Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly

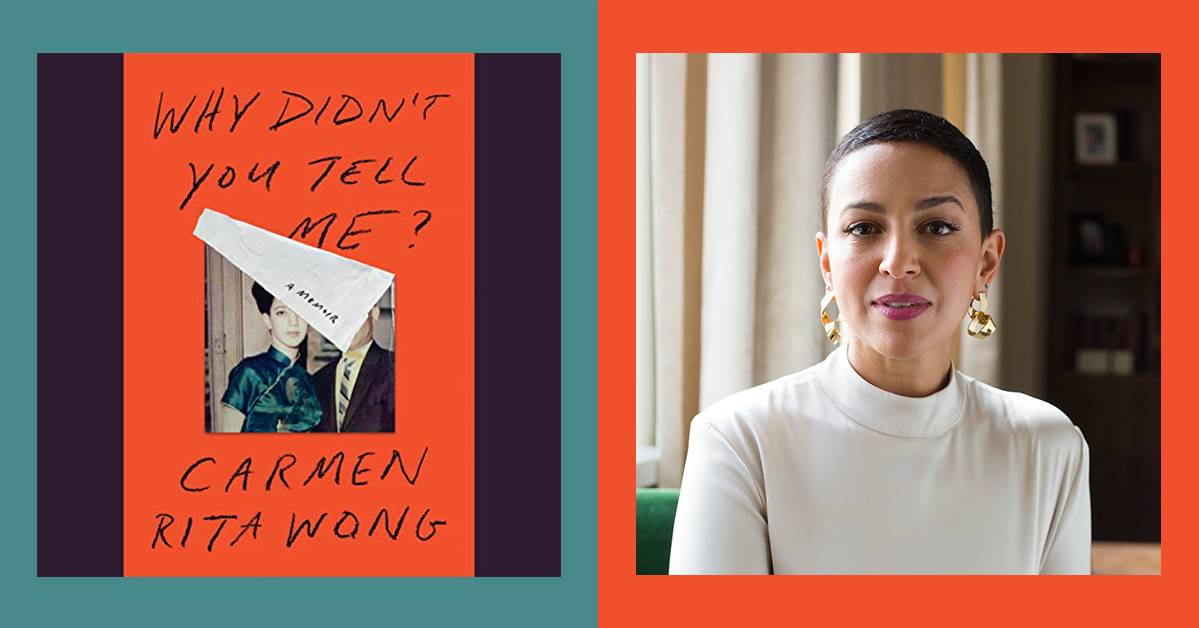

Yvonne Durant: Hello, this is Audible Editor Yvonne Durant, and today I have the pleasure and the privilege of speaking with Carmen Rita Wong about her riveting memoir, Why Didn't You Tell Me? It's about an immigrant mother, Carmen's mother, and long-held secrets that upend Carmen's identity and where she belongs in the world. There's so much to unfurl. We will not be giving away spoilers. Wong's book is a journey worth taking for all of us. To me, it is another important American family story.

Carmen, your book is amazing, how it lures you into twisty, unsuspecting, unique journeys. Tell me about the day you announced to yourself that it was time to sit down and write this book. Had you been taking notes all along?

Carmen Rita Wong: Oh, Yvonne, I tell you, I do feel like I have been writing this book in my head for decades. But in terms of actually sitting down, committing to a proposal, because this is actually my fifth book but my first memoir, I really did that five years ago. It took five years to bring this fully to fruition. I've probably written thousands of pages, but I felt like it needed to be told because, as you mentioned, this is a very American story, but original because it's just so intersectional.

YD: In the beginning of the book, you said that you changed names and descriptions. Carmen, your writing is so descriptive, do you really think that no one is going to know who you're talking about? Derek won't know you're talking about him? Because everyone was so real, so accessible, and so human, flaws and all. Are you expecting any calls from anyone?

CRW: I don't know if I'm laughing or crying. I think, as I also mentioned, I changed some names to not give satisfaction to certain people who like attention, but I did just try to respect people's privacy a little bit, and though I love really making sure that you know the characters as full people, I wanted to respect that just a bit. But yes, to be honest with you, I do assume that I'm going to be hearing from some people. Somebody texted me this morning about, for example, my book event, someone eating popcorn. Like, this is going to be one of those where people are going to be sitting there like a movie, like, “Okay, what tea is she going to spill? What's happening?” So yes, it's going to happen. I'm prepared for my life to change a bit.

"I do feel like I have been writing this book in my head for decades."

YD: Okay. Glad we got that out of the way. Your mother, Lupe, was a force. She was a little bit of everything. Radical, spiritual. I loved when she told you, "Just ask the universe for what you want. There's no competition but you.” She seemed very knowing on one hand, yet made some decisions that gave her a life she clearly didn't want, at least most times. Looking back, can you see that all she really wanted for you was the best and maybe was coaching you to aim high?

CRW: I think my mother was a very complicated person, but I don't think in the end that's necessarily all she wanted. So that wish fulfillment combined with projection, she really saw me as an extension of herself, as opposed to a separate person with my own dreams and hopes and fears, which she didn't necessarily encourage. I wanted to go into the arts. I wanted to be a writer and an artist and do all sorts of things. I wanted to act and perform, and these things were not encouraged.

It was very much her idea of what the American dream is or was. I'm not angry at that at all. She was a product of her time. Look, she came to this country at 15, did not have an education beyond that. She eventually got her GED, but she was a young woman thrown into a country where she didn't speak the language. She was essentially sold off to marry her first husband. She had very few choices and rights for her own. So, yeah, she did what she could do to make sure that I had my choices, and for that, I will always be grateful. Always.

YD: In light of Roe v. Wade being overturned, what would Lupe have to say about that? I ask because the subject of abortions comes up in the book, and Lupe was no stranger to them.

CRW: Correct. My mother had a few before it was legal. I was abortion scheduled number three, and the year that New York—it became legal. And, of course, it didn't happen, because here I am. But I definitely respect and wish that we all had this choice and maintain that choice. She became very hyper-religious, and I also think that looking at her and how she was very much looking into the part of this country that, on one hand, believes that when they need it, they'll find access to it, and on the other hand, condemn other people for it. That was my mother. She was that dichotomy. She was that "don't you dare get pregnant, don't you dare have an abortion," but, at the same time, would she want one for herself at some point? Sure, she did in the past. I think she really changed in the end. But I built my abortion fund when I was in high school, because you better believe part of that American dream was I wasn't going to let anything stop me.

YD: That was very impressive, by the way. I said, "Wow, she had her own fund." You were the only one doing that. Please.

CRW: Mm, I don't know about that. I think a lot of young smart women were probably like, "How am I going to pay for this if I need it? How am I going to get there? Where are the clinics? Who's going to be my cover story?" All of these things. I'm sure that that happened more than we know. I just don't think that most people are free to talk about it. I know if you asked me 20 to 30 years ago, I probably wouldn't have wanted to talk about it publicly. But, you know, I'm a former vice chair of Planned Parenthood Federation. You better believe I can talk about it [laughs], and I'm proud to talk about it, and with my 15-year-old daughter as well.

YD: Let's talk about Marty, also known as Dad. An interesting man. No doubt the love was there. It was admirable the way he treated you not as a girl but as a person who deserved to learn about things such as financial literacy, for example. Yet you learned, while he cared, he wasn't really caring for you and your brother. You were being funded under a separate budget. I know it surprised you. You lost your culture. Marty helped in stripping that away, and now, in a way, a family foundation that was there but not there. Yet you seem grounded, and so the anxiety manifested and you started picking at your skin. Did you ever think to reach out and ask for help?

CRW: Oh god, no. In terms of OCD and severe anxiety, no, absolutely not. One thing about Lupe and about this house was, as I mentioned, and why it's called Why Didn't You Tell Me?, full of secrets. “Be quiet.” “Don't complain.” “How dare you cry.” “How dare you be angry.” “I'll give you something to be angry about.” Or “I'll give you something to be sad about.” “I'll give you a reason to cry.” In that kind of atmosphere, there was no room or space for saying, "I'm falling apart inside."

I mean, my parents were part of the reason why I was OCD, the pressure to succeed in school, take care of my sisters, not complain, and, frankly, take care of my parents in many ways. It's that eldest girl in the family syndrome, which I know a lot of eldest daughters can understand this. So, no, I never could reach out for help, and I do think that that was a reason why I ended up changing my major to art history and psychology, because I was looking into being a psychologist and I have a masters in applied psychology because I suffered so much. And I realized that taking care of your mind and your emotions and your psychology is just as important as taking care of your body.

YD: I did not get the impression that you were or are a complainer, but you were pushed into adulthood at a relatively young age. You have four, count them, four little sisters to look after. Who was taking care of you?

CRW: I joke with my daughter, there was a line in a TV show we were watching together and it was perfect. “Who bakes for the baker?” Right? I wasn't lucky enough to have that. I did not have somebody taking care of me, so one of the things that I'm doing in midlife is, and with a lot of help, I've been in weekly therapy for almost 15 years, is re-parenting myself. I had to be my own parent. I had to be the person I leaned on and it caused a lot of anxiety and OCD and other things, so I've really done a lot of work to take care of myself and be kind to myself. And that's a hard thing to do. So I think it's going to be a long process.

"Taking care of your mind and your emotions and your psychology is just as important as taking care of your body."

YD: There's always work to do. Race. The conversation that won't go away, and for you being China-Latina, it was relentless. In school you were often asked to declare yourself, define yourself, and then there was colorism only to learn that it was in your family when your brother brought home his Black girlfriend. Yet, once again, Lupe rose to the occasion and defended him. You greatly admired her for this stance. But how frustrating was this to you? Do you still at times feel it? Are you asked to define yourself even though you've had great success, your own national TV show, you're a coveted guest on shows, you are a successful author. Yet, there's always someone or something tapping you on your shoulder about who you are. Race. Can we talk about that?

CRW: Yes, I am, as you say, ethnically, racially ambiguous. Actually, on the show 30 Rock there was a character that was based on me, which was played by Vanessa Minnillo. I think her name was Carmen Chang, and she was described as an ethnically ambiguous financial reporter. And they made a joke of it, and I had later had it confirmed with the writers’ room that that was based on me. It's not a joke. I've had it made a joke quite a few times. I've had people project their ideas on me. Poppy Wong [Carmen's father] passed away just a few weeks ago, recently, after being sick for a long time, which was painful in its own way because it's complicated with him. But even at the funeral home, the young man, who was third-generation Chinese from Chinatown, tattooed, taking over the funeral home himself, looked at me and said, "You don't look Chinese."

And so the question is always there. I don't think I can escape it. The difference is, it used to make me angry. I used to be defensive. Like, for example, I know I'm also African descent. I know I'm also a Black woman. And Latin and Latino is not a race. We come in all kinds of colors and flavors. And my daughter came out completely European looking and we would get questioned. I would get stopped when we would travel internationally. They didn't think she was my child, you know? So, I had to change my passport. I tacked her name onto my last name on my government documents so that people wouldn't question us.

It is a specter that will not leave me until this country figures it out, which I think is going to be quite a while. I think this is a quality of the nation that we live in. So, it's not going to be escapable. I just try to understand where people are coming from, and I'm tired of educating people, but I will continue to do so if I feel like someone's open to it.

YD: I can relate to that. I'm curious, did your brother, Alex, have to endure the same “who or what are you?” questions as you did when you lived in that predominately white community, Amherst? Did he go through this?

CRW: Well, as you read, they wouldn't let him join the football team because he was the n-word. The difference was in that in a mixed family, kids come out all different ways, right? My brother came out looking more, what do you call it? Blasian. Black and Asian. So, it was more so that they thought in New Hampshire in those days that he was Black and I was Puerto Rican. Whatever the heck that meant to them. To me, I was just like, "Oh, you mean my neighbors in uptown Manhattan? That's cool, Puerto Ricans are cool." But to them, that was a bad thing.

So, I think he didn't have to endure it as much because he looked like a Black man with Asian eyes. Kind of like a Tiger Woods, right? But yes, unfortunately for him, it was harder. He was a Black boy in New Hampshire, so his life was definitely harder in different ways.

YD: It's funny, while listening to the book and your encounters of racism, it seemed like an era of long ago, but you were talking about the ‘90s.

CRW: So, the ‘70s, we were in New York City, right? We were in Manhattan and it was no issues. Because we were with our Dominican family. Actually, our Dominican and Chinese family, so we came in every shade of the rainbow. But in New Hampshire, it was a different thing. So, that was the ‘80s, then Connecticut in the ‘90s, then even New York City, to this day, Yvonne. This is not escapable, to this day. And one of the unfortunate things is that whether it's dealing with my daughter and people not believing I'm her mother, this stuff happens, and you know in my professional life how much race was an issue.

I'll give you a funny story as opposed to a sad one. When I was on air at CNBC and I first got my show, they didn't want me to wear hoops. And I'm a girl who wears hoops all the time and they said, "No, no, no, no, no." And I was like, "What are you talking about? They're just earrings." "You look too ethnic. It's too ethnic." Now, I won that battle and then soon all the ladies were wearing their hoops. So, listen, it does not leave you. It all depends on the environment you're in, and in my life, fortunately or unfortunately, I have had to be in and work in majority-white environments.

YD: Did you ever feel like you were a token?

CRW: I felt more so, like, no, I have to be honest with you, I don't. And I'll tell you why. Because professionally in the ‘90s and early 2000s, my being Latina or Hispanic trumped everything, right? So, they saw me as being Latina and I have to say that the one or two Black coworkers I had, that was more of a token situation. But, as being Latina, it was “You're an assistant and that's it, and that's all you'll ever be.” You can't possibly be smart. In the book, I write about how I was told in journalism you can't be objective because you are a minority, which we know is ridiculous. If anything, they need us in journalism. But that was, it was a white world.

YD: So, at one point, you leave Amherst behind with your shag rug that included a green the color of wet dollar bills. That is some kind of green. You should get a job naming paint colors one day.

CRW: I swear I'll never forget that color.

YD: I can imagine. You find yourself working at Christie's, where walls are adorned with masterpieces, the very rich and famous visit for viewings, auctions, and for the parties. At one of these parties, two famous men were in the bathroom and you were asked to go in and get them out. How did that happen, and what was that like to go fetch Mickey Rourke and Tupac Shakur?

CRW: Let me tell you, to have my life in the space of like two years go from New England college and suddenly find myself on Park Avenue kicking Tupac out of the bathroom, and Mickey Rourke? I saw more celebrities that night. It was like those magazines that I was obsessed with all my teen years that I would pore over and note every single name in them came to life in, like, only my second job out of college. It was all right in front of me. But I was asked to get them out of the men's bathroom because I was the only brown person. Brown, Black, however you wanna call me, person of color that worked there professionally. Everyone else was either the doorman staff, and so they were like, "Well, we need someone professional to go in. Carmen can do it. Tupac won't be mad at Carmen. Oh, let me tell you, that was one of the most beautiful men I have ever seen. Beautiful.

YD: Yes, I love your description of him. I just want to talk a minute briefly about the time you lived in Santiago and Mexico City with your first he-who-shall-not-be-named, to work for Christie's. An eye-opening experience related to classism in a modern world that you saw in your own household.

CRW: It was quite the flip side of being a Latina in the United States. In this country, I was seen as a minority, as a Latina, right? In South America, I was seen as American. That was the first surprise to me. I thought I was going down to see my people. Absolutely not. The other thing is, I didn't realize, between Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, like, majority European in terms of who the middle class and upper class were. So, they called me Gordita, which is “little fat girl” because I wasn't a size two, and they called me Negrita, “little Black girl.”

"In this country, I was seen as a minority, as a Latina, right? In South America, I was seen as American.

But I'll say this, the class was very, very different. We were raised and I was raised on the idea of, and the history of, American slavery, right? I was raised to do everything from cleaning to picking up to whatever, no matter what job I had, right? I get down there and we have, in Chile, we have a housekeeper. The word they used, of course, was servant, who basically had a tiny room the size of a closet behind the kitchen refrigerator and she slept there. Just the size of a twin bed. That's all the room she had, and she slept there six days a week. And she had her own family someplace else. And, of course, she was Indigenous. And we were supposed to ring bells when we needed something, which horrified me.

I mean, Yvonne, as an American, this is horrifying. Especially an American of color. Are you kidding me? Ring a bell? There were bells in the bathroom, there was a bell next to the toilet. And I got up one night to get a glass of water and she got up and was horrified that I got up to get my own glass of water and didn't ring a bell for her. Shocking. But here's the other thing, her boss, whose house we were renting, called me one day and said, "Carmen, you've gotta let her do her job. She's very upset. You're not letting her do her job." So, I used the bells once in a while. Did it feel good? No. But did I learn a very good lesson on how our point of view as Americans and the way we kind of see the world, it is not the default. Even as a Latina American, even as Chinese, even whatever it is, it's not the default, and it was a big learning experience, living in those countries, absolutely. Which, by the way, I love them. My god, Santiago, Chile, and Mexico City live in my heart forever because I just love their people, I love the food, I love the art. It was an incredible experience.

YD: You left Lupe with so many unanswered questions. As a mother of Bea, what kind of mother are you and what kind of mother will you never be?

CRW: I am definitely not Lupe. I say that I basically parent in reaction to my mother. I decided to not be my mother as a parent. The things that I [am] handing down that come from Lupe would be a sense of confidence, a sense of entitlement, that we are just as worthy of everything that this country has to offer as white males [are]. That sense of entitlement. But, you know, education is important. But am I like Lupe in the sense of “If you don't get an A, life is over for you”? No, I don't want that. I don't need that. I want her to want to do well and want to be good, not for me. For herself. To be the best she can be at everything she does because it's important to her, not just to me.

Sure, it's important, sure, I don't want to be disappointed. Of course, I love seeing A’s on her report card. But she has long COVID, actually, and I have to mention that because it really forced me to give up a lot of the ideas I had of what success is and what success looks like for my child, because she is limited and she may be limited in the future. And it's very freeing, actually, to really nurture who she is as a separate individual as opposed to being an extension of me. The best thing I can do is have her know that she is herself, and I hope that for her.

YD: That's great. I just want you to know, I was with you every moment of your journey, your search, and when you thought you found the answer, I said, "Yay." And then one more surprise came and I said, "Well, I'll be damned." But I just wanna thank you for your brutal honesty, your rawness, and just coming clean. It's much appreciated and it's going to open the eyes of many people, so thank you for this great piece of work.

CRW: Oh, thank you. Thank you so much for having me and for sharing. And I have to tell you, recording the audiobook was one of the great big dreams of my life. So, I'm thrilled.

YD: You did a great job, by the way.

CRW: Yes, I loved doing it, really. It was a dream. I said, “One day, I just wanna be able to tape and record my own book,” and there you go. It was great.

YD: You did it, you came through. Thank you so much. And listeners, Why Didn't You Tell Me? can be found on Audible.com. Do not miss it. Listen up. Thank you.