Note: Text has been edited and may not match audio exactly.

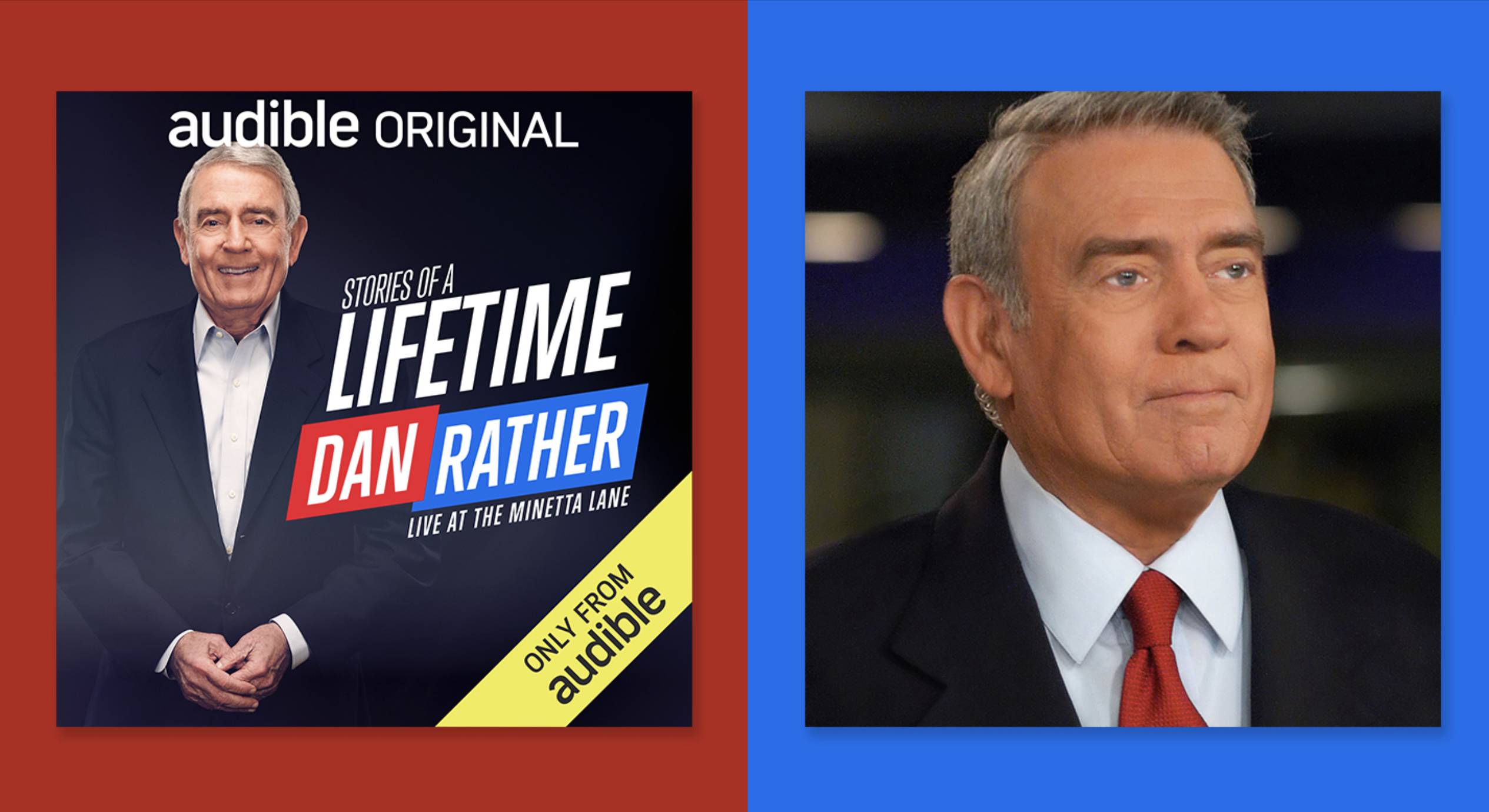

Abby West: Hi. I'm your Audible editor Abby West and today I have the honor of talking with Dan Rather, esteemed newsman, surprise social media darling, and star of the new Audible Original Dan Rather: Stories of a Lifetime. Welcome, Mr. Rather.

Dan Rather: Thank you very much. It's great to talk with you, Abby.

AW: You too. Why was this the right time and format for you to tell these stories?

DR: Well, in terms of being the right time, I never like to talk about age because, as they say, age is just a number, but I'm 88 years old and clearly on the back side of the mountain. I've found myself frequently thinking about another journey, the journey into eternity. Not to get morbid about it, but I thought it's either now or don't do it. I thought, perhaps, it would be, number one, informative to some people, and who knows, maybe if my humor comes out it might even be entertaining. That is the timing of it.

The format, frankly, is a format with which I'm very familiar, that as you know, having dreamed of being a reporter all my life, I started out being a war service reporter and then a newspaper reporter. But because I was a very poor speller, I got into radio. Radio is all about taking people to places, situations, mentally having them be there with you. I spent a good deal of time on radio before I got into television. So I'm familiar with trying to create word pictures in the minds of listeners. I knew the format would be comfortable for me...

Frankly, when we agreed to do it, somehow or other, I didn't realize we were going to actually do it in a theater over two nights and record it in the theater. Now, that created a certain amount of pressure. I'm not unaccustomed to a stage, literal stage, in that I had speaking engagements, but this kind of, if you will, performance theater, in an actual theater… let me say that I was a little nervous about that. But everybody at Audible was just terrific and we had two great evenings in which I was quite comfortable.

AW: I literally just got off the phone with our founder who was there that night and says it was a transformative 90 minutes for him. I assure you that the audio that's going out to the world is equally moving. You did a great job onstage, transforming from the career in front of the camera to being onstage and telling these emotional stories. You choked up over a few of them and not the least of which was in talking about your wife and the importance she played in your life, in your career, and your ability to have the kind of deeply ingrained career. Did you find that was rare? Your understanding and appreciation for the role of your wife in your life and your career was new or different from others for your time or the evolution of the understanding of that work-life balance and partnership of a marriage?

DR: Yes. The answer is yes to that. First of all, when you record in front of a theater audience, as we did for this, it is different from radio or any other kind of—without an audience. To make the point, in radio, you imagine the audience. I always try to imagine one person maybe driving their car, listening. That's where I sort of try to paint word pictures. But when you do it in the theater in front of an audience, it's a different dynamic. I've talked many times about my marriage to fighting heart Jeannie Grace Goebel Rather, the Princess of Pin Oak Creek. She, as is the case with myself, is a fifth- or sixth-generation Texan... I'm very proud of what she has done to hold the marriage together over 63 years and counting.

Particularly am I proud of the fact that Jean is, not only has she been a marvelous wife and mother and now grandmother, but she is a talented professional painter who's shown her paintings in New York, Los Angeles, around the world and is a very accomplished painter who mostly taught herself. My admiration for Jean knows no bounds. Depending on the situation and what I am thinking about at any given time, it's not unusual for me to get emotional about it because just about every good and decent thing that I have done as an adult—you might say that's a limited list, but nonetheless, every good and decent thing I've done as an adult primarily is because I married Jean. I will always like for her to get credit for that and to acknowledge that I know what a mess I was and I know what a mess I am and I know what a big job she had of holding things together.

My admiration for Jean knows no bounds... Every good and decent thing I've done as an adult primarily is because I married Jean.

As I say, it's not unusual, but I'd like to hold my emotions in when I can. I always took that attitude when I was an anchorman. I want to be a center, something steady and reliable, but I'm not a robot. After 9/11, who could go through the aftermath of 9/11 and completely, totally every second of every day, hold their emotions in? And so it is when I talk about Jean. We could spend the rest of this interview talking about her.

AW: I love that. That is one of the most romantic things you could ever say. That is wonderful.

DR: With Jean, one of the things we'd talk about in this production for Audible—people will hear the story—I was trying to tell people how I got to where I got, if you will, and a little bit of what happened when I got there. Maybe another time or during the later part of my career. It was an early stage. In attempting to explain to people that I had my ups and downs, I explained that I wanted to get engaged to a young woman with whom I'd known in college. I went to her father to ask for her hand. That's a little out of fashion these days but it was very much in fashion in Texas in the 1950s. This good and decent man was very gentle with me. He couldn't have been nicer but I tell the story of him basically saying, "No. I don't want you to marry my daughter, at least not now." Among other things, he wanted her to get an advanced degree in college, but also he was quite honest that he didn't think I could afford to get married and he was right about that.

The story has a good ending because she married someone else. Wonderful man. She's been married a long time, has children and, I think, grandchildren. She found a person who was just right for her, and because her father had been levelheaded and honest with me, I had later found Jean. That's one of those paths in life that I recount to the question of: What were your decisive moments? It was one of those decisive moments. The road untaken? Who can say, but I will say that I found Jean not too long after that. It was a break and her father did me and his daughter a great favor by leveling with me and telling me, "No for the moment, son. Maybe later."

AW: That's a theme. At least it's a theme for your career and life. Hard truths and facts and reality mingled with humanity. That's the legacy that you've left on-screen and with folks and it seems to have played through in your life as well. That combination of things.

DR: I appreciate you saying that. I really am. I'm grateful that you would say that about my so-called career. One of the things that I talk about in this Audible series that you and I are chatting about today is, I tried to make clear it hasn't always been the case. But as life went along, I learned the value of gratitude, humility, and modesty. How very important they are. And that early in my career when I was fighting to come up out of newspapers, radio, and early days in television, I made a lot of mistakes. It's not that I didn't make mistakes later. But then once I came to realize how grateful I should be and the value of humility—true humility, not the kind of false humility but true humility—and modesty, that I was, in many ways, a different person. I'm not saying I was a perfect person, but I was a better person than I was earlier on. I tried to make that clear and gave some examples.

AW: I love the way you did that. It was powerful to hear you talk about your wife telling you your head was getting too big early on and making you take a beat. That kind of vulnerability goes a long way for someone of your stature for so many of us. It's well appreciated.

DR: Thank you. As I say, the lesson came hard because… I do tell the story when I was first named to succeed Walter Cronkite as anchor and managing editor of the CBS Evening News. I tell the story of the first few years of that, in which, despite being told it was going to take a long time to really get an audience after Cronkite, we were successful and I got a big head. I tell the story of what it was like in our household for Jean, with two young children and a husband who had just been vaulted into the job of his dreams and was getting conceited and arrogant. Frankly, I think there were a lot of wives who would not have leveled with me. But Jean, she's always straight talking. She can be as blunt as a punt in the nose and she was that time about leveling with me. I tell the story of what happened in the wake of Jean saying, "Listen, you're very successful in this big, new job but you’re getting to be an unbearable person and we have to do something about that."

AW: Since you're both Texans, does she have the same sort of humor that you do? Does she have the little -isms that you have, as well?

DR: As a matter of fact, as for the Ratherisms, which we do talk about in this Audible series some, she understands the Ratherisms. She also understands that sometimes they need translating for people who do not speak Texanese. She doesn't mind them but, I would say, she's not a great fan of the Ratherisms. She's a pretty good editor. Sometimes I would try one out on her and she'd say, “Let me tell you... don't do that.”

AW: You give a lot of credit to a couple of teachers along the way who really helped steer you and the power of having those moments of people entering your life and helping to shape it. That was pretty powerful there, as well.

DR: I appreciate you raising that because I do talk about the difference that teachers, in general, have made for me and for my life. Several teachers specifically. Often, the realization of childhood dreams begins with a teacher. A teacher who cares, who understands your passion, understands how, while you’re dreaming, you have no idea how to reach that polar star of your dream out there and what a long, tough road it's going to be and what you need to do. I was very fortunate all through my time in public school. I went to public schools all the way through. Elementary school, middle school, what we called junior high school, and high school. Even college. I went to a small, what other people call a cow college. It's better than that. A whole lot better than that. A small teachers college, Sam Houston State Teachers College.

The power of a teacher telling you "You can do it" was, for me, I can't overstate what an impression it made on me and what a difference it made for me.

All the way through public school and elementary school, I can still name every teacher I had grades one through six and the principal because they were so caring. They were just terrific teachers. Now, this was at a public school in Houston, which has never been known as having a particularly outstanding public school system. Love Elementary School was in what was then called a tough part of town, what the sociologists would call a transition neighborhood. My elementary school teachers, they gave me all the education I was capable of absorbing. Then when I got to high school, my journalism teacher, Mrs. Williamson... you know, I thought I was a football player. I was a fairly good high school football player but I had it in my mind that I was going to be big star for the University of Texas or Texas A&M. She basically said, "Dan, the football dream? First of all, I don't think that you have a very good chance of achieving that." She had talked to my high school coach. Basically she said, "What your real dream, what’s your driving dream, is to be a journalist and you can do it."

Here's the point of taking you through on the story. The power of a teacher telling you "You can do it" was, for me, I can't overstate what an impression it made on me and what a difference it made for me. Then when I got to college, I met the legendary late Hugh Cunningham, who was the youngest professional at this little college, Sam Houston. And again, the power of his telling me, "You're talented and you have the passion. You can make it but you are going to have to work really, really hard." Then he made me work hard. Sometimes he would irritate me, but not anything to get angry with. He'd poured himself into my hopes and dreams. I'll give you an example. In my senior year of college—and I'd made good grades in college, partly because Professor Cunningham had put the whip to me, metaphorically—but before my senior year he said, "Dan, I put you down to take freshman English grammar." And I said, "What are you talking about, Professor? I'm a senior. I'm not taking it." He said, "Fine, but you're weak in grammar. You're weaker than you know and I can't, in good conscience, send you out to compete with your grammar being what it is."

So I took the grammar course when I was a senior. We diagrammed sentences, which you don't do anymore, but it was a way of teaching grammar, among other things. But that's an example. Then just before I was to leave college, or, well, as I was graduating, another professor who taught journalism some of the time—Cunningham was gone at this time—said to me as I was leaving, "Dan, I wish you good luck and with good luck, you can take it all the way." At the time, I didn't quite know what he was talking about. I didn't know what all the way was. I'm not sure he knew what all the way was. I think he thought I might become a big byline reporter for the Houston Chronicle. But again, time and again, his saying to me something positive, expressing confidence: “With a little luck, you can take it all the way.” Meant the world to me.

Too long, but with my experience with teachers, I believe so strongly in the power of the teacher who cares. I know personally what that power can be.

AW: You covered so many things throughout your career and so many important American history moments. Particularly, coming around the civil rights movement, you became emotional talking about the death of Medgar Evers. You had a relationship with Dr. King that was, as you put it, a more source and reporter relationship and then more of a personal relationship with Medgar Evers.... You also talked about even though you grew up in Texas, which was deeply segregated and had its own issues, you had never really witnessed the kind of violence that was really prevalent as you were covering. Was there a flashpoint during that time in your life that things either crystallized or changed in your understanding of the America you were covering?

DR: I go through this in our Audible series, of course. We talk about—I grew up in a Texas that was largely segregated. Texas had racist institutions including not just school segregation but segregation on just about every level. Water fountains. Restaurants. It was a deeply segregated society. It was not Mississippi, Alabama, or South Carolina but it had institutionalized racism and I grew up in that. But I had never personally witnessed racial violence, certainly not nearly as deep, as lethal, and as widespread as I was thrown into witnessing as soon as I started covering the civil rights movement. Covering the civil rights movement was my first big assignment for CBS News when I came to work for them at the end of 1961, moving into 1962.

Part of my job was to go to the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, day in and day out. One of Dr. King's followers and champions in Jackson, Mississippi, was Medgar Evers. A young man with a family, wife, and children, who was the epitome of what you hoped a civil rights activist would be. Not everybody can be the same but Medgar Evers, he always made a point to be well groomed, well dressed, well mannered. Very much a yes, sir and no, sir kind of person to all people. He was a fervent believer in the power of the ballot box and he’d dedicated a large part of his life to making it possible for most African Americans in Mississippi to actually vote. It's hard for people to imagine now because things are different, at least in terms of ability to vote.

In those days, all of Mississippi's white power structure was dedicated to keeping Black people from voting and they had all kinds of ways of doing it. I describe going with Medgar Evers once to a voting station where he had very, I wouldn't say frightened, but close to frightened African Americans with him who were eligible to vote, they paid their full taxes, everything. But the white person in charge just stood on the steps and told Medgar a version of “You ain't voting here today, you ain't voting here tomorrow, you ain't voting here anytime.” And Medgar Evers, who, hero is a noble word for him, but always a hero in my mind because he didn't flinch, he didn't back up, he didn't turn around. Stood there and in a very moderate tone of voice made the argument they’re qualified to vote, they have their material. He should let them in.

...Covering Dr. Martin Luther King and Medgar Evers and the civil rights movement of 1962 and '63 changed me as a person and changed me as a professional.

Of course, failing, because the power structure wouldn't let him in. I told that story in some detail. I do tell that story of Medgar Evers who, of course, was assassinated by a coward who hid in the weeds across from his house and shot him to death on the porch of his own home in front of his wife and children. It made such a deep impression on me, but that's just one of many anecdotes from that period which has led me to say, which is true, that covering Dr. Martin Luther King and Medgar Evers and the civil rights movement of 1962 and '63 changed me as a person and changed me as a professional. I had never seen a complex planned rally. By the time I got this coverage, after certainly a few months, I had seen two or three, maybe more. I had never seen police just yank someone out of line for their color, only for their color, and just beat them within an inch of their life. I had been raised in deep racism and I had not seen that kind of racial violence, and so all of that changed me in a deep and profound way.

AW: This leads into your new life as a social media darling. Something I'm sure you didn't expect.

DR: No, I didn't know and I'm not sure "darling" is it. I and we—I have a news company called News and Guts—we now have Twitter, Facebook, and then the news site is called newsandguts.com. This is all part of our social media and the internet. Now, when the internet first came into being, and particularly when social media first came into being, some young members of my staff, including Elliot Kirschner, who's been with me for a long time, came to me and said, "Dan, you need to hop on this horse that's Facebook and Twitter." I basically said, "You know, I was born too soon for this. It's all new, it's an evolving technology and I don't think so." They quickly came back and made the case and said, "Look, it's not an option. It's mandatory. It's imperative that if you want to matter, even in some small, infinitesimal, microscopic way, you have to be on the internet." So, rather reluctantly, I said, "Well, I'll try it but without any great expectations."

Now to my—certainly surprise, pausing to say perhaps astonishment—it has become by most measurements successful and by some measurements very successful. I have no explanation for it other than I know what I wanted to do. I thought, "Well, if I have anything to contribute, it is to try to use my experience—and yes, for that matter, the fact that I'd been in it a long time and I'd been a few places and seen a few things—to try to give context and perspective to what's happening today." How does it compare to 1968? How does it compare to the early civil rights movement? Trying to give context and perspective, historical perspective, and in so far as that, understand what success we've had, I think that's the reason it turned out that a fair number of people and, most surprising to me, a large number of young people are listening to that.

It's clearly one of those moments when we, as a people, as a society, as a nation, have a chance to make some big strides forward in the struggle against racism, in the struggle for more equal opportunity in the economy.

Again, I can't say that every time on social media we do that successfully and others won't have to judge how well or poorly we do it, if that's what we're trying to do. The deeper we get into this election year of 2020, frankly, the more our audience has grown because I do think that people ache to say, "Well, hey, put this in some kind of perspective. Will somebody calmly and steadily give us context of what's going on?"

AW: Given that you have that history, that lifelong experience, and have seen our culture and our politics have these different pulse points since the civil rights movement to the social justice movement of today, do you feel like you have a call to action for those who are listening and reading and following you?

DR: I don't put it in terms of call to action. That would be an editorial, to play journalism with you. We try not to editorialize. We do comment. However, if you put things in the proper context and perspective, which naturally we're always trying to do, I do think that when you see the demonstrations in the streets that we have seen, now as you and I are talking, for almost a month now, that is a call to action. It's not my call to action. It's clearly one of those moments when we, as a people, as a society, as a nation, have a chance to make some big strides forward in the struggle against racism, in the struggle for more equal opportunity in the economy. The opportunity is there. It was in the early 1960s when the civil rights movement that I covered in the early '60s resulted in the landmark civil rights legislation in the middle of the 1960s. The Equal Rights Amendment. The open housing and voting laws. Real progress was made. It didn't solve all our problems. We still had a long way to go. We still do. But real progress was made.

What you had was the movement, the civil rights movement, took a long time to gather momentum but once it gathered momentum, it was opening the real change. I think by any reasonable analysis, we have the opportunity for this to be one of those moments. What's especially encouraging to me is the diversity of those who are demonstrating. In the '60s, the antiwar movement was overwhelmingly white, and the protests, and, yes, in some cases riots in the wake of the assassination of Dr. King, were primarily African American. Today what we see in these... places, masses of people who are protesting. And there’s diversity of age, diversity of color, diversity of religion. It's tremendously more diverse.

I would say that I recognize that we… that I do think that not everybody who listens to this Audible production is going to love every word I say. I understand that. I do think that if someone listens, whatever their politics, whatever their ideological persuasion, there's an opportunity to learn. When I talk about the Vietnam War, covering the Vietnam War, talk about the people who fought the war, at least with those in the United States… what they feared, what they thought about, what they really thought about as opposed to what people thought. Again, I try to take you there. I try to take you to Vietnam. By the way, color was not an issue, by and large. The troops had a saying: "Same mud, same blood." In combat situations, all this stuff about the difference in races, the left or the right, I think people will come away with maybe some new dimension of war coverage.

The assassination of President Kennedy, which we talk about until this day... I try to take people there as well.

AW: I think you do an amazing job of taking people there. This is a fantastic listen. I remember being personally very disappointed I could not make the stage show, so I was personally happy that we were putting out the audio for the rest of the world to hear and I'm looking forward to the world getting to hear that, so thank you, Mr. Rather.

DR: Thank you, Abby. Thank you very much.