Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

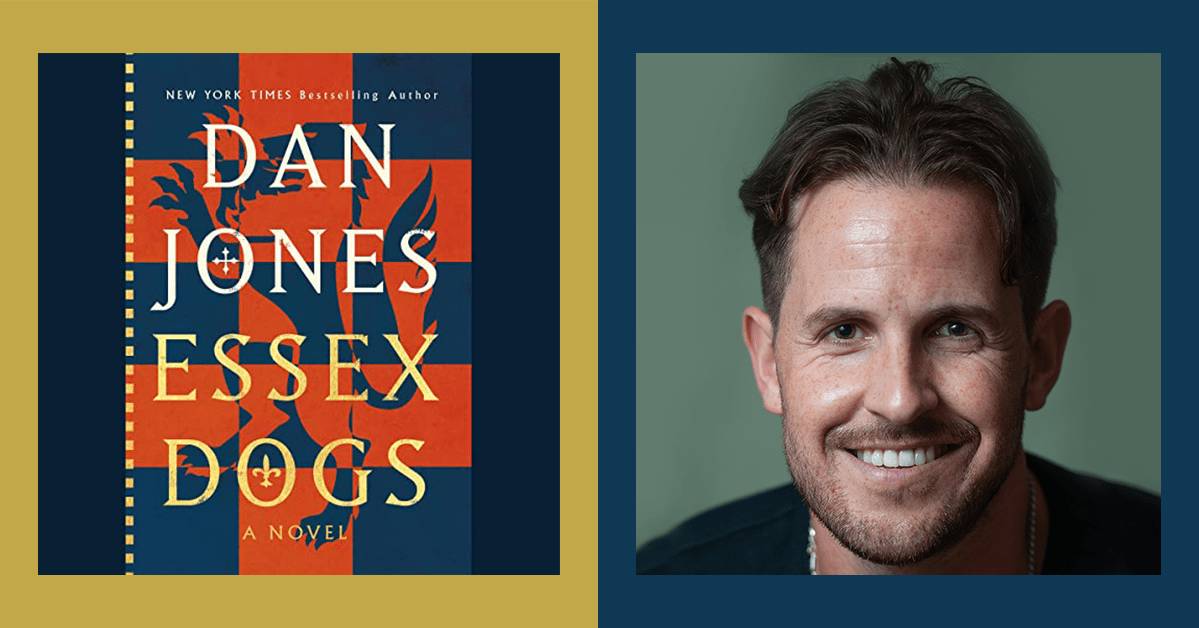

Katie O’Connor: Hi, listeners. I'm Audible Editor Katie O'Connor, and today I'm excited to be speaking with journalist, historian, and now novelist Dan Jones. Dan's debut historical fiction, Essex Dogs, performed by Ben Miles, follows an eclectic group of soldiers in the early days of the Hundred Years' War. Welcome, Dan.

Dan Jones: Thank you for having me.

KO: You are so loved for your nonfiction, books like The Templars and The War of the Roses. You make these historical explorations engaging and exciting and, frankly, feel like fiction. So why now? Why was now the right time for you to wade into historical fiction, and why this story in particular?

Add this interview to your Library:

DJ: Well, I think in terms of timing, it's really peculiar to my own psychology. When I agreed to do Essex Dogs, I had been asked in the past to do historical fiction for the reasons you've surmised. And I'd said no because I sort of didn't have a great idea that I wanted to pursue, but also because I was just very trepidatious about the whole process of moving from nonfiction into fiction, and frankly uncertain whether I'd be able to do it very well. But I got over that, I suppose, because I was turning 40 and because I'd written 10 big nonfiction books. And those two round numbers really just got into my head. And I decided if I didn't do it at this point, 10 books and 40 years old, it was going to kind of be a long wait before that superstitious round number thing came round again.

I also had an idea, which came to me in parts. It first came to me on a flight in 2017. I'd been working on a big drama project about the Templars, actually. It was around the time I was writing my book about the Templars. And I just had an idea as I was kind of dozing, dreaming on an airplane. I could see these group of three mercenary soldier types dragging a boat at the beach. I had no more than that to go on, but I opened my laptop. I made some notes about the characters. And it came very easily, surprisingly easily, because I hadn't really done many projects similar to that before. But I kind of didn't really know where to take it, and I was busy doing nonfiction books anyway, so I shelved it for a little while until New Year's Day 2019. I was in Normandy, France, and I'd taken a bunch of friends to Normandy to stay in a big, sort of tumble-down chateau near the town of Saint-Lô and not far from the Normandy beaches, famous from D-Day in World War II. And we took a walk on New Year's Day to sort of blow away the cobwebs of the night before and we were on Omaha Beach, and I don't know if you've been to Omaha Beach, I'm sure a lot of the listeners have been, it's a very moving place and you can't help but think of D-Day and the stories of World War II.

"I had dinner with George in the summer of 2019, and just the most fascinating conversation with him about history, and came away concluding that here was a man who just guzzled up history all his life and career and turned it into something amazingly entertaining..."

But, you know, this wasn't the first place that this huge amphibious landing to conquer Normandy came from England. This had happened almost 600 years previously, in 1346. Twelfth of July, 1346, Edward III landed 15,000 troops on the beaches of Saint-Vaast-la-Hougue, actually, which is near Utah Beach and Omaha Beach. But I started to think that this must've been similar in some ways in the 14th century, in the sort of later Middle Ages, as it would've been on D-Day in the Second World War. Not Messerschmitts, not barbed wire. Trebuchets, probably, and crossbow bolts. But the feeling for the individual, you know. If this is a World War II film, we're calling it The Grunts, right? Getting out of the boat, it's the beginning of Saving Private Ryan, only it's in the Middle Ages. And I put that together with the idea of this band which, by this stage, I was calling the Essex Dogs. And I thought, “This might work.” I took a little bit more time to sort of take the plunge and do it, but that was the genesis of the idea.

KO: I'm always really fascinated when you kind of get these kernels over the years and you just can't get rid of them, right? They stay with you until you finally give in and start to give it your attention. You said in an interview from several years ago that "historical fiction is the gateway drug to history."

DJ: Yeah.

KO: So, I was curious what type of gateway do you hope Essex Dogs serves as? Where do you want listeners to go from here?

DJ: Well, Essex Dogs, first and foremost, is the first book of a trilogy. There are going to be two more. In fact, I'm coming up on finishing the second one right now. It's called Wolves of Winter and follows continuous from the events of Essex Dogs. Essex Dogs deals with—

KO: Great title.

DJ: Thank you. Essex Dogs deals with the campaign, the seven-week campaign leading up to the Battle of Crécy. It's quite a linear story, but the trick of the novelist here was to branch it off in different directions to disguise where it was going somewhat. Wolves of Winter is about what followed next, which was an 11-month siege of the coastal town of Calais, which ended—this is not too much of a spoiler if anyone's even seen the Rodin sculpture—with Calais falling into English hands for 200 years. And that's a really fascinating story. So, many of the same characters move from one book to the next, but now they're not moving anywhere. They're just sitting outside the city trying to starve it out, and all around them are people who have an interest in this siege going on as long as possible. Wolves of Winter is kind of about the medieval deep state, money and the way that money is poured into warfare.

So, in immediate terms, I'm telling you read Essex Dogs because Wolves of Winter is coming pretty soon. But in terms of your point about historical fiction getting people into history, the history of the Hundred Years' War is something I've written about before in nonfiction in books like The Plantagenets. But it's a really fascinating entry point to a pivotal time in English and French history, the relationship between England and France, but also the broader relationships between the emerging nations of Western Europe. It takes us all the way up to Henry V, the Battle of Agincourt, and beyond, actually, but it spills off into Castilian history, into Portuguese history, into Scottish history, and so on. So, it's a really good way to get you into the sort of the drama, the chivalry, but also the sort of filth and the fury of the later Middle Ages and that classic time of knights on horseback and castles and sieges and derring-do. It's all there.

KO: Since you brought up that Essex Dogs is a trilogy, I wanted to hop over to ask you a little bit about your story planning. No spoilers, but Essex Dogs does end on a cliffhanger. And I was just curious how your planning, one, differed to when you write history, but two, did you find yourself plotting just for Book 1 at the start? Did you know that your cliffhanger was coming and you were plotting straight away across multiple books? How did that all kind of shake out for you at the start?

DJ: Well, I mentioned earlier on that even having had the idea for Essex Dogs, I needed a tip over the edge to get into doing it. That tip over the edge came from George R. R. Martin, one of the great fantasy—but I class him almost as a historical fiction author because he's so knowledgeable about history. I had dinner with George in the summer of 2019, and just the most fascinating conversation with him about history, and came away concluding that here was a man who just guzzled up history all his life and career and turned it into something amazingly entertaining, most famously Game of Thrones as it is on the television.

Anyway, one of the things that George said to me, which pertains to your question, was that there were two types of writer. There's the architect and the gardener. And I remember him saying this, and as he said it, I thought, "Well, it's obvious that the architect is the correct type of writer." Okay, because that's the kind of writer I am in nonfiction. I'm sitting in my office now. Over here, I'll show you. I know the listeners can't see, but you can now see that I have a planning wall which takes up a whole wall of my office where every book is mapped as though it is the architectural blueprint. It's mapped in fine detail. In nonfiction.

I wrote an outline for Essex Dogs. I wrote the first three chapters. I thought I knew what was going to happen in it, and I had a vague idea of the subject matter of Books 2 and 3. And I sat down to write it like a nonfiction book. I made a very detailed plan of the first sort of third of the book. I got excited. I started to write, and I just hit a wall. I just couldn't do it. I just found that nothing was ringing true, that I was just false-starting all the time. And I was not enjoying the process. And then I thought, "What did George say? Architects and what was the other one? Oh, he said gardeners." And he said that's the type of writer he was. He said, "You plant a seed and just let it grow and see what happens. And eventually, the characters will take over and start doing their own thing." I thought, "Well, that feels very terrifying to me." But there was a reason I chose to do fiction rather than nonfiction, you know? To learn as a writer, to grow, to improve, to experiment.

So, I'd started taking a very different approach to my [fiction], which was instead of muscling through an architectural plan was to kind of lie on the sofa a while or do some yoga or just kind of chillax, as they used to say, and let the story come to me instead of trying to impose order on material. And that was scary at first. Now, I really, really enjoy doing it. The characters really have taken their own will and their own independence.

What I do have, the benefit of historical fiction versus, I think, I imagine, I hypothesize, contemporary fiction, is that I do have beats I have to hit. You can't write a book about the Battle of Crécy without the Battle of Crécy. And you can't really write a book about the Battle of Crécy, as readers of Essex Dogs will discover and I hope enjoy, without reference to the great siege of [inaudible] or the crossing of the Blanchetaque, these almost miraculous crossings of rivers where the bridges had all been broken by the English army. Similarly, with the project I'm doing now, Wolves of Winter, you can't write about the Siege of Calais without the Rodin sculpture, which is the six burghers of Calais coming out with nooses round their necks at the end. So, this is helpful to me to have these historical beats to hit, and then the trick and the fun is to get there in a way that the reader who knows the history won't guess, and get from point to point through the history in an interesting, intriguing, and playful way. That, I found, is the structural process of the writing.

KO: So, is it fair to say that because you kind of knew that you had these historical beats to hit and were just thinking up creative ways to get from point A to point B, did you find that freeing when you were doing it with fiction? Sort of freed from that stress of knowing "Okay, I have to include all this XYZ," the way that you do when you're writing history? And if not, what were some of the other challenges that you found you were facing in fiction?

DJ: I found that it allowed me to have immense amounts of sneaky fun in fiction. So, at the beginning of each chapter of Essex Dogs, there's a short quote from an original source. And I wanted to maintain that link with a sense of groundedness in the sources between nonfiction and fiction. I was using sources which, had I been writing a nonfiction history of the Crécy campaign, I would have probably not used these sources, or the sources would've formed half a sentence, a sentence, a bare half paragraph.

I'll give you an example from the book. There's a fleeting reference in one of the original sources from the Crécy campaign that says the English army arrived at a town called Saint-Lô, and above the gates of Saint-Lô were the decapitated heads of three Norman knights who'd been considered traitors by the king of France, beheaded and their heads had been displayed above this gate. And these were retrieved. That's all we know, historically. We know who the heads belonged to, but we don't know how they were retrieved. Who got them? How did they get up there? This town was about to be sacked. Who was sent on this fool's mission to get some heads down?

Now, in a nonfiction rendering, it might not even be a sentence. It might be a footnote. I think I found it in a footnote of a secondary source somewhere. That's a whole chapter of Essex Dogs, because the Dogs get sent to get these heads. And not only is it wild how they get the heads, it's also a great illustration of a deeper theme of the book, which is the separation of understanding about the nature of war between the chivalrous knights—the officer class, let's call them, to use anachronistic language—and the vast majority of the rest of the army, the ordinary. In World War II films, you call them the grunts. Now, that disjuncture between those two views would be impossible to illustrate very well in nonfiction. But fiction allows you to do it with great sort of subtlety and cunning and mischief, and I think, then, allows me as a writer to say deeper things about medieval warfare, in particular, and warfare in general, but would seem out of place to me in a nonfiction book. So, there's a very different relationship with source material.

KO: I love that you found that from a footnote. I think that's great. But I am curious, since you're a historian, did you find yourself getting bogged down in research and ever have to say, "Okay, Dan. Time to stop. Get back to writing. You have enough. Let's go from here"?

DJ: No. I didn't. I never had that feeling because once the characters got going—so, the first bit of the book, to an extent, yes. Essex Dogs opens with this big scene. It is the beginning of Saving Private Ryan, it's just in the 14th century. It is deeply structurally based on the Atlantic magazine article “First Wave at Omaha Beach." And because the sources for the landing in the Middle Ages tell us nothing about the ordinary fighters' experience and because this was the genesis of the idea, I was like, "Okay, I need a structure here that's going to give it not only credibility in terms of the mechanics of getting off a boat and fighting on that beach, but is going to sort of deeply ping a listener and make them hear "My God, I haven't felt the Middle Ages sound like this before. What's going on here?"

"There was a reason I chose to do fiction rather than nonfiction, you know? To learn as a writer, to grow, to improve, to experiment."

I didn't find myself getting bogged down in research at all because once the characters were going, they really were doing their own thing, and it was just the case of sniffing out what's going to get these people excited? And the trick within the book, in terms of writerly craft, is to give you a vision of warfare that's locked extremely closely to individual characters. We have really two viewpoint characters, as listeners will quickly come to understand, in Essex Dogs: Loveday, the reluctant captain of the Dogs, and Romford, their newest member. And by the end of the book, we're flicking between them. By the middle of the book, we're flicking between them. And once you lock on to either of those characters, all you see of the battle, or whatever it may be, is their view of it. It creates a very chaotic and, for me, I hope, a sort of realistic vision of battle and warfare. But it also means that I don't need to know the exact troop movements at the Battle of Crécy. I just need to know what would it have looked like standing exactly here. And a lot of the job of the research is going, "Don't need to know. Don't need to know. Don't need to know. Go away, go away, go away." Whereas in nonfiction, it's the opposite. I need to know everything. I need to drink it in and then just spit out a tiny, tiny bit. A totally different process.

KO: Your style of storytelling was very immersive. It's really interesting what you did with point of view and how, in the beginning, it feels a lot broader and we're getting to know a lot of the Essex Dogs. And then you sort of narrow it more from there. I like your choice of chaotic. I think it did mirror what's happening with your characters. But I was curious if there was someone, and I have my own guesses, but who perhaps you felt most drawn to while writing.

DJ: I think what you might mean secretly is, who am I? Which one of these am I?

KO: [Laughs] No. I do want to know, though, too, if there is—there are some true historical figures present in Essex Dogs, but I was curious if any of your fictional characters, was there someone who you did base on someone in history even though you changed the name or the other details, that you're sort of like, "I want to throw this guy in, but I'm not going to tell you who he actually is"?

DJ: Okay, I'll answer your first question first, which is to do with my personal relationship with the characters. Loveday, for me, is the character that his sort of basic psychological predicament is probably closest to my own, which is he's about 40 years old and he's starting to experience the things that men at about the age of 40 often experience, which is just doubts about everything he's ever done and the sense of, not terror, because he sort of becomes more stoic as the story goes along, but of a creeping sense of horror at the futility, in both cosmic and in particular terms, of everything that's going on around him, and yet a sort of rising urge to protect the people he loves.

That, for me, is the sort of middle-aged man's predicament just sort of put into this interesting context of the 14th century. So, I felt naturally the most in common probably with Loveday, but then, you know, Romford is like a fiendish young man. And there are bits of myself and people I knew at the age that Romford is, friends I've had and friends that are no longer with us that had gone into him. But there are also, I just found inspiration for the characters in quite unlikely places. One of my favorite characters to write in the book is actually one of the nobles. It's the Earl of Northampton, William de Bohun, about whom I trusted that listeners would know vanishingly little, because I knew vanishingly little. And I don't think anyone's really a William de Bohun specialist, but maybe the five who will now send me Twitter messages.

KO: Right. I was like, "You're gonna hear from one listener."

DJ: That's a hostage to fortune. But he's the constable of the army and he sort of blunders into Essex Dogs about a third of the way through the story at a point when we've heard from one or two knightly, noble characters. And when Northampton came along, I thought, "I don't want a bungling idiot and I don't want another sort of wide-toothed, beautifully coiffured classic nobleman. I want someone who's a bit more salt of the earth." And William de Bohun became that. And my model for him, weirdly, was a soccer manager from the UK.

"The trick within the book, in terms of writerly craft, is to give you a vision of warfare that's locked extremely closely to individual characters."

I just remembered seeing something from when I was in my 20s. I'd seen a video of the soccer manager called Neil Warnock. Unless people listening to this are really into British football, by which I mean soccer, I don't think anyone's going to know who Neil Warnock is. But Neil Warnock was this coach. He was the manager of multiple different teams. And there's a video online, if you search “Neil Warnock dressing room,” you'll probably find it, of him going off at this failing football team in their language, in their profane, rough language. Even though he's the boss and they're the players, he's just got this way of cutting through and he says, "I love you guys," and he's, like, aggressively loving towards them. And I just was like, "I want this. I want this in the story." So, Neil Warnock, the football coach, just turned into this medieval earl who by the end of Essex Dogs, for me, is the only one of the sort of class of earls and knights and nobles who really is true and honest and a good guy. Even if his manner is just profane and he's rough and he can be cruel and he can be disrespectful, he's like, he's the only one who's kind of true.

So, Warnock as Northampton was a great one for me, but then there are some characters who are historical grotesques, and I'm very influenced in that by a non-medieval historical fiction writer, James Ellroy, the great American crime writer, and historical fiction writer, really. American Tabloid by James Ellroy about the Kennedy assassination is probably my favorite historical fiction book. What Ellroy does with Bobby Kennedy, Jimmy Hoffa, particularly J. Edgar Hoover in that book is just to play so fast and loose with these real historical characters. Makes them so compelling and so disgusting. I just felt that that was a part of historical fiction.

So, the best example [among my characters], I know you know what I'm going to say, is the Black Prince. Sixteen years old, given command, nominal command, of the vanguard, a third part of the army, by his father, the king. And he's just a disgrace. Now, it's funny if you know about the Black Prince because we know that in real history, this guy's going to turn out to be the sort of biggest name in knightly history of the 14th century and, like, lauded. If you go to Canterbury Cathedral now, you see his suit of arms and his tomb and “he's so wonderful.” Well, there's this little joke in there, which is like “How does this hero start off so badly?” This is Henry V on, well, not on steroids. On something else, as you will find out if you listen to Essex Dogs. But he's just as delinquent as the worst 16-year-old put in charge of an army could be. And I found a freedom to do that, particularly with the Black Prince at that age, at 16, because very, very little is known about him at that age that's not reflected back from his future glory. So, he's a quite a good character to play around with in that sense.

But equally, there are some minor characters who are—you know, Sir Denis of Moreton-in-the-Weald, he's just my favorite Peloton instructor. You know, I ride Peloton—

KO: [Laughs]

DJ: —every single morning, and Denis Moreton is like my favorite Peloton coach. And I just had this very buff—Denis Moreton used to have long hair in a ponytail. He's cut it all off now. And he's just funny. He's kind of strong. He's very capable and confident. He's got a gleam in his eye. You sense he's probably a bit naughty as well as being sort of very physically robust. So, Denis Moreton's just a knight who pops up in a little cameo role now and again, and I giggled away every time I was writing Sir Denis. Giggled away. I've never met or spoken to Denis Moreton, my favorite Peloton instructor. I don't know if he reads historical fiction. Denis, if you're listening to this, thank you for the many HIIT and Hills rides I've done. I'm sorry for making you a medieval knight. You know.

KO: Or you're welcome.

DJ: Or you're welcome. Denis, if you like historical fiction, you're very welcome.

KO: And the great British actor Ben Miles lends his talents to Essex Dogs and gives voice to all of these characters that you've been mentioning. You're no stranger to narrating yourself, having given voice to many of your histories. Did you have a specific vision in mind for the performance of Essex Dogs?

DJ: I did not because when I heard that Ben Miles was doing it, I was flabbergasted, frankly. Because Ben Miles is a god. And Ben Miles did Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel. For me, it felt like an extraordinary accolade, and I found it very flattering that Ben would consider reading this book. I have, as you say, read most of my nonfiction books. And I've enjoyed doing it. I didn't want to read my own fiction because I felt that it would benefit from a proper actor rather than just a sort of a doofus writer, you know? I know my limits as a reader, and I'm not a trained actor. And although I read my children like Enid Blyton Famous Five stories and they've got a variety of accents, I've only got about three in my locker, and one of those is very dodgy.

So, when I heard Ben's rendition of the book, he just got it, and he got the emotional pace of the book, because the book contains a lot of action. It contains some periods of intense boredom on the part of the characters who are trying to deal with the fact that they came to fight a war and when they first get there, there’s nobody to fight. But there is an emotional pace to the book which gathers. And Ben, I think, just really sensed that, and he really, really understands Loveday and Loveday's caution and his uncertainty in his own leadership and his sense of being bereft in many areas of his life, particularly from his wife and particularly from the Dogs' erstwhile leader, the captain. I couldn't be more thrilled that Ben did this, and I really, really hope we've got him contractually obliged to do the rest of the series, because he's fantastic.

KO: Fingers crossed. He does a wonderful job. I'm excited for our listeners to enjoy him. So, it sounds like your plate's pretty full. You have your Henry V nonfiction that you're working on. You have Wolves of Winter, [and] what will be Book 3 in your Essex Dogs trilogy. Is there anything else on the horizon for you that you want our listeners to know about?

DJ: I'm making a podcast called This Is History. I'm working on a TV show, which they'll do medieval torture stuff to me if I tell you about, but will soon enough be announced. I am always thinking of new ideas, and I've got a list of things I'm not contracted to write that I want to write which is terrifyingly long and looks like another sort of 10 to 15 years of career.

So, the moment I described to you that started this interview, about just seeing these guys dragging a boat up a beach that turns into Essex Dogs five years later, I keep having those moments, and my sort of hmm file on my computer is full of them. And the other day, I was like, "What is the great novel about the Spanish Armada? Hmm." Okay, so who knows? Maybe we'll be back here in five years' time talking about that, but then most likely not. But I do have this very big file of stuff I would like to do. And you just gotta be receptive to the kind of energy that tells you what it is you are going to do. I've got a series of 10 novels about the knight William Marshal. But 10 novels? Really? Are you really going to do that? I can't do everything all at once. I've lived like that for quite a long time, and I feel very fortunate that the well hasn't run dry. Do you know what I mean? I haven't woken up one day and gone, "Well, I think I've done everything I could think of. I think I'll become a landscape gardener." Not that I would mind that.

So, that's kind of my slate at the moment. My experience from certainly the last 10 to 12 years tells me that's only the things I know about, and some of the most fulfilling and enjoyable projects over the last decade or so for me have been the things when someone just rang me up one day and say, "Hey, do you fancy X?" "Hmm, yeah. Sure. Okay." And that ends up taking me off in another direction entirely.

KO: Well, you have plenty of listeners over here that will be ready for whatever does come out of that document of novel ideas. Ready to listen to it. And I think this concept of being receptive to creative energy, that's something I'm going to try and take with me into 2023 too. So, thank you for that, and thank you for your time today. I really appreciated getting to chat about Essex Dogs.

DJ: Well, it was so nice talking to you. And I can't tell you how thankful I am to you, but also to all the listeners, particularly in the US, where I know that medieval history, against all the odds, continues to thrill and excite people. So, I feel super blessed for that.

KO: And listeners, you can get Essex Dogs right now on Audible.