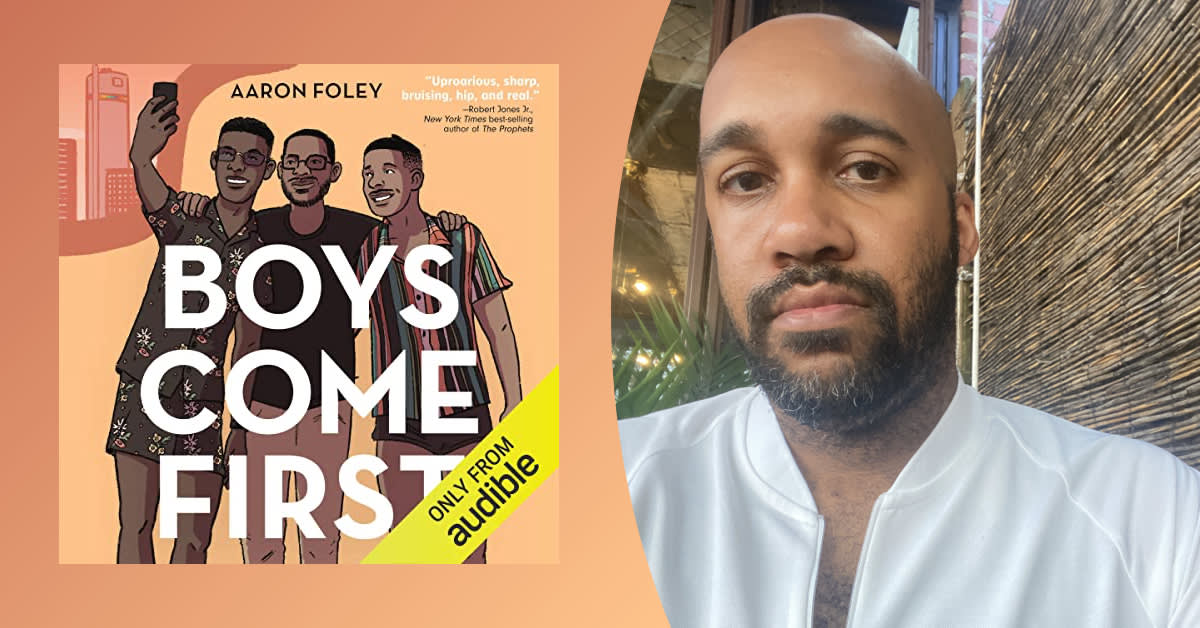

After years of writing nonfiction about life in his home city, the chief storyteller of the city of Detroit and editor of BLAC Detroit Magazine has written his first work of fiction. Aaron Foley’s debut novel follows a group of three friends in the Motor City, exploring their search for love, friendship, and professional success while highlighting some of the trials, tribulations, and joy that can be found at the intersections of race, class, and sexuality. Inspired by some of Foley’s own friendships, experiences, and desire for better representation in gay literature, Boys Come First aims to fill that gap—and it might just be the first great gay novel about being Black, queer, and millennial in Detroit.

Audible: Boys Come First tackles the intersections of race, sexuality, and class head-on. How did you weave these topics into the narrative?

Aaron Foley: I kept thinking of what I wanted readers to take away from characters who found themselves, as one of them describes, walking this tightrope while carrying all of those things. You’ll read about race and class often in fiction, but sexuality was more interesting to fit in. Many Black and gay men like the ones at the heart of this book are misunderstood because of presumptions about their identities. We think of gay men as having it all together because “it gets better”—they don’t, and whatever “better” is can be unattainable sometimes, especially for men of color. I think I weighed that part of it more than anything.

I wanted to approach each character long after their time in the closet and meet them where those three points are intersecting, specifically their queerness and how it’s not exactly like the kinds of queer narratives we usually see. One character wants to get married, but he doesn’t see a lot of Black gay men getting married, just white gay men over and over. But the presumption is that all gay men are allotted these fabulous weddings, right? Or how this same character is fetishized at one point because he is Black, which I know almost all Black gay men who have dated outside their race grapple with at some point—but again, the presumption is that gay men are all in solidarity with each other, and we’re the ones who should be extra careful about marginalization and being offensive.

With class, there are some things unique to Detroit that I can’t say is a universal experience for other places. There’s a growing tussle in Detroit of haves and have-nots that is far more amplified than I’ve seen in my lifetime, and I tried to put that into context by putting two characters on opposite sides of that. But here’s why Detroit is different: It’s a majority-Black city. You’d think everyone would be in agreement, but the truth is every Black person in Detroit thinks differently. Just because one person “makes it” doesn’t mean everybody’s going to love you for it. There’s a little of that in there but not nearly enough. I’d like to write more on that, because it does fascinate me.

Detroit is as much a character as it is a setting in this story. What was the biggest thing you wanted to capture about the city?

Detroit far too often is written about as a “gritty” (I loathe that descriptor), hardscrabble town where everyone has permanently grease-stained hands and is waiting for the auto plants to reopen. I wanted to show the kind of Detroit I know—first off, by centering three characters whose fortunes weren’t dependent on the economy but by the nature of the city itself, and second, taking the reader to places within the city and showing who else is there. Detroit can be fun, joyous, ebullient—I wanted some of that. It can hurt you at times but not always in that financially devastating, world-is-crumbling sort of way often seen in literature. And it produces its own culture that is unique to itself. I tried to capture some of this, from the little shout-outs to hometown artists (beyond Motown and Eminem) to an all-out description of a local dance we do called “the Tamia hustle.”

Most of all, Detroit is very, very Black—with influences from a little of everywhere, from Southern hospitality to Midwest nice to infusions of things Middle Eastern, South Asian, East Asian, Latin American—that, again, isn’t always seen in literature. I thought of The Turner House as sort of a North Star in writing my own novel, as I thought Angela Flournoy did an excellent job of educating readers about Black Detroit and drawing us into the lives of the namesake family.

We think of gay men as having it all together because “it gets better”—they don’t, and whatever “better” is can be unattainable sometimes, especially for men of color.

Boys Come First is such a character-driven story. And rather than focusing on just one character, the plot follows three Black gay millennial men. What inspired that choice?

Multiple POVs were common in African American contemporary literature of the ‘90s and ‘00s—think Terry McMillan, Eric Jerome Dickey, E. Lynn Harris, and the like. My mother, and nearly every Black woman I knew as a kid, had every McMillan novel on her shelf, and I’m not shy about pointing out that Waiting to Exhale was a major inspiration for Boys Come First. I think sometimes because so much of Black literature might center one or two characters, like a Celie or a Pecola Breedlove, we started to see more novelists try to explore the myriad ways Black people move in this world by introducing multiple characters at once.

For a story about Detroit, a city that at its peak had a million Black people living there and thus a million individual experiences, I wanted to show some commonalities among them but still have three distinct approaches in each protagonist. In Detroit, the high school you go to is crucial, since you represent that for the rest of your existence, and you either go to a neighborhood school, a magnet school, or a private school—there’s a character that represents each one. One character is more upper-middle class and another is decidedly middle-class—Detroit was once referred to as the capital of the Black middle class—while the third comes from more of a working-class background. And it’s not uncommon for any of these folks to all comingle in the same place in real life.

For a story about Black gay millennial men, I always tell people I wanted something my group chats of gay Black millennial men could discuss. One of the last books one of my chats discussed was the masterful The Prophets by Robert Jones, Jr., and we all read it because it was one of the rare stories, regardless of time period, that centered gay Black characters. But that was one of the only books, too. And I’m sitting here the whole time like, “OK, where’s our A Little Life? Where’s our Less? Where’s our What Belongs to You?” I’m not saying I want to read or write Black versions of these books, to be sure. But a guy I once dated recommended this slate to me. And while they were all good, I still felt something was missing. In writing Boys Come First, I wanted to do my small part so the next person wouldn’t have to feel that way.

What do you think is the most important part of creating a compelling character?

Every character had to be authentic, which meant I had to take off some of my own filters when writing them. I was hesitant at first to write Troy, a Black gay male character who toys with hard drugs and is on the border of substance abuse and addiction, but I’d be lying if I hadn’t come across any Black gay men in real life that don’t. They all curse a lot, and say things that Black people would call “family business” or “not in front of company.” Dominick has the worst luck when it comes to hookups, but these are stories straight from my own group chats and wine nights. And they’re all humans in modern times. Who amongst us, Black, gay, male, or otherwise, hasn’t dealt with ghosting, workplace micro-aggressions, or difficult relationships with their parents?

What does celebrating Pride mean to you?

One protagonist, Remy, makes a big deal of holding hands in public with a male partner, which is something straight people probably don’t think twice about. He wants to be loved out loud, and he deserves to be. That’s part of what Pride means—doing everything unabashedly, out of the shadows and in public. Remy is also uncompromising about who he is and what he wants. He may struggle to get there, but that compass is always pointing in the right direction. That’s another part of Pride, the kind of confidence that comes from knowing who you are.