Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

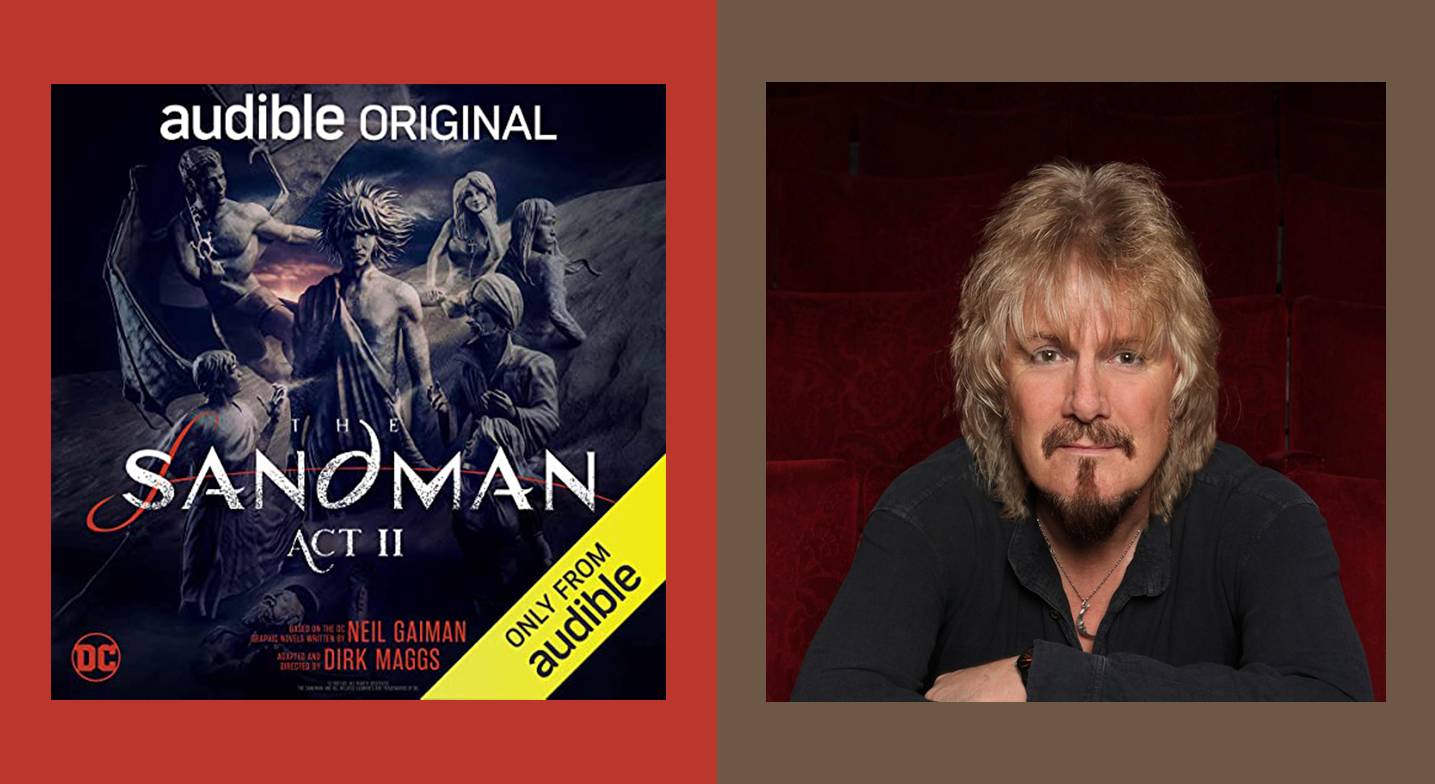

Reid Armbruster: Hi, this is Reid Armbruster, senior director of content marketing at Audible, and I am joined today by the inimitable Dirk Maggs, a multi-award-winning writer and director of fully immersive audio entertainment that fires the imagination. His groundbreaking audio movies have transported listeners to the worlds of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, Superman, Batman, Alien, and more.

Over the past decade, he has worked closely with his friend Neil Gaiman to adapt and direct prestige, full-cast audio productions of Gaiman's work, including Stardust, Neverwhere, and Good Omens, co-authored by Gaiman and Terry Pratchett. Dirk's latest collaboration with Neil Gaiman is The Sandman series for Audible, based on the seminal DC graphic novels. The first installment of the blockbuster series is a number-one New York Times audio bestseller, and the highly anticipated The Sandman: Act II is out right now. Dirk, welcome, and thanks so much for taking the time to speak with us today.

Dirk Maggs: Thank you, Reid. It's a real pleasure to talk.

RA: Did you always know that you wanted to work in audio? And what was the journey that brought you here?

DM: I originally wanted to become an actor, that was my big plan. I was going to be an actor, and because actors are not always in work, I thought I'd be clever about it and train to be a drama teacher. And my plan worked really well until I got to a college, which had a fabulously well-equipped theater and put on great productions, but also taught you to be teachers. And I discovered that I was a really terrible actor and I was an even worse teacher. Someone in the year above me got a job at the BBC, the British Broadcasting Corporation, in London. It wasn't the kind of place you could just walk into and get a job—or at least that's what we were told. Somehow I got in and I still don't know how. It seemed like a fluke.

Because I had some experience of making TV stuff at college, we started a TV service for the students, which was really fun. And we got up to all sorts of escapades, running cables across buildings at night and stuff like that. Against all odds we started this sort of TV service. And I think that kind of helped me get into the BBC. But the actual course I was going into was for radio. And I told everyone very confidently that within six months I wouldn't be having anything to do with this radio lark. It wasn't for me. I really wanted to make visual stuff.

But I did go into television and I did spend about a year and a half in TV, in BBC Television Center in London, and I really didn't enjoy it at all. It didn't seem to have the ease of creation that audio has, where you get somebody and a microphone and make a noise in the background, and you've created a scene almost immediately—the imagination takes over. The one thing I'd always enjoyed was comedy. I loved radio comedy. And the thing is, the UK still had a tradition of scripted audio entertainment, both comedy and plays.

The year I actually joined the BBC was the year that The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy was first broadcast by Douglas Adams, and this was the big groundbreaking entertainment thing. But my comedy exposure went back to my father, who loved radio comedy, and during World War II, when radio was king, would listen to his favorite comedy shows and so on. And I kind of got that from him. So the comedy department really appealed to me.

This Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy was something special, and so I applied for a job there and somehow got it. That was really where I began to work inside a production department. That was where I began to realize I could make audio sound kind of visual.

So I got into a department which was called "Light Entertainment," which, effectively was comedy, but they kind of had two strands to it. They did comedy programs, but they also did dramas, but not heavy-duty stuff. One of the program ideas that got me in there was a 50th birthday Superman tribute program—we staged this trial of Superman. He was on trial for adversely affecting the future of humanity, for interference in our affairs, kind of violating the prime directive if you will, if you're a Star Trek fan.

It was a chance to play with the idea of not only taking comic book characters but also inserting them into a sort of meta universe where you could have Lois Lane defending Superman and Lex Luthor prosecuting him. We actually kind of staged it in a large studio where we built the courtroom and staged the whole thing.

That was the point where I thought, "I would love to be able to dramatize some comic book material." And that's the point at which I thought, "Ah, you know what? It'd be really fun if we could make this sound like a movie, if we could mix it with really full, densely layered sound, and you hear the Foley, you hear the characters moving about, and their physical presence. And a music track and add a big kind of quasi-John Williams feel to this.

"What we're trying to do is make something like the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper, you keep listening because it draws you in."

As I was doing it, I was thinking, "Hmm, I think I've made a rod for my own back for the rest of my life here, if I carry on doing this kind of stuff." And I wasn't wrong. But at the same time it gave it such an immediacy and such a power—it really opened my eyes to what was possible. But while I was doing that kind of thing, I also, in the other side of the job, was making straightforward comedy shows and panel games and quiz shows. BBC Radio was very much of traditional radio comedy. And the sort of stuff you'd hear in the States in the '40s was still going in the '80s and '90s at the BBC. And I'm learning about comedy, I'm learning about writing, I'm editing really good comedy writers’ scripts. You very quickly pick up what works and what doesn't in that milieu.

Lesley, my wife, used to say it was the best evening entertainment in London, and it didn't cost anything, because tickets were free from the BBC. So, you know, I was having a lot of fun doing that, but this Superman thing, this idea of making stuff that I'm filming, was really the spark that had been engendered. Michael Green, who was the controller of BBC Radio 4 at that time, said, "Got any more ideas like that?" And I wasn't quite sure what he meant. So I said, "Well, we could do the Adventures of Superman." He said, "Great. Right. Jolly good. Yeah. I'll take six of those at 15 minutes each or whatever." And suddenly I'm in the business of making comic books into audio, which I don't object to in the least.

So we were able to make these things kind of against all odds. Sometimes it was really fun to come up with ideas for sound effects. We would rent a studio for a day and just do sound effects. I remember we took about an hour to figure out how to make Superman fly. We would try all sorts of whishes and noises, and it just sounded like comedy. In the end, I said, "What I really need is kind of a ‘shoooooo’ sound, like that." And I just, you know, wooshed across the mic with my mouth and that became a Superman sound effect, which, I might add, is being used in Sandman now.

RA: Nailed it.

DM: You know, this stuff really works. I remember I used to take popcorn lunches. I used to go out of the broadcasting house, walk down Regent Street to the cinema, and I'd watch movies and listen to the sound and listen to what they were doing. This was around the early '90s, so I went to see Terminator II, which, you can imagine, gave me loads of ideas.

So I tried to apply all those ideas, but it took a couple of years. And I think the turning point was when Douglas Adams heard what I was doing and got in touch with my boss. It just so happened Douglas had written what he said was the last Hitchhiker book. And he said to my boss, "So I'd love Hitchhikers to come back home to radio. There's this guy, Dirk Maggs, would he be interested?"

Douglas heard what I was doing and felt that there was something in it that reflected the sort of attitude he had towards his work in audio, which was to be as cutting edge as possible. He said he wanted it to sound like a rock album. And that's kind of how we're making Sandman. I don't tell people this because then they expect, you know, guitars and drums or whatever. What we're trying to do is make something like the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper, you keep listening because it draws you in. We very much quickly started to put together a plan to make Hitchhikers, which suddenly hit the buffers. So I was completely without anything to do. But then I sold the idea of going back to a Superman story. So we did the Superman Lives! storyline, which was the death [and return] of Superman.

RA: That's pretty cool.

DM: Yeah. And the fact that I'm talking to you about doing stuff 30 years ago, good God, yes, it is really 30 years ago, which is almost entirely an analog of what we're doing here on Sandman. It's the same deal, where we're going back to the mother lode and extracting all the goodness we can.

RA: What continually amazes me is your ability to record actors at different times, at different places, and then you make the interplay sound so authentic and seamless in the final audio. What's your approach to working with performers in the booth that allows that to happen?

DM: A lot of people think that the business of directing is to point at people and say, "You do this and you say that." But I find the more you trust the actors, the better it is. And, of course, coming up to date, when you trust people like James McAvoy, he's going to give you gold because this is an intelligent, very good actor.

I came in on this saying I was a lousy actor when I was at college, and so I realized I'd have to do something else. I think I've gotten better. And somewhere, if you put all the tapes together, I think I'm playing most of the key roles in this. Because if James is playing Morpheus, I'm reading in the other parts to him. And by doing that, I get used to how James plays things. So then I work with Kat [Dennings]and then I'm playing James to her Death. And then I'm working with Kristen [Schaal], and I'm playing James and Kat to her Delirium.

I'm not claiming any great acting skills for myself here, I'm joking. But I do think I've, over the years, learned to lock in my head how something is going to sound and how the characters work from each other. And also, the actors do listen to what we've done. James listened to Act I and got where we got Morpheus. Similarly, Kat really knows what we've done with Death now. So they're comfortable in the roles. And I think it's kind of like you know what it's going to do. If you add H2O to bicarbonate of soda, it will fizz — you know, that sort of thing. I'm not a chemist, but I think that's what it is. They know what to expect.

And then getting Kristen in, because I know how James and Kat will do what they do, I can kind of aim that at Kristen. And then she, who is a really good actress, she comes back with a performance that blends with that and so on. I don't think we've had any occasions when a remote-recorded member of the cast hasn't sensed where to place the ball. It's like a tennis match really. How to guarantee return of serve kind of thing, and that really is down to them, A, being professionals, B, being intelligent, because the really successful actors generally are very, very bright people. They're intelligent, they think.

And of course, a lot of them are big fans of Sandman because that's the power of Gaiman. They're big, big Neil fans and so that really helps.

RA: Speaking of the power of Gaiman, it was through Douglas Adams and Hitchhikers that you and Neil actually met, was it not?

DM: Yeah, pretty much. Douglas was a mentor to both of us because when Neil was a journalist for New Musical Express, one of the music papers, he was writing a biography of Douglas and they got to be pals, and Douglas encouraged his ambitions to be a writer. And similarly, Douglas kind of talent-spotted me as an audio producer and encouraged me. So we separately were on separate tracks. And then what happened was I got friendly with a wonderful lady called Phyllis Hume, at DC Comics, when it was in New York — a wonderful Brooklyn girl. Just totally killer New York sense of humor, just cut your legs off, you know? She used to ring and say, "Have you read this? Have you?"

Because we were doing the Supermans and the Batmans, we got to be friends. But she said one time, "Do you know a guy called Neil Gaiman?" And I said, "Well, you know, there are several million people in the United Kingdom, like, it's not possible I've met all of them." And she said, "He's brilliant, he's a genius, he's this, he's that. And have you read The Sandman?" And I'm starting to read this stuff and I'm thinking, "Oh my God. This person is completely reinventing everything. He's inventing a whole mythology and then packing it with all the other mythologies." This person has a brain the size of the planet, and I just was totally gobsmacked, as we say. I just thought, "We've gotta do this." I wanted to do something that employed all these movie-like sound techniques but at the same time was really artistically new. I tried to pitch it several times and I got in touch with Neil, and we were emailing each other in the early '90s.

RA: So you and Neil, ostensibly, were talking about bringing The Sandman to audio 30 years ago?

DM: Yes.

RA: And here we are and it's finally happening.

DM: Yes. Luckily we're still upright.

RA: I think it's happening in a very big way and very successfully, which is wonderful. Which brings me to the point that many doubters said The Sandman would never work in audio or could never work in audio, given that comics are such a visual medium and this particular comic series is so dense and so literate. And then you've got the added pressure of the comics being beloved by so many when you finally get get this opportunity. Fast-forward to #1 New York Times audio bestseller status and praise from newbies and diehard Sandman fans alike. How did you pull it off? What was your approach to the adaptation and why do you think it has been so successful?

DM: Well, I had been thinking about it for 30 years with Neil, so that helped. But at the same time, I knew it was going to be a challenge, because Neil's work is so beloved by its readership that you really have to tread lightly and be very careful. In many ways that meant that I didn't want to wander too far away from the original text. For example, if we were doing Oliver Twist, I personally wouldn't choose to update that '60s London, because, basically, a lot of the bits don't work. So Sandman was '89 to '95, let's say—roughly it was the time period that I was going to stick to.

For example, if you give Rose Walker a mobile phone, she's probably not going to have a problem with Fun Land for too long in that hotel room. Once you introduce modern elements, you're changing how the story is told. So having decided to do that, I've got a bit of a problem because I'm used to taking an idea and running a bit with it, you know? I felt I had only a limited amount of massage room on Sandman because it was so precious to so many people.

So how can I make it something that would still surprise and delight people who thought they knew it backwards? And the obvious thing to do was to ask Neil for his original scripts, which are the scripts the writer of a comic gives to the artists, letters and inkers, and colorists to create the final thing. They are kind of like film scripts. They explain the action, they give an idea to the look of the thing, and so on. That seemed to me like a really good idea.

When I do have Neil scripts, not only do I have all the information I need to make sure I don't miss stuff, but I've got his descriptions of people, places, of action, of what is the undercurrent underpinning the sense of this, all written by Neil. And because he's losing himself in the world, written in a very poetic kind of way, I think it's not unfair to say Neil is a bit of a poet on the quiet. In fact, there are whole sections of Sandman which are actually written in poetry, or iambic pentameter.

Neil just rhymes, what he does rhymes. And so, by taking his descriptions of people and situations and so on and so forth you have a narrator role opening up where you can place the action, you can describe the characters, you can ascribe certain motives to what's going on.

That was the first big turning point—finding that, knowing that we could then go into Sandman and the listener would be taken by the hand, by a narrator, and walked through it. And the next thing that happened that really made that work, was when Neil emailed, saying, "Would you mind awfully if I was narrator or do you have someone better in mind?" And it's like, "Um, define better?" [Laughs]

He kills me. Because, you know, who else but? Who else but? Anyway, so I said, "No, I think we'll have them put up with you." And, of course, Neil has just this totally Neil delivery on things. So we end up kind of rewriting stuff as we go. But that was the thing. We're digging even deeper into the mother lode, which is the original scripts. We've got Neil himself narrating, as if we're back in the room with him when he's writing it and these ideas are occurring to him. We're kind of sitting on his shoulders, seeing him being seized with an idea, which is a wonderful thing. It's really great to watch him work, because he's quite possessed by himself, if that's not a weird thing to say, when he's reading this stuff. And you can hear it in the read. There's some wonderful moments.

RA: Let's talk about The Sandman: Act II. Were there any lessons learned from the first installment that informed your approach? And given that you're an innovator by nature, did you try any new things with Act II?

DM: Yeah. God, that's a good question. We’d just finished Act I and it was going down really, really well. And it was so intense an experience that I had to do something very profound. So I ripped my office out at home and remodeled it during the first two months. That was the first thing Act I gave me—a remodeled office. It nearly gave me an ulcer. It seemed pretty likely we were going to do Act II, and then we thought, "Well, if we do Act II, why don't we do Act II and III back to back?" Because certain story arcs run across them. Orpheus, for example. We planned an Act II, we got an Act III, and so on.

So that was kind of an idea that I regretted later when I realized that I'd bitten off a little more than I could chew. However, I am still here chewing. I think the thing about Act II is, at this point in the books, Neil has really hit form, he's in his stride.

RA: I’ll say.

DM: Season of Mists is a killer of a story, it's so cleverly done. It's so clever. And that meant that I knew we were strong in terms of story. I knew that we were going to have a fantastic cast because our casting team, led by Mariele Runacre-Temple, are fantastic. What I had to do was try and generate a script that really worked for it. And that was the tough part because we were kind of squeezed on time, and I was sending out first drafts of the script. And the script at this point is interesting because Neil's descriptions to artists have become more truncated and more abbreviated because the artists now know what they're working with. So that means I have to add a little bit more of Neil-isms into the process, and that was a bit of a learning curve.

So by the time we get to Act III, I'm feeling much more confident about how the script is coming together. Act II ends up really great because Neil kind of co-writes his narrations with me in the studio. And we end up with this sort of best of both worlds. I'm thinking of how it's going to sound, he's thinking of how it reads, and we really blend nicely. The one thing that I really wanted to change off of Act I, was to use a bigger studio. Because we actually had a studio, which was something like, let's say, optimistically, 15 feet by eight. And that's fine if you've only got one or two or maybe five readers in, but when you're doing a Midsummer Night’s Dream with 15 actors in there, it is like a sauna with no pleasant fumes from water on the hot coals. And so, this time around on Act II, we were able to work in a big studio. And of course, at that point, COVID had really hit. So the timing couldn't be better because the bigger studio meant that we could actually use partitioned-off areas where the actors could work, but it did give us a chance to have the actors working face-to-face. One of the things about this business is that, even though there's no wardrobe, there's no makeup, there's no set as such, actors work really well when they have eye contact. Whenever people ask me about recording actors in a studio, I always say, "Try and get them facing each other so they can see each other. Because if they make eye contact, they will act at each other." So those were improvements. But I think the real thing about Act II is, we all learned a little bit about how it works. We all found elements that really paid off.

"I'm thinking of how it's going to sound, he's thinking of how it reads, and we really blend nicely."

One of the biggest single things is Jim Hannigan's music, which is just unbelievably beautiful and romantic and sweeping and huge. It is the heart and soul of the piece, you know? We pour in everything we know to the acting, to the sound design, to the mixing, and then Jim comes along and adds a music cue and it just punches you right in the heart. By the time we've finished mixing Act II, I'm thinking, "Yeah. This is exactly where it needs to be and very much what we had thought of doing 30 years ago. I think we've hit form. I shouldn't say this, but I think it's not only better than Act I, I think it's the best thing I've ever done in my whole career.

RA: It's quite a legacy that you're leaving. It's a true labor of love. As a creator, how do you know when your work is done? Because I know you like to iterate.

DM: How do you know when it's done? That's a very good question. One thing that always makes me laugh is that if Douglas had been around for when we were making the last three series of Hitchhikers, I'd probably still be mixing 'em, because Douglas could never not be tinkering with it. We'd never get the thing released. So you do have to choose a point at which it's finished. That said, for Act I of Sandman I did a ninth mix of the whole thing the day before it was released. The fact was that it wasn't done and it still isn't done. I still listen and there's something I'll cringe at, tiny things, little things nobody hears but I hear. So, nothing's ever done.

RA: What do you think people would say are the hallmarks of your work—your unique thumbprint?

DM: What I do is dense but transparent, that's what I aim at. Something that has loads of layers from the background to the very foreground. And sometimes in front of the foreground, you know, where the character is, you're hearing the cloth moving. So it’s the Foley that we do, right down to the background and the music and so on.

I like to try and make it as rich and as dense as I can, and then make it so that you don't miss a single thing that's in that picture. And that is the skill I've tried over the years to develop. That and keeping the story moving in such a way that you're not aware that your ears are being manipulated like that.

It's actually organizing information. Really what I'm like is like a traffic cop. I've got a story to tell, I've got a load of sound effects, I've got a load of backgrounds, I've got Jim's music, I've got actors saying lines. And quite often I will write a script where one actor is saying lines over another actor in the background saying other lines. The trick is to be able to make it so the background actors' lines—when there's a silence in the foreground actors' lines—pop up and something meaningful happens that you realize they're talking about something and you're getting the gist of where that's going. And all of this presented in such a way it's like the sugar on the pill.

What I love is when people say, "I can't believe it works in audio. I never thought an audiobook of a comic could work for The Sandman or whatever it is." And I'm thinking, in the end, a storyteller is disseminating a measured amount of information on a comic book page, book page, a movie script. We're doing it in audio. And what you have to do is do it in such a way that you're not wasting their time, you're keeping them engaged, and they're not missing anything as it goes by.

Particularly in audio, because you can wind back, but it's pretty hard to do. It's not like turning back in a book where you can turn back a page. So we kind of have to hit you the first time. If anything I've learned over the years, it's how to do that.

RA: What is so special about audio as a medium? What have you discovered about it over the years? What keeps you engaged with it and excited about it? And what do you think its future holds?

DM: Audio kind of lost its way for a bit over the years. In terms of the world, I think BBC kind of still was in there and that's where I learned my trade and I love the BBC dearly. But it's like you love your old school, you think about it and there's so much you love about it. And then you think about the detail and think, "Oh boy, I really didn't like that part." But on the whole, the BBC was a wonderful thing and it had carried on that tradition. I think it was the creative freedom.

"An audio studio is a kind of blank canvas on which you can paint anything."

You know, I grew up in the 1960s and the Beatles were happening, and it was magical. It was magical. The Beatles, the Stones, the Kinks, all of that British music was happening and the great stuff over in the US with all the fabulous bands at that time, the Byrds and Creedence.

But here's the thing. If you go into Abbey Road Studio 2, where the Beatles recorded all their hits, which is still a working studio, and you're in the room where they did Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, which was at the time, a sort of Technicolor explosion of what is possible in sound. And you walk into this really rather indifferent, large hall with a worn wooden parquet flooring, nothing has changed.

You walk in this room and it's not depressing or anything, but it's really a working space. It's got nothing. It's not like studios nowadays, which are all beautifully polished wood and what have you; it's a real hall. It's like a parish hall in England. It's just nothing. And all this magic came out of that place, because it's all in the pure imagination. These four guys and a bunch of instruments, make this magic happen.

An audio studio is a kind of blank canvas on which you can paint anything. But the thing is, all the painting is done in your imagination and everything you're doing in there, you have to filter through your imagination in order to know whether or not it's headed in a direction you want to go. There's a kind of complicity between the people working in an audio studio, which, in television, let's say, I found lacking, because it had to be physically there to be represented.

Audio just immediately did away with this tyranny of the image where it has to be literally there to tell you something. I love the fact that it doesn't tell you what to think. It lets you think whatever you want to think. The movie is in your head and it's your imagination that is the key and the lock of Sandman. It always was when you read it, and it is now when you listen to it. And that for me is where audio is a magical art form. And I think it's flourishing now, thanks to the internet.

This medium isn't going away at all, it's coming back. Anytime you get behind a wheel of your car and you want to drive two states, what are you going to do? If you can't watch a movie, you put on The Sandman. It's made for the world we live in, and you can get the ironing done. There's so many things you can do.

RA: So, Dirk, tell us what you're working on now.

DM: Booking a vacation, Reid. [Laughs] At the moment, Reid, I'm working on The Sandman: Act III, because Sandman and Neil Gaiman waits for no man. We are in studio and it's very exciting because we get to carry on the stories and the characters that we know and love. So that's fantastic. That will take me into the New Year, which is very jolly. So I'm a happy bunny.

RA: As always, it has been an absolute pleasure, and thanks so much for taking the time to talk about all things audio movies, and especially about The Sandman: Act II, available now only on Audible.