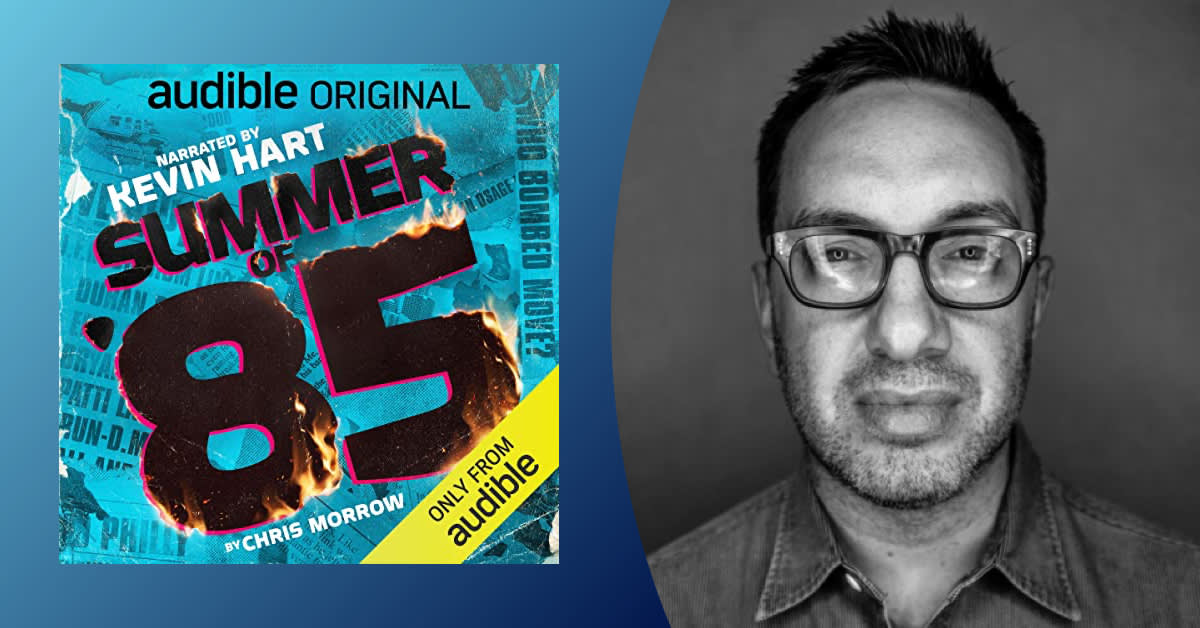

Along with co-creators Kevin Hart, Charlamagne Tha God, and SBH Productions, Chris Morrow gave a personal history of the summer that rocked Philadelphia. Here, Morrow takes us behind the origins of his Audible Original, Summer of '85.

The MOVE bombing and the Live Aid concert were two stories I’d wanted to tell for a long time.

I just didn’t know I wanted to tell them together.

Even though they took place in my hometown of Philadelphia exactly two months apart in 1985, they always occupied separate parts of my mind.

The MOVE bombing represented Philly at its absolute nadir. Since the organization was founded by John Africa in the early 1970s, it had been locked in a struggle with city officials. In some parts of the city MOVE members were seen as righteous revolutionaries. In others, they were seen as misguided and misunderstood activists. In my neighborhood, they were viewed as degenerates and outlaws.

But no one, no matter their opinion, expected what happened on May 13, 1985. The bomb dropped on MOVE’s home killed 11 members of the group, including five children, and the ensuing inferno would burn down 51 homes until a reluctant fire department finally put it out.

I remember watching the bombing on TV. As a teenager, it struck me as a total failure on the part of the leaders of the city. It was as if the racial tensions that were never far from the surface in Philly had finally broken through for all the city to see. A reminder that despite its name, meaning “The City of Brotherly Love” in Greek, Philly would always be a dangerous and violent town.

Live Aid, which took place at Philly’s JFK Stadium on July 13, 1985, seemed to represent Philly at its absolute apex. As much as Philadelphians hate to admit it, we have a complex about being a second-class city. Our sports teams never seem to win championships. People don’t dream about making it to Philly the way they do with New York and Los Angeles. We feel like perpetual underdogs.

Live Aid seemed to change all that. The biggest concert the world had ever seen was coming to Philly. Not New York, LA, or Chicago, but Philly! Led Zeppelin, Mick Jagger, Bob Dylan, Tina Turner, Phil Collins, Judas Priest, Madonna, Patti LaBelle, Run DMC, and scores more were going to take the stage while almost 2 billion people around the globe watched on TV. It was unreal. With Live Aid, we were finally winners!

It was for a great cause too, eventually raising $127 million in famine relief for African nations. Just two months after MOVE, it felt like maybe Philly was the City of Brotherly Love after all.

I’d never been to a concert before, but one of my friends scored tickets and I somehow talked my parents into letting me go. It was unbearably hot that day, pushing 100 degrees, and most of my buddies bailed after a couple hours. I was determined to make it to the Led Zeppelin reunion that would close the show, but by 7 PM I was back on my parents’ couch, watching the concert on TV with the rest of the world.

In the ensuing years, Live Aid would earn iconic status, but not because it raised millions for famine victims. Instead, people largely spoke about two performances that took place at the London version of the concert: U2’s act, which helped propel them from up-and-comers to rock superstars, and Queen’s ascendant set, which would become many fans' most lasting memory of the late Freddie Mercury. The Philly half of the concert, despite helping introduce the world to hip-hop via Run DMC, was largely forgotten.

It would not be the only event from Philly that summer that faded from view.

Despite the death and destruction it created, the MOVE bombing never seemed to become a major story outside of Philadelphia. In the years, and even decades, that passed, I’d always be shocked by how few people seemed to know about it. Even in New York, where I now live, whenever I bring up the story, I inevitably get the same reply. “The city really dropped a bomb on its own citizens? And killed innocent children? I can’t believe I didn’t know about that.”

In the early 2000s I partnered with a documentary filmmaker to potentially make a film about MOVE and the bombing. We put together a trailer and submitted it to a competition that was funding new films. I was sure we’d get backed. We didn’t.

I’ll admit to becoming a bit disillusioned. Maybe the world didn’t want to hear about a story that ends in the death of children and the destruction of a once thriving African-American neighborhood.

Then, a few years ago, I was scrolling through hit songs from the ’80s on YouTube (which I find myself doing more than I care to admit) when I came upon Run DMC performing “King of Rock” at Live Aid. Next to the stage was a massive logo for the concert: an electric guitar with the continent of Africa as its body. When I was at the concert, I’d barely noticed it despite its size. But it made me think.

All these rock stars had been in Philly to support “Africa” (never mind that the famine was only in Ethiopia). But no one spoke about the fact that just two months earlier the city had bombed the group led by John Africa (every member of MOVE had adopted the last name Africa too).

Philly had shown its generosity and compassion in helping “Africa” the very same summer it revealed its brutality in dealing with the Africas.

That, I realized, was the story I wanted to tell.

It’s been a challenging task. One of the first things I realized about this story, especially when it comes to MOVE, is that people have distinctly different views about what happened.

To many Philadelphians, especially African Americans, the MOVE bombing is the ultimate result of a racist power structure run amok.

To others, especially working-class whites, MOVE was a symbol of a city spiraling into lawlessness and anarchy.

It’s a divide that is as wide in Philly (and around the country) today as it was 35 years ago.

It can be disheartening to think an event as impactful as the MOVE bombing didn’t result in any meaningful change. That issues like police brutality, racism and urban violence are just as bad, if not worse, than they were back in the summer of ’85.

Just like it’s heartbreaking to learn that Ethiopia today is plagued by a terrible famine in the very same region that inspired the Live Aid concert.

Maybe that’s why those stories haven’t been properly explored. Some parts of the past seem too painful to revisit. We’d rather leave them in the shadows of history.

But if you don’t learn from history, you’re doomed to repeat it. And we’re not talking about ancient history either. These events happened in my lifetime. Many of the victims, as well as some of the perpetrators, are still alive. The wounds from the summer of 1985 are still fresh.

The idea of learning from history, instead of running from it, is what inspired me to create this series. And what excited Kevin Hart and Charlamagne Tha God about producing it. I believe it’s also why Kevin wanted to lend his voice to this project. He’s said that Philly is where he learned some of the hardest and most important lessons in his life. Even though he might not reside there anymore, he lives, eats, and breathes the city’s energy every day.

The hope for this series is that it can shine a light on the sequence of miscommunications and clashes of egos and systematic racism that led to the ’85 bombings, so that if similar scenarios arise in Philly, or anywhere around the country, we’ll be better equipped to address them early—to put out the sparks before they turn into the kind of inferno that lit up the Philly skyline in the summer of ’85.