When we first meet, Michael Silverblatt wants to tell me about a book. This fact in itself is not unusual; he is one of the few people in Los Angeles who makes a living doing this very thing.

Bookworm, the weekly half-hour interview show that Silverblatt has hosted for Santa Monica’s KCRW-FM for more than twenty-five years, recently welcomed returning guests such as Jonathan Franzen, Mary Karr, and Salman Rushdie, and he was about to record a special session with David Remnick and Deborah Treisman of The New Yorker, two of the most powerful gatekeepers in American fiction.

But on a February afternoon, Silverblatt is thinking ahead to the AWP (Association of Writers & Writing Programs) Conference, which will be coming to L.A. in the spring, and promises to bring with it a wide array of underappreciated authors who don’t often visit the West Coast.

One of them is John Keene of Jersey City. Keene was a member of the Dark Room Collective, an influential group of African-American poets, and teaches writing at Rutgers-Newark, but has published only two works of fiction in 20 years. I had never heard of him.

Keene’s book Counternarratives, the one Silverblatt wants to tell me about, was released by the New York-based small press New Directions a full year ago, and though it received universally glowing reviews, the book was obscure enough to escape the notice of, say, the New York Times Book Review. Silverblatt sees a chance to introduce the veteran writer to a wider public. “When I discover a book I want to put it on the map,” he tells me. “But the map is resistant.”

“I’m not interested in having someone say what they’ve said on other shows … I want to hear things I haven’t heard before.”

As his longtime platform for bringing his favorite authors to the ears of the public, Bookworm has a pretty simple format. It is not an elaborate production. There are few moving parts — usually two people and a book — and it isn’t a live broadcast. But the preparation for a single show can take months, even years, because Silverblatt makes a habit of reading not just the book in question, but the entire catalog of the author he’s hosting. And he doesn’t read the way other people read.

“I believe that your first reading of the book is your introduction to the book,” he says. “The second reading is the first reading. The third reading is the dream come true where you’re so familiar with the book that it’s like hearing from a friend, that you, by now, really can read this book with depth, with passion, with an understanding that the first time you read it, you were often misunderstanding the intention of the writer. You were seeing the battleground but not the sides. The forest for the trees is the usual metaphor.”

Because he operates without a list of prepared questions, he aims to develop the fullest possible sense of a writer’s project before entering the studio. This preliminary research is Silverblatt’s way of earning his seat at the table, of justifying his place in conversation with the people he takes to be the most intelligent minds of our time.

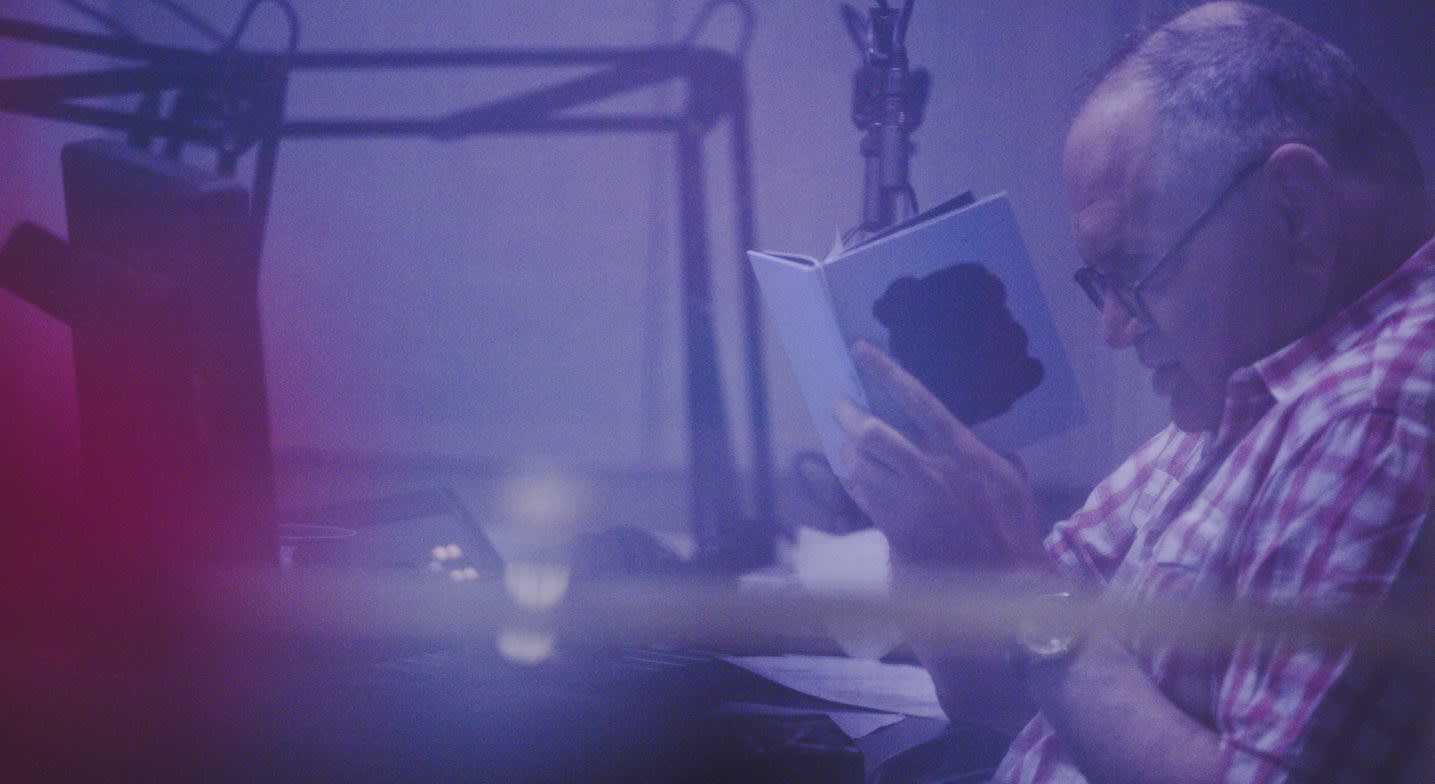

Bookworm host Michael Silverblatt in his Los Angeles home.

Silverblatt sees himself as a kind of audience surrogate, doing the deep reading his listeners would do if given the time and opportunity. “Do I really think that my listeners are going to read a book three times? No. I don’t at all,” he says. But “I think it’s important to expose them to the idea that that is the way in which a book is understood over time in a culture, and [the way] that books live.”

The Bookworm is a tall, bespectacled man in his early sixties who wears sneakers with button-down shirts. You will often find him with his nose in a book — almost literally. Because he’s cross-eyed, he can’t read a text unless it’s pressed up against his face.

But visual identification may be unnecessary. If you know him, you know him by his voice. Hushed, unhurried, and difficult to interrupt — but also convivial, gentle, enchanting — Silverblatt sounds like someone taking pleasure in puzzling his way through a labyrinth, inviting you to help him find the exit.

The sound of his voice is an inescapable component of Bookworm, because its host generally speaks as much as his guest. Though his home station is an affiliate of NPR, whose anchors are distinguished by their just-the-facts disinterest, he makes no attempt to be neutral or impartial — and prefers an emotionally charged reading to a dryly intellectual one. (In an interview with Stephen Dixon from 1995, you can even hear the host cry.) He is intensely engaged without being confrontational, and restricts his area of interest to the world of the books themselves. He does not discuss politics or, say, the author’s difficult childhood. A Silverblatt question is usually astute but not exactly sharp, and it often emerges over the course of an extended set of musings.

Listening to Bookworm means contending with (or luxuriating in) the fullness of Silverblatt’s response to the book, a response that he often presents to the writer for unpacking — or approval. “Am I overreading?” he asked, in a recent conversation with Don DeLillo. (DeLillo said no.) The fragility of Silverblatt’s voice projects a kind of perpetual concern — for his guests’ comfort, for his audience’s understanding and support, but also for the future of reading.

Silverblatt is earnest, so he is easy to caricature. He appeared as a version of himself in the indie comedy Ruby Sparks, and a pretentious Silverblattian interviewer showed up in a recent episode of the L.A. sitcom You’re The Worst. He is most endearingly parodied on Parks and Recreation, where Dan Castellaneta plays the host of “Thoughts for Your Thoughts,” asking Amy Poehler questions like: “Could one say that a book is nothing more than a painting of words which are the notes on a tapestry of the greatest film ever sculpted?”

His persona risks self-seriousness, with a sincerity that strikes some as cloying. His guests can sometimes seem unprepared for his ardor, or puzzled by his train of thought.

But those who are serious about the vocation come to respect Silverblatt’s approach. The brilliant short-story writer and novelist Lorrie Moore, who seems to avoid the press when she can help it, makes time for Bookworm during each publishing cycle. In an email, she wrote, “Michael always has read the book (this shouldn’t be unusual but often is) and has a good memory for it. He often comes at things from a very personal reading, or an unexpected angle, but that is fine and often more interesting than the usual journalistic responses.”

By asking questions that feel rooted in genuine, well-informed curiosity, Silverblatt avoids eliciting well-rehearsed answers. Contemporary writers are not typically used to speaking to a media figure who takes books so seriously. “I’m not interested in having someone say what they’ve said on other shows,” Silverblatt says. “I want to hear things I haven’t heard before. I want … the excitement that an author feels at speaking to someone who’s really read the book as opposed to someone who’s filling a seven-minute segment.”

Unlike his college friend Terry Gross, who speaks to her Fresh Air subjects remotely from the WHYY studio in Philadelphia, Silverblatt insists on an in-person encounter. “I believe in meeting someone’s eyes,” he says. “I think it changes the way they talk. When you’re looking face-to-face, first of all, the sentences get more complicated. When you break the eye contact, you notice … the sentence ends. I’m trying to let people hear the drama of the passion and the excitement and illumination that comes when two people come to an understanding of one another. When you talk to people on the phone, they can be easily disengaged or start drinking. You can hear ice cubes rattling on a tape I once did with Toni Morrison.”

In the dim cocoon of his KCRW studio, the host has a way of shepherding writers through emotionally difficult material. Lorrie Moore says she never prepares for interviews, but “I think it would be especially difficult to prepare for Bookworm.” Near the end of their most recent recorded conversation, Silverblatt asked her, “Is there a way in which writing a story can be a cure … for misery, or is misery just a given?” After Moore addressed his inquiry with an appropriate level of introspection, Silverblatt seemed touched, and said, “Thank you for your emotional availability today.”

Silverblatt is not a critic, but an enthusiast with a platform; Bookworm generally only features books he likes. In the best of the Bookworm conversations, one senses the guest’s gratitude at communing with such an intensely attentive and sympathetic reader who removes the book from the sphere of evaluation. “I feel like I want to ask you to adopt me,” David Foster Wallace said, in the first of their three interviews. Norman Mailer simply called him “the best reader in America.”

Silverblatt doesn’t think there’s anything precious about cultivating a safe space for conversation. “When I was in New York, I listened to Lenny Lopate a lot, and he wants to fight. He’s a bulldog. While I think Lenny is really smart, it’s not my kind of thing. I say to my guest, please don’t be nervous. I don’t have people on the show if I don’t like the book or something about it. Am I going to love 52 books a year? Highly doubtful, but there’ll be something I like about the book, something I think is important.”

For many listeners, myself included, the reliable pleasure of Bookworm comes from the astonishing weekly realization that the culture has made space for at least one person to fully devote himself to the task of reading deeply. Silverblatt sees the show as “a place for the exposure of beautiful ideas,” whose audience includes “those of us who are trying to be nurtured by the lives we lead [and] not just trying to get more stuff. We’re trying, I believe, to find a place where a word like ‘soul’ is a meaningful term to use in a conversation.”

The world does what it can to accommodate Silverblatt’s pursuit. In a time of diminished resources for arts coverage, his life and work is made possible through the largesse of the Lannan Foundation, which underwrites Bookworm — and makes it affordable for KCRW. (For the first five and a half years of Bookworm, Silverblatt did the show for free, as a kind of public service.) The first time I meet him, he invites me to one of the L.A.’s most critically acclaimed restaurants, an upmarket trattoria near his home. We are seated at his preferred corner table, and instead of a menu, the chef presents us with an over-the-top delicious seven-course meal customized to allow Silverblatt, a diabetic, to manage his blood sugar. When the bill arrives, the price is arbitrary — and affordable.

The idea was to maintain one dwelling for himself and one for his books

An unlikely Angeleno who long ago left New York hoping to make it as a screenwriter, the Bookworm does not drive, and for decades has depended on the kindness of strangers to navigate the city. And because he’s too busy reading to learn how to cook, he’s known by name at seemingly every decent restaurant within walking distance of his home.

Silverblatt, who lives alone, rents two units in an apartment building in the Fairfax district. The idea was to maintain one dwelling for himself and one for his books, but over the years, his alphabetized personal library—which reaches from floor to ceiling—has spilled over into his living quarters. (Shelves A through S still live downstairs.) His assistant also lives in the building, and they initially bonded over a shared affection for Thomas Berger’s Little Big Man.

He prefers phone to email, still refers to “the web,” and will ask you to print out any article you want him to read. Yet he remains intensely curious about the ways that the literary imagination is meeting the demands of the internet era. Last year, he brought on millennial provocateurs Mira Gonzalez and Tao Lin to talk about their compendium Selected Tweets. When he asked them where the “soul” was in their work, “they didn’t know what I was talking about. They’re in a different realm. But that’s interesting to hear, too.”

He has no use for e-books or audiobooks, but finds no fault with any technology that enables people to maintain a relationship to literature. “What I want them to do is to participate in the idea that culture is still living. It doesn’t matter if you’re reading something between covers or on a screen. If you’re reading, you’re taking part in the dialogue, and that’s of tremendous importance.”

It’s a gorgeous April day when John Keene arrives on the Santa Monica College campus for his Bookworm taping, but no sunlight intrudes upon the busy basement headquarters of KCRW. He has arrived with his publicist and his partner, both of whom made the trip with him from the East Coast.

Keene isn’t here to promote his book, exactly; he knows thatCounternarratives isn’t easy reading. It’s an intricate and highly allusive collection of short fiction, whose stories include “An Outtake From the Ideological Origins of the American Revolution” and “Gloss on A History of Roman Catholics in the Early American Republic, 1790-1825; Or the Strange History of Our Lady of the Sorrows,” the latter of which is presented as a seventy-five page footnote to another unseen text. Keene’s ambitions are grand; the collection spans several centuries while reimagining and reclaiming various forms of literature concerned with the African diaspora. The stories are written to resemble slave narratives, journal entries, and pages from history books, but are dominated by frightening ghost stories, witchcraft, and strange, obsessive voices.

When Keene enters the sound booth to meet his interlocutor, there is almost no preamble. Silverblatt, who has spread out in front of him not just copies of Keene’s books, but also Jean Toomer’s Cane, a famously enigmatic short-story cycle written during the Harlem Renaissance era, immediately starts talking to the author about literary history and the diverse set of influences that weave their way through Counternarratives. Keene quickly gets on his wavelength, and soon they are eloquently addressing subjects as vast as John Dewey, reading and “misreading,” the works of Ishmael Reed and John Ashbery, “The Waste Land,” how people give up on difficult books too easily, Voodoo, the racial politics of Huckleberry Finn, and Grindr. The microphone stays off.

After ushering the bystanders into an adjacent studio, Silverblatt asks Keene to spend several minutes recording himself reading aloud a lengthy section of the book, the opening story “Mannahatta.” The host likes to get the sound of the author’s prose on the recording, so that the texture of the book itself isn’t overwhelmed by interpretation. On a more practical level, the section can serve as filler to be edited in later if the conversation doesn’t catch sparks.

Once they begin the on-the-record part of their conversation, Silverblatt cannot contain his wonder: “What was it that you were seeking? Because I found these stories fascinating and as unlike the stories that I think of when I think of stories as possible. I was thrilled to be finding something genuinely new.”

Keene takes his host’s enthusiasm in stride. “I wanted to go against the grain,” he says, “even at the level of sentences, of paragraphs, and of form — to, from the bottom up, tell stories in which the language was … true to the story itself, as opposed to imposing, as the author, what I thought the language should look and sound like.”

After picking at the historical and cultural threads that lendCounternarratives its power, Silverblatt continues to register his pleasure at discovering such an unusually rich book. “These are really crazy stories. I don’t mean mentally ill. I mean stories in which what we expect cannot be laid out in advance, that as we read we’re being opened up to a whole new set of possibilities in fiction, yes? Does that argue that you’re impatient with what’s been happening in the texts that these texts are answering to?”

“To a certain degree, yes,” Keene answers.

By the end of this episode of Bookworm, Silverblatt takes inspiration from Counternarratives to reinvestigate the country’s founding myths: “The idea seems to be that if America would open up to the secrets brought to it from other cultures, we never would have ended up with the constricted, Puritan, closed-minded, frightened thing that Europeans criticize us for, because we are children who cannot accept the fullness of sexual nature — the fullness of nature itself. We cut down our trees!” At this point, the host remembers to ask a question. “So … how did you figure out that this was what you wanted to do?”

To the show’s producer Alan Howard, sitting in the room next door, it becomes obvious that this episode is dynamic enough to render the “Mannahatta” excerpt unnecessary. He communicates with the host via a shared Google Doc, typing messages in large font, all caps. “THIS IS FANTASTIC,” he writes.

Sending him out into the daylight, Silverblatt tells Keene that he will be reading whatever the author does next — whether fiction, poetry, or translation — but assures him that he’ll receive just as much pleasure rereading and appreciating the “crazy stories” under discussion, the ones whose remaining secrets he, after months of preparation and an episode’s worth of conversation, still seems eager to unlock.

Listen to Michael Silverblatt interview author John Keene on KCRW-FM’s Bookworm: