not just when we contribute financially and with our time, but when we contribute with our spirits.

And I think that's an important piece of supporting the arts, because we tend to forget how empty our lives are without them. If you can conceive of a life without music, without painting, without art of any sort, if you're capable of conceiving that, I'm sorry for you because it shouldn't be something that you can imagine.

Of course it doesn't work all the time, nothing does, but do I think it's vital? Yeah. If you look at a rising civilization, a rising culture, whether it's Greece or early China or Japan or Russia, that civilization and that political system is supporting the arts. It may only be so that politicians can get their names carved in the side of beautiful buildings, but the beautiful building will endure and everybody will forget what the name stands for.

CH: Let's go back to talking about your work, because up until now we've been speaking of you as an author, but you are also a performer. That's the understatement of my day. You studied performance with Stella Adler and you are a storyteller with emphasis on the teller. Can you talk about how much your performance training influenced your audiobook performances?

JI: Honestly, probably not a lot. I was already a performer when I came to Stella Adler. David Craig, the movement teacher, told me that I should go to Stella Adler because he had nothing to teach me. And when I asked him why, he said, "Because she is 83 and everyone should experience Stella Adler." And he was absolutely right. I went to Stella and she opened an entirely new set of worlds to me and she gave me a vocabulary for my own work that I didn't have.

But in terms of what I brought to narrating from it, those were things I was already doing. I already knew in my songs the backstory of the characters when it wasn't directly about me. I already had the talent, if you will, and you can't learn talent. Stella used to say, "There are five pieces to any performance: there's the entrance, the focus, the energy, the exit, and the talent. And you can learn the first four, but you cannot learn the fifth. You're either born with it or not."

In all humility, because I think being born with talent should make you humble, I don't think that my education as an actor did a lot for my performances. My dad was a great storyteller. I grew up on storytelling, so that's probably part of it too.

CH: So, Society's Child will be available on Audible Plus, and I'm confident it will reach new fans, and by that I mean listeners who are new to audio and listeners who are new to your voice.

JI: I would hope so. I think the coolest thing about that book to me is that there's music weaving through it and that it's live music. The biggest challenge of that book was that I went in thinking, "Okay great, it's 22 songs, I'll just sing three lines from each one." It never occurred to me that I was going to have to take songs like “Fly Too High” that are band songs and suddenly be doing them solo. It came as a shock but it was great fun.

CH: Yeah, and it comes across. So what do you want that hypothetical new fan who has just listened to Society's Child to take away from the experience of that audiobook?

JI: I would say that you can be down and down and down and down and still get back up, and that's an important thing to cling to. Things will change, and in a year it will all be completely different. It may not be different the way you want it to be, but it will be different, I can guarantee that. The other thing is that audiobooks are as close to a live performance as you're going to get without being in the theater at a live performance. It is particularly in my case, one person speaking to you one-on-one, very much like a person talking to you in your living room, but you don't have to serve them coffee or let them use your bathroom.

Audiobooks are not movies. You have to use your imagination. You have to envision the characters yourself. And one of the things that I love and hate about movies is that they show me what the characters look like. I love that in an audiobook, you can imagine the pirates yourself You don't have to have a picture of that pirate in front of you all the time.

"Audiobooks are as close to a live performance as you're going to get without being in the theater at a live performance."

In my book, although there are no pirates in it, there are certainly plenty of thieves, and you can imagine what those people look like. You should take away a good, healthy dose of imagination; that's what audiobooks are for.

CH: I agree wholeheartedly, and thank you for saying that because that's what we believe at Audible about the value of performance. On that note, is there anything else you are burning to tell Audible listeners about Society's Child or what you're working on next?

JI: If you're asking me if I have one thing to say to the person who has listened to Society's Child, it's to buy my [new] album now because both are closing chapters and I think it's important to close chapters. So that wouldn't hurt. If you come away from the audiobook feeling like you've just taken a dive into someone else's life and come out the better for it, that's what I would hope for.

CH: And on that note, I will say thank you for your time and for your candor and wisdom. And, listeners know that you can find Society's Child on audible.com.