Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

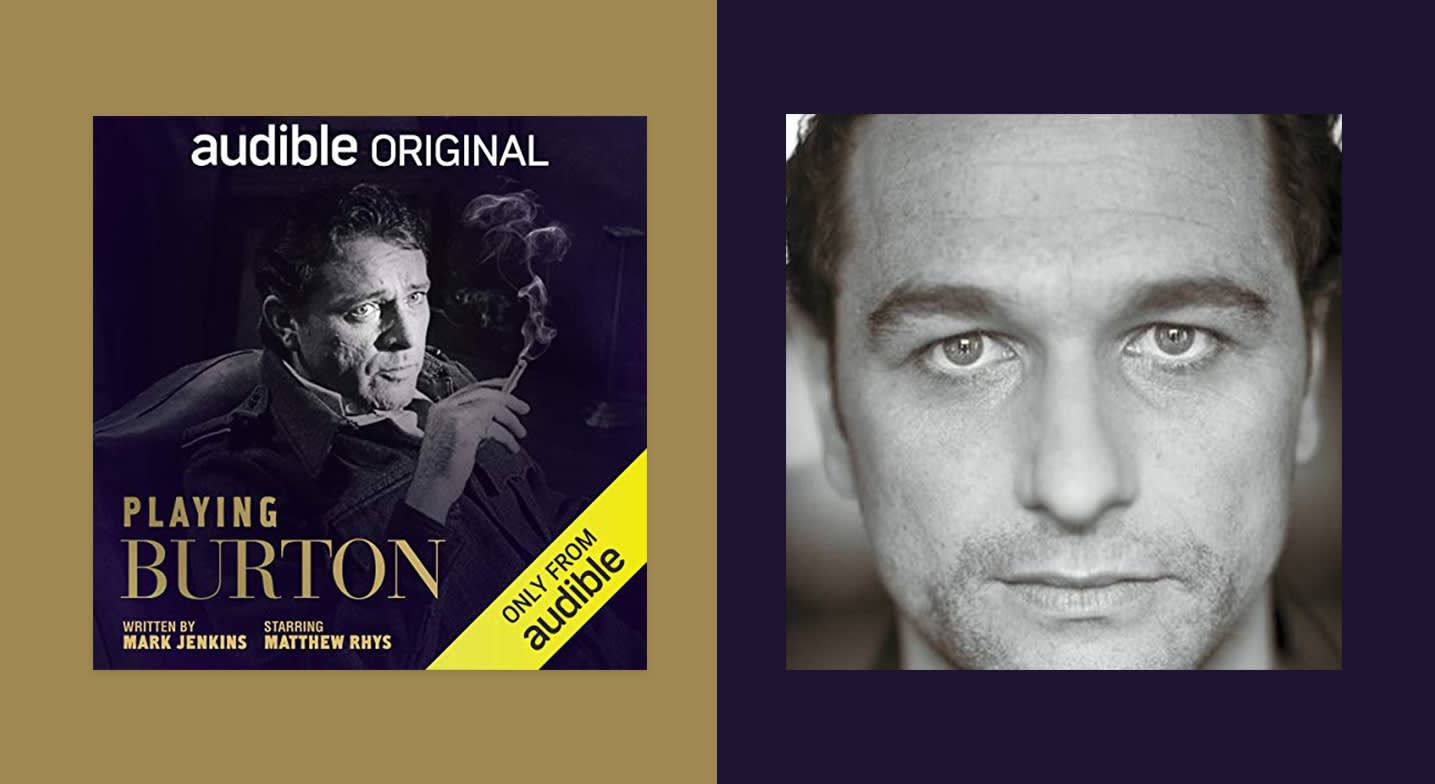

Emily Cox: Hi. I'm Emily, one of the editors here at Audible, and today I'm so excited to be speaking with Emmy Award-winning actor Matthew Rhys. You may know him from his role in The Americans or the amazing Perry Mason reboot, which is now on HBO, or one of my favorites, Death Comes to Pemberley. But I assure you, you will also want to know him for Playing Burton, his new project with Audible Theater. Hi, Matthew. Welcome.

Matthew Rhys: Thank you very much. Very happy to be here.

EC: Thank you so much for joining. I love this play. I've listened to it probably about two and a half times. I've sort of bookmarked a few places. There's a lot in here. It really made me want to dust off my English major hat and I've been Wikipedia-ing a lot. I know a lot more about Richard Burton than I ever thought I would, but it's beautiful and it's complicated, so I'm really excited to be talking to you about it. It was originally written in, I think, the mid-'90s and you saw it when you were a student in London?

MR: Yes, I was. In fact, it must have been '97 I saw the production. I think it was at the Hammersmith Studios then, and I was at that time already an enormous Burton fan. I don't say that lightly. He really was the reason I went into this, so I just remember one of those moments. I was in college. I was up at the Royal Academy and I saw this little poster saying Playing Burton. I was like, "What's that?," and then went to London and was really taken aback by this piece because it was such an interesting take on his life.

"There's a line in the play where he says... "I did it all in a language that wasn't even mine." And there was a lot [in that] that I resonated with Burton."

EC: In the audio version there are some extra sound effects added in. Was that what the experience was watching it? I mean, it's a one-man show but—

MR: No. It was as a stage play. He was doing all the actions onstage himself, live, so there were no real sound effects. I just remember at the beginning, it starts with his obituary on the 9 o'clock news for the BBC. I remember having this striking moment where you hear his obituary and then he begins to look back on his life. So that was the only true audio in the piece. But I remember it was such a great tool to have him present and then reflect back.

EC: And say, "No, no, that's not how it went down." Can you tell the story of how this came to be at Audible? You brought this to Audible, right?

MR: I did. I remember starting to go see the one-man plays in New York. I was like, "Oh, I would love to play Burton." And then COVID hit, and then the theaters closed, and my agent said, "Well, look, what about doing it as a piece for Audible?" The transition is usually done in the live theater or a lot of those one-man or one-woman shows and then becomes an Audible piece or can become an Audible piece.

And he goes, "Why don't we leapfrog the theater part and see if they're interested?" I did, and I was incredibly happy that you were, because it also was another version. I've seen the stage version and my friend Wyndham Price had directed the film, for which he won a Welsh BAFTA. And then I was like, “Oh, this is an audio piece. This is beautifully and easily, seamlessly an audio piece.” Especially for a man who was known for his voice.

EC: Yeah, I was thinking about that. Obviously he had a huge career. He would have been an amazing narrator. I mean, we would have tried to hire him for everything.

MR: I would have too. There's a funny story when he was doing Where Eagles Dare with Clint Eastwood, and Clint Eastwood kept saying, "Oh, give that line to Richard. Give that line to Richard." And then the director finally went, "Why?" And Clint Eastwood went, "Because he's the one with the voice," which is very fair of him to say that because Eastwood has his own voice. But that was one of the things I grew up on as a young boy in my bedroom listening to Richard Burton. Not the films. It was the poetry readings and the narration of a lot of Dylan Thomas's work, because they were great friends.

EC: And [Dylan Thomas] was Welsh?

MR: Yes, he was. And the Hamlet that [Burton] did on Broadway, those are all audio that I listened to, to this mesmeric voice.

EC: You said earlier you really wanted to act because of Richard Burton. How was he seen when you were growing up in Wales? Is he a hometown hero there? Because he has a complicated legacy.

MR: Incredibly so. You know, his ascent was…kind of meteoric. He hit the zenith of what Hollywood was. He was the true star in that respect. I have to be careful with my words about the poverty he came from, but he came from a mining family that didn't have much money, and lost his mother early and—

EC: A huge family, right?

MR: Huge. 12 siblings. And then [he] changed his name and took this path. There was a book, a biography of him called Rich, by a famous author in Britain called Melvyn Bragg, and I remember reading that when I was 16. And he, to me, was the pioneer in Wales, still was. He was the first that went, that left and claimed and conquered Hollywood. And then Anthony Hopkins, who was from almost the next street—they're both from Port Talbot—did the same. So, Burton was the first, the original pioneer. There's a line in the play where he says, "I did it," because his first language was Welsh, and he goes, "I did it all in a language that wasn't even mine." And there was a lot [in that] that I resonated with Burton. He just made it seem it was possible because his journey had been so great and arduous at times, and so, so much of a roller coaster.

EC: Right. It's amazing that you mention that line. I've bookmarked that and I wanted to ask you, specifically, about that, because it's really fascinating and it resonated for me. Welsh is your first language, right?

MR: Yes.

EC: I was thinking about how this connects a little bit to your role in The Americans. This idea of living a life in a language that's not your own. Do you think you're drawn to those kind of stories in some way because you're—

MR: Yes. I absolutely suppose, subconsciously, I am. This'll sound terrible, as if I'm blowing my own horn, but when I won the Emmy—"When I won the Emmy"—I did all the press afterwards, and I remember immediately after this, the press going, "Oh my god, this incredible part." And I remember thinking I was almost choked with impostor syndrome because ultimately what I was doing was playing an alien who's pretending to be someone else. And then I pretended to be other people. I was screaming in my mind, "That's all I've ever done my whole life! It's not a sketch! It's what I do!" It was an odd moment. But yes, I'm drawn to those things.

And I was incredibly drawn to this piece because what it does, it explores... Burton had a complicated relationship with his father and then was taken under the wing of Philip Burton, this man who inspired him and kind of nurtured him.… From a very early age, I think he was 16, he took Burton's name. I was like, where does this journey begin of Richard Jenkins, which was his real name, becomes Richard Burton? Or is it a matter of stages, where at each stage he evolves as Richard Burton. What is that? Are you taking on a persona or are you just evolving as you would anyway? Which I hardly think is most of the truth.

EC: Right. And obviously this play is fiction to some degree, right? Because the playwright had to sort of imagine it. But if we were to take this as his biography, it seems like it was a calling. He talks about his shadow taking off and he had to follow it or lose himself. He didn't have a choice in it.

MR: I love that.

EC: It's kind of interesting.

MR: That's one of my favorite pieces of that play. The language is so poetic in that moment he talks about the boy who has the shadow that takes off across the Atlantic and he had no choice but to follow. Yes, it's very true that he had this.... That's the other element in the play that's questioned a lot, because in his life it was his destiny. There was this old vanguard of British theater that bemoaned the fact that he went to Hollywood and did what he did. I firmly disagree with it. I think he bestrode both empires perfectly well. He came to Broadway and conquered with an incredible Hamlet, and his film work is incredible. There are so many film forms of his I love. But he was, I think, there was an element of him that was caught by that. They kind of said, "He relinquished the throne. He was the next prince." And he fought that to a degree. I think it ate at something in him to a degree, a small degree.

EC: Right. But there seems to be a criticism or an agreed-upon critique that he didn't live up to his potential. But I don't know. What do you make of that?

MR: It's part of the play that I was interested in because it explores whether there was this turmoil in him. Because there are times he was vitriolic about the opinion that people have of him during that. And I wonder if he was so assured of himself and what he did he wouldn't be that angry about it. But he was. He did do an incredible amount of stage work. He was an incredible Prince Hal, you know, thundering reviews in the Royal Shakespeare Company, and then went to Hollywood. Many bemoaned the fact that he did. But that, as I say, was one element of the play that I was interested in: how much of it ate away at him, or not? I think it's there to be judged somewhat.

EC: Yeah. My first encounter with Richard Burton was actually in a novel that I read a few years ago called Beautiful Ruins. Do you know that one?

MR: I do. I haven't read it, but I know they've been trying to make a film for a while.

EC: Oh, I didn't know they were doing that.

MR: Yes, and it's kind of come and gone a couple of times. It looked like it was going [to] go twice with some big directors attached. I was always poking at my agent going, "Who's playing Richard Burton?"

EC: I was going to say that sounds perfect. That would be amazing. That was a really great one. So, I wanted to ask a bit more about how this, the performing, was for you. It sounds like you may be reprising this role at the Minetta Lane Theatre at some point once COVID is behind us?

"[Audio] lasers the importance of each word, because then nothing can really go to waste. There's no use of any facial expression that would aid you."

MR: I would love to. I would absolutely love to. [Performing] was a bigger challenge than I thought, because when I read it under the thought of, "Oh, could we take this onto an audio piece?," I read it, and I went, "Oh, yes! This would work. This would work perfectly." Then I went, "Oh, I don't have my face and my body to help me." You realize the pressure that is literally all on the audio. That's what Wyndham, the director, and I worked through: Where does the storytelling need to be punctuated? Or the volume raised? And I don't mean in the literal terms. Purely through the language and the words, and it kind of magnifies, lasers, your concentration, certainly. And [audio] lasers the importance of each word, because then nothing can really go to waste. There's no use of any facial expression that would aid you. It's all in the spoken word, and the fact that it was Burton, who was the kind of king of the spoken word, I always in the back of my mind going, "Oh, God, how would he do this?"

EC: Yeah. Am I living up? But I thought it was funny that you took your jacket off. You're like, "Oh, this might rustle." I wonder if that's something you learned through this process when you were in a sound studio.

MR: Well, yeah, yes, I was. Funnily enough, there was a term we did at the Royal Academy of [Dramatic Art]. I do remember a few things like: "Day one, don't wear any clothing that makes a noise. Pull your pages taut when turning a book," or that kind of thing. I do remember that one. But that was a very long time ago.

EC: What I thought was really intriguing about your performance, and that's really successful, is that I could hear when you were young Richard and when you were being old man, grumpy, drunk Richard. How did you approach sort of, modulating yourself to—

MR: Oh, that was a big one. It's a big one I thought about a lot. You're very scared or aware that you could fall into cliché with that, because you are trying, in some ways, to differentiate in very clear ways. I kind of left that up to Wyndham, and he was like, "You know, well, maybe it's bit too, too old man. Or it's a bit too, too young boy." He was the guide on that. Like I was saying about this Audible experience, those elements become far, far greater in your armory. All those elements become magnified.

EC: Right. It becomes just that much more important.

MR: Yes. Or, as if to aid and help.

EC: Right. So what are you working on now? This weird season that we're in.

MR: No word of a lie, I'm scouring things. I'm scouring things I can bring to Audible, because I haven't worked in a year. So, nothing at the moment. I did a season of, as you mentioned earlier, Perry Mason—oh, wait, I can't even remember what year that was. It was a year ago today we finished. Or not today, last week. So we've been waiting to see when we're allowed to shoot the next season, because it would be in California. Because of COVID, that's proving a little tricky. So it probably won't be for another six months. So who knows what I'll be doing.

EC: Matthew, thank you so, so much for joining. It was a real pleasure speaking with you. And for everyone listening, you can find Playing Burton on audible.com today.

MR: Thank you.