Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

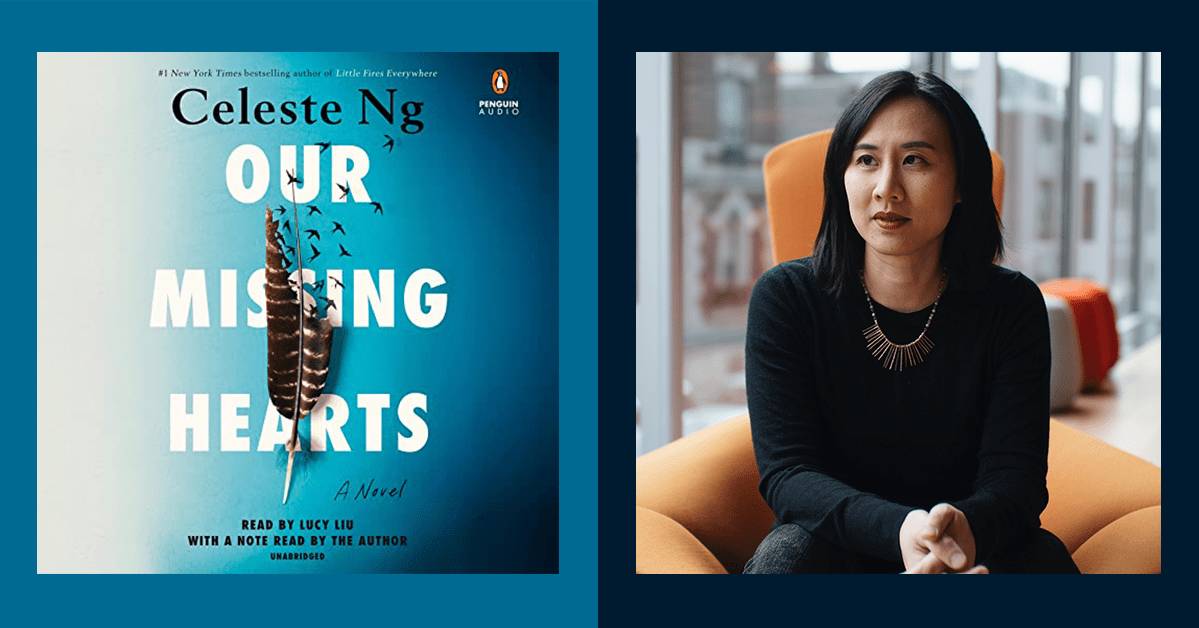

Tricia Ford: Hello, everyone. This is Audible Editor Tricia Ford, and with me is Celeste Ng, bestselling author of books like and . But we're here today to talk about , her latest novel and my favorite listen of the year so far, performed by Lucy Liu and including an author's note read by Celeste Ng herself. Welcome, Celeste. Thank you so much for being here today.

Celeste Ng: Tricia, thanks so much for having me here. I'm really excited to talk with you.

TF: Now, at first glance, Our Missing Hearts seems like a departure for you. It's a dystopian story taking place in the near future in the wake of this fictional PACT Act, which stands for Preserving American and Culture Traditions, which is legislation that the government passes to oppose foreign cultural influences in the US. They do things like reassigning custody of children whose parents are accused of being un-American. But after listening—and I like my dystopian stories as much as the next person—I was very pleased to find that it clearly has all the heart that you'd expect from a Celeste Ng novel. But I would love to hear in your words how you would sum up the story.

CN: Yeah. It focuses on a young boy named Bird. He's 12 years old. And he's really growing up in a time that's shaped by fear. I think it'll sound and feel familiar to many people who are listening. In his world, it’s a time of really deep anti-Chinese sentiment, and the authorities can take away the children of anyone who's deemed to be acting un-American, which often ends up being those of East Asian descent or anybody who speaks out on their behalf. And Bird's Chinese American mother, Margaret, has left the family some years before. And at the beginning of the novel, Bird gets a letter from her that's kind of mysterious, and he's drawn into this quest to find her and to understand why she left their family.

Ultimately, what ends up happening is he learns not only why she left, but also about how to hold on to hope in a time where it feels like everything's very dark. And for me, that's really what the story is about. It's really a story about a family, about parents and children, and about how to keep yourself going when it feels like the world is in a very bad place.

"It's really a story about a family, about parents and children, and about how to keep yourself going when it feels like the world is in a very bad place."

TF: That's a great summary. I think it gets to the heart in the story, and the remedy has so much to do with those connections.

CN: One of the questions that I've been wrestling with over the past few years has really been this feeling of “What can one person do?” It feels like you're all alone in the world sometimes, especially since the pandemic. We were physically isolated from each other a lot of the time. It feels like the problems that we're facing are so insurmountable, whether they're climate change, whether they're societal issues, really all of the above. And that idea of finding connections with other people, finding other people who care about the things that are also important to you, and finding through that community the strength and willpower, and even just the power, to try and make the world better, that's been something that I've been thinking about a lot, over the past few years in particular.

TF: Now, you talk about it in your note at the end of the book a little bit, but I was intrigued by how your process is influenced by current events and how your writing pivoted in response to that. Could you talk a little bit about that?

CN: Yeah. I originally started this novel right after I finished my second novel, Little Fires Everywhere, and I thought of it first as a fairly conventional story about a mother and a son. It seemed fairly realistic to me. I was thinking about a mother who was creative in some way. I was working out if she was a writer, if she was an artist, but I had this idea that her son didn't fully understand why she was so drawn to this other thing, and maybe even saw that other thing as a rival for him in some way. And would they be able to understand each other? Would he understand why this was so important to her?

And this was in about October of 2016. And so fairly soon after that, the 2016 election happened. We saw the rise of the far right. We saw all of the things that happened during the Trump administration, and then we moved into the pandemic. And what happened was that the world outside my writing room became so bleak. It felt like we were living in a dystopia, and that feeling of fear and of the world kind of slipping away started to creep into the book. And at a certain point, it felt like in order to try and understand the questions I was asking myself as I was writing the novel, the book itself needed to acknowledge the kind of dystopian feel of the world that we were in.

And so I started writing, as you can see from the author's note, into that other world that wasn't quite ours but was maybe just ours with the volume turned up a little bit. And it felt really important to me to acknowledge that these things are not new and that we've been through many of these things before in the world. They're still happening. And so I did a lot more research for this book than I would normally do for a novel. I wanted to understand what had happened before so that in some ways I could better imagine what might happen in this world.

TF: Interesting. That shows through in the authenticity of people's reactions, and how it's outrageous what people are forced to do. And at the same time, it just all feels very possible.

CN: Yeah. One of the scary things that's happened is that as we approached the publication date, many of the things that happened in the book are starting to happen in the real world. The recent problems that librarians have been facing, especially school librarians, about what books they're allowed to put on the shelves or which books are seen [by] some people as harmful to the children, right? You've got librarians who are facing death threats because they dared to have a book that features a queer character. There's something about that that feels terrifyingly dystopian, and yet is in the news now, right? And not just one case, but many. There's many other examples of that too. But like you said, I wanted it to feel real. I didn't want it to feel like something that was dismissible, as saying, "Oh, that's completely made up. That's far-fetched. That could never happen."

TF: That definitely shines through. In part, it's the characters. These feel like real people and there's a bunch of really brilliantly depicted, authentic characters, but none more than Bird and Margaret, the son and mother. And I'm curious how you approached each of them. In particular, what it was like to get into the head of a 12-year-old boy.

CN: For me, story always comes from character. And so you're exactly right. I really had to get to know all of the characters, but in particular the two that we spend the most time with in the book. Bird, who is this adolescent who's spent a good part of his life without his mother, and then his mother, who has been away doing other things that we learn about, but has been thinking of him. He's very important to her despite what he fears. And whenever I start a story, I always start with the characters. And usually, I try to get to know them almost as if I'm getting to know somebody at a party. You meet someone, you say, "Oh, where are you from? What do you do? What do you like to do for fun? What's your favorite TV show?" You know, those kinds of surface things.

And I do this by writing a lot of things that never end up in the finished book. I'll open a new document and just kind of write about this character, chat with them almost as if I'm chatting with them at that party, and what I find is that you start to get to know something about them as a whole. You start to understand them. You start to get a sense of what their deal is, for lack of a better word. Like, "Oh, you don't get along with your mom. Why do you not get along with your mom? That's interesting. How did you feel about that?" That's, for me, how I always get to know the characters.

And one of the things that I realized as I got to know Bird, in particular, who's the character that opens the book, is that he's been in a very sheltered world. He's young, first of all, so he hasn't experienced a lot. He's got a limited range of experience and also a limited vocabulary in some ways, and a lot of his understanding about the world has really been framed by his father, who's trying to protect him. You see how at the beginning [Bird] kind of parrots back some of the language of the law that's been given to him. It's like a homework assignment. And then, as the novel progresses, he starts to open up. His sense of what's out there in the world becomes larger and the language starts to do that as well. And so by the time we start to find out what Margaret's story is, I think of the book as having opened up a little bit. And then we get towards the end of the book, we're seeing a much wider world. And for me, that kind of mirrors the coming of age that Bird gets as a 12-year-old. It was a fascinating age to write about.

TF: He's so endearing. He's so smart and clever and so much like both his parents and his own person. He was an easy character to root for and to follow and to fall in love with, for sure. And Margaret is one who, for me, grows on you because that initial shock of why would a mother leave. I'm curious how you approached her and that kind of dichotomy of mother and artist and activist.

CN: For Margaret, I almost approached her in the opposite direction as Bird. I knew that in this world, she would be perceived in one way, as an activist or as a threat. Or to Bird, she's perceived as an absence, right? And then I had to move from that to drill down in a way and focus all the way back to her as a parent and as a human. A lot of times what happens is when we have an idea of somebody, when they become an icon, we forget about their humanity. We forget about all the messiness and the particularity of who they are. And so for me, a lot of writing Margaret was getting down to the nitty gritty of her life and who she was, the things that she liked to do, what she was like as a parent before she left the family.

And once I was able to access that, I could understand who she was, and hopefully bring the reader along on that same journey of thinking of her first as this person who left her child, and then humanize her. She's always been human, but to show her humanity and to show the reasons that she might've done that, and to show the relationship that she had with her son, and the relationship that she wants to have with her son, and the kind of world that she wants him to live in. Her journey is almost the opposite of Bird's. If his is an opening up, hers is not a closing down but a focusing where we can suddenly see her as a very specific person, and their paths cross and that's where the story happens for me.

TF: It just opens up a so much deeper understanding of Bird and just how much of her is in there and how much she unconsciously planted really important things in him.

CN: When you're a child, you don't always think of your parents as people, as strange as that sounds. They're all you know. It's like that old joke about the fish saying, "How's the water today?" And you're like, “What's water?" Because it's all around and you don't actually know what it is. Only when you step out of their sphere, their bubble, and you get some distance from them that you can start to understand them as people. You start to have those moments where you go, "Oh, my mom was young once, and maybe kind of cool?" Or "Oh, I didn't know that you liked Bon Jovi. That's not a thing that I thought parents could do." You suddenly start to see their texture and nuance and their individuality.

And I think that kind of slow reveal in the book mirrors Bird starting to see his mother as a person, not just his mother, but as a person who has ideas and wants and fears and hopes of her own. And that's something I think a lot of us can relate to, that sense of suddenly having to grapple with the fact that our parents are actually people.

It's happened a few times where I just keep realizing, "Oh, there is so much more to my parents’ lives and to them as people than I even realized." It happened to me as an adolescent and then again when I went away to college to live on my own. And then again, now that I'm a parent. I really see things differently. I don't pretend that I understand what my parents' lives have been like, [it’s] more that I understand that I don't understand what it was like for them as young parents, what it was like for them as immigrants to a country where they didn't have family and where they were really trying to make a whole different life for themselves. I now know that there is this huge well of information and feeling and experience that I might be able to get a couple drops out of, but in a way, I recognize how vast their experience is. And it's kind of profound to think about in that way.

TF: It is. And Bird's experience with this very unique mother/son relationship and world situation is the spark of that first realization. It is a really special time to capture in a young boy's life.

CN: I think part of that is because right around that age of, you know, 12, 13, where you're really becoming an adolescent, you're at this turning point in your own life, where you're not quite an adult, but you're not a kid exactly anymore. And you have a certain amount of ability. You're bigger. You're taller. You can make some grownup decisions, but you're not equipped psychologically or emotionally to do that, right? And sort of the idea that you can get yourself into a lot of trouble because you don't know enough yet to make good decisions.

And at the same time, you're not given agency by the world around you. You're still often being treated like a child. You're sort of tip-toeing into this adult understanding of what the world is like. I think that's one of the reasons that I am often drawn to writing about adolescents and teenagers, because that just seems like such a potent point in your life. That's the moment at which you start to figure out what your place is in the world, and you start to get a sense of what the big picture is. Where before, maybe your world has really been very small—just your family, just your school, just your friends. Suddenly, you're aware of how much is out there.

TF: It's a special time to capture. And I know you do it with understanding and a sophistication. It's not YA. There's nothing YA about this. I keep going back to the word authentic, that Bird seems very real. As a grown adult, I can get into Bird's head through your writing and relive it in a really special way.

CN: Thank you. That's sort of my goal as a writer always is that whatever the character is, whether it's something you've experienced or not, that you can feel yourself in their shoes, so to speak. You can kind of feel their feelings to a certain extent. I think that's one of the most powerful things that any writing, particularly fiction, can do is it can really ask you to think somebody's thoughts and to feel their feelings and then hopefully to come out of that reflecting on your own life and your own experience. Hopefully, it opens up something for you as a reader as well. That's wonderful to hear.

"One of the most powerful things that any writing, particularly fiction, can do is it can really ask you to think somebody's thoughts and to feel their feelings."

TF: And that kind of goes into this other theme of the role of storytelling and the importance of storytelling, and the folktale at the center of the story with the cats and the hidden message, where you talk about the interpretation can be different for everyone. And over time, it changes and kind of becomes what every individual who's hearing it needs. I just thought that was beautiful and so true, and beyond that one central folktale, just the importance of storytelling in general. I would love to hear you talk about that. And I actually have a clip that I would love to play and then get your ideas.

CN: Great.

TF: It's from Chapter 14. This is a flashback between Margaret and Bird, and she's been telling him stories about nature, talking about how she would tell him folktales, and this final line kind of explains why.

Lucy Liu: "She filled his head with nonsense, with mystery and magic, carving out space for wonder, the haven in their long-ago Eden."

TF: I know that's super short, but the whole lead-up to that line, and then that line ultimately really stuck with me and the idea of creating an Eden and passionately wanting to instill that sense of wonder in your child.

CN: Stories have always been the way that I made sense of the world in a way. I was a really early reader, so I was then an early writer, and I was always making up stories. I was always reading stories, and my parents were very big readers also, so our house was crammed full of books.

And one of the things that I realized was that a lot of times the story would sound differently to you depending on where you were in your life. It's been a huge joy to go back to books that I remember loving as a child and read them with different eyes now. They sound different to me, and they speak about different things. The words on the page, of course, are exactly the same, right? The only thing that's changed is me and where I am and what I've experienced. And that's part of the magic of storytelling for me. It's a way that we make a narrative of the world, which, for me, means you understand a cause and effect. You understand this thing happened because of that. It explains something to you.

And then at the same time, your perspective on that changes. And so what it's explaining may be really dependent on the circumstances that you're in, and I think that's fascinating. And, particularly, it's clear that that happens with folktales, because there's a reason that they end up being so timeless. Because in a way, we keep coming back to them. They're just simple enough and yet they have enough depth and space that we end up finding different meanings in them.

I've always loved retellings of folktales. There's a poet, Anne Sexton, who's written an amazing collection she calls Transformations, in which she retells fairy tales in verse. And she takes them in a very different direction than the original fairy tales that I remember being told as a child. I remember reading her work when I was a teenager and just having my mind blown that she had taken the story and she'd turn it around and it looked completely different to me. And then, of course, if you go and you read the original, unsanitized, unexpurgated versions of many folktales and fairy tales, including Grimms,’ you see that there is actually a darkness and a depth in there, and that those stories have changed over time.

So, one of the reasons that I wanted to talk about that and use that as one of the themes of the book is that even the stories we tell within our families, I think, take on different resonances as we grow, as we learn different things and so on. The stories that Margaret tells Bird in some ways are her passing things on to him, but in other ways, they're sort of her giving him an opportunity, or as it says in the excerpt that you had, of holding open a little space for him to interpret and to play and to see different things. It's almost as if rather than giving him a picture, she's given him a frame, and he can hold it up over different parts of his life, and he'll see different things in it depending on where he is and what he's experienced. Storytelling, for me, is always one of the most magical things, and so it made sense that it worked its way into the book as a thing that this parent was trying to give to her child.

TF: Yeah, it's incredibly moving and important, and it carries through to the end. And what she gives him—this might sound overly dramatic—but it just might save the world. It's that important. And just beautifully rendered between them and something I take from the book with me.

CN: In the writing of this, I was asking myself a lot of questions about the purpose of art, stories in particular, because I'm a writer, but also any kind of artistic or creative work. I think especially during the pandemic, I found myself feeling really helpless and kind of useless. I would look at first responders, I would look at medical staff, and I would think, "Okay, that's what I should be doing. I should really be tangibly helping someone you can see: 'You could save this person. You have done something.'” Right?

And for someone who has the privilege of not working with my hands and of just getting to sit here and play with words and make up stories about people who don’t exist, I sort of thought, “What am I contributing here?" And so this is one of the questions that I was asking myself as I was writing the book, and I think that's one of the questions that the characters in the book grapple with as well. And what I came away with—I hope it's true—is that in some ways, art is serving a role. It won't all by itself probably change the world, but a lot of times what it can do is it can remind people of why they're doing what they're doing. It reminds people of not just what they're fighting against, but what they're fighting for.

Also, sometimes it can bypass the rational, logical parts of us, the parts that would say, "Oh, that's not about me. That's not my problem. I'm going to look away." Or the parts that will ignore new stories or statistics or more logical, rational arguments. I think a lot of times art can hit you emotionally in a very direct way. And in the best scenarios, you're changed by that. You start thinking about what it is that you actually care about, because that thing moved you. It made you feel something. And that means that art might not save the world. Books are not the silver bullet for all that ails us, much as I wish they were, but they might be something that can inspire us to take the actions that we need to. And so that's one of the questions I think that I was exploring in the book and one of the things I hope readers will take away: What is the role of art in changing the world, what can it do, what can't it do, but can we use it? What value does it have?

TF: There's a part of the story where it's like an art prank movement that happens. And it's very fun.

CN: Fighting injustice is always going to be hard work. And the easier and more manageable we can make it, the better. I think even more than fun, I think hopeful is maybe the way that I'd think about that. The art pranks that happen in the book are inspired, among other things, by the idea of guerrilla art, which is not in a museum, not in a gallery. They pop up on the street corner.

So, you can think about, for example, these installations that an immigration rights group called RAICES did in a number of different cities right around the time when attention was really being focused on family separations at the US/Mexico border. Imagine you're walking to work and you're on your regular commute. You are thinking about whatever's going on in your life, what you have to do that day, and you walk past a street corner and there's a cage. And inside that cage, there's a figure that's a small child-sized figure, and it's wrapped in a Mylar blanket. And what you hear is the sounds of children crying. That is the kind of art that can really pull you out of your everyday life and make you pay attention, right?

"Fighting injustice is always going to be hard work. And the easier and more manageable we can make it, the better."

And I think that's really valuable, that sort of way art has of focusing our attention and of not letting us just zone out, but of saying, "This is important. Pay attention to it, even if it's just for a second." Sometimes it's fun and sometimes it's joyful. It's revelatory in a way, and that kind of surprise element of it is something that we do need a lot. We need that to wake us up, we need that to make us pay attention, and we need that to kind of remind us of what we're doing.

TF: You hear from all kinds of people, the need of a shake-up, and some people's thoughts go violent with that, but why not art? That shakes you up just as much. And the malaise that you talk about, I think lots of people are fighting that, are coming out of that. Just a positive reminder of what's important—

CN: I think that's exactly right, just what you said, a positive reminder of what's important. It's often when you are dealing with injustice or you're dealing with a system that is sort of designed to keep groups in their place, it's easy to get caught up in what you're fighting against because that's often clear, right? It's also really important to remember what you're fighting for. You're not just fighting authoritarianism, and you're not just fighting censorship, you are also fighting for freedom of information, for diversity of opinion, for different viewpoints to be a quoted value.

I think it's important to remember both of those things, and so I guess that's where the hope part comes from. It may not be fun, but it's a positive reminder that you're not just against something, you are for something else.

TF: I do want to pivot the conversation a little bit because I want to be sure to give Lucy Liu big props. She does an amazing performance. Obviously, an actress I'm familiar with from many roles in film, TV. She's done a couple of other audiobooks, but this is her first full one from what I could find, and she knocks it out of the park. She's so great.

CN: She's so good.

TF: And I was just curious how you two found each other.

CN: We were thinking about who we might reach out to, to narrate the audiobook. And this was a case because one of the main characters is a Chinese American woman, and we wanted to see if we could have someone who maybe would have a personal connection to some of those experiences. And Lucy is an actor that I have just admired for years and years and years, way back starting with Ally McBeal. And then throughout, she's been one of my heroes, one of the people that I looked at and I was like, "I didn't know that we Asian women were allowed to do that. Cool. That's awesome."

So, we reached out to her, and I was thrilled that she responded to the book, and I think that shows in the recordings that she's done. She's also a parent, and so I think that aspect of the story had a particular resonance for her. And then, of course, she's just an amazingly talented performer. And so I was really thrilled that she agreed to do it. And, of course, she did an amazing job.

TF: I love finding a perfect pairing, because the story's incredible, it deserves a great performance, and it gets one. And I just encourage everyon—listen, read, however you get it, go and get it. And I'm curious also, whenever I finish a book I love, I'm like, "What is the author working on now? What can I get next?"

CN: I'm trying to figure that out myself, honestly. I'm sort of in the thick of doing interviews and press and I'm going to go on book tour very soon. So, I always find that when I'm writing, I need a little bit of a quiet brain space. And I think once this book tour is done and I've had a little bit of a chance to catch my breath, I've got a couple ideas. I have to follow those threads and see where they lead, but I suspect that, like the first three books, they'll have a lot to do with family relationships and with the ways that people who are close to each other and love one another don't always understand each other and are struggling to understand each other. And then questions about identity and race and about the role of art. I think those are the wells that I keep coming back to.

TF: Well, I'll be looking forward to it. I understand that need to observe the world around you in between creating new worlds, for sure.

CN: A friend of mine who's also a writer refers to it as “the fallow field.” The field gets depleted after a number of crops and you have to let it be and let all the nutrients ease their way back into the soil before you can start again. And I like that idea in a way, that you have to refill a little bit before you know what you're going to do next.

TF: This is one of those books that I love so much. Thanks to everyone for listening, and thank you, Celeste, for joining me today.

CN: Thank you so much for having me on. It was a pleasure.

TF: You can purchase, download, and listen to Our Missing Hearts right now on Audible.com.