Seven years ago in Monterey Bay, California, wildlife filmmaker Tom Mustill had an unshakable encounter with one of nature’s most awesome gentle giants. An adult humpback whale, larger than a bus and weighing several tons, had breached on top of Mustill’s kayak, capsizing it.

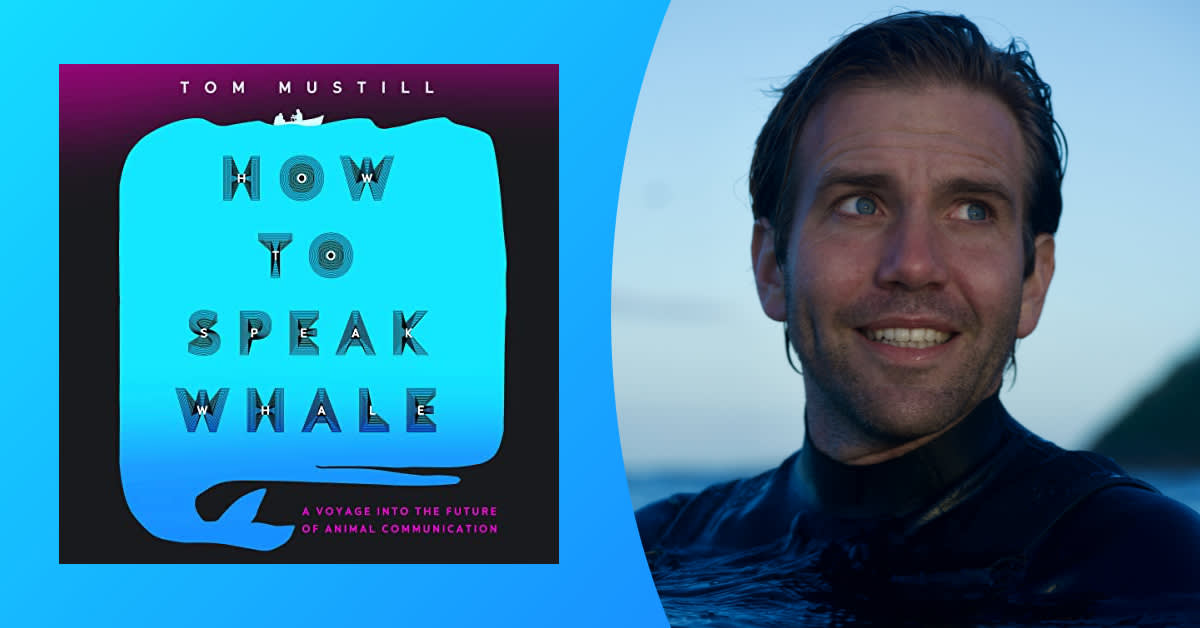

A video of the astonishing incident subsequently went viral, and Mustill, who survived entirely unscathed, found himself driven to better understand these creatures, how they think and feel, and how to establish a sense of communication between animals and human beings. In How to Speak Whale, he chronicles the tech advancements promising a method of decoding animal songs, calls, bellows, and roars, offering a window in their complex emotional lives and the undeniable intelligence of beings other than ourselves.

Audible: In 2015, you survived a brush with a humpback whale who breached dangerously close to your kayak. How did this close encounter alter your perspective on ocean life and lead you to further probe the relationships and likenesses between human beings and the creatures we share our planet with?

Tom Mustill: It had already been a year for thinking deeply. My father, Michael, who I was very close to, had passed away in April and life had that recent-grief quality of being very stripped back. Everything was fragile, and time was scarce. I wanted to experience what I could fully, avoiding the distractions and mundanities that one can allow to build up and get in the way. In the words of John Cheever, who [my] dad had admired, I wanted to "stand up straight, admire the world."

Then the whale leapt onto us. It actually hit our kayak, smashing the front of it in. We were improbably lucky to survive unharmed. I already had a healthy respect for ocean life; it is not the job of whales to avoid holidaying humans! But this experience and the fact that it went viral linked me to whales, whether I liked it or not. It meant people told me their stories about whales, and sent me links to things, and this built on my existing fascination. I had never thought much about how similar or different they were—that came later, when I learned more about what recent discoveries had revealed about their lives. In a way, the spectacular and, for me, almost beautiful encounter drew attention to something that had always been in front of me. And in my stripped-back grief mode, I followed this, not knowing where it would lead.

You’re perhaps best known as a documentarian who has worked with the likes of environmentalist Greta Thunberg and the great Sir David Attenborough. What was it like to shift media and write a full-length audiobook? Did your knack for visual storytelling lend anything special to the writing process?

In most of the films I've worked on, whatever the imagery or scenes you have captured, you need to help people understand what they are witnessing, to put yourselves in their shoes and ask, "Why do I care about this? What does it mean to me?" For this, the script is key— working on it to strip away things that might confuse, shuffling things around until they make sense to someone outside of your head—especially in films where you have to explain complex science to audiences who might be coming to it for the first time.

I've been fortunate to work with some of the best communicators out there, including David and Greta, and have learned a lot from them and the filmmakers I apprenticed under. I always try to focus on the connection between the animal and human worlds and those of the viewers—to invite the audience into the lives of the people who've invited me in and try to get across the privilege that I've experienced. Though I didn't do this consciously, I think I probably approached the audiobook in a similar way, like a magpie collecting little bits of the lives of the whales and the humans in the story, hoping to assemble a scene with spoken words rather than with images.

I also brought with me a healthy respect for my editor! I think a lot of writers find it hard to have an editor cut lots of what they've poured themselves into, but in filmmaking, this happens every day of the edit. I've learned over 15 years to find another set of eyes invaluable, almost looking forward to the bracing and painful opinions about killing your darlings in the same way I used to anticipating a freezing cold swim, with that strange mix of fear and glee. So, perhaps this helped me be less precious when my editors Shoaib and Colin got involved in the audiobook!

The biggest shift was the most positive. People cared what I personally had to say. In documentaries, especially wildlife, directors and their authorship are no longer valued. Can you name a wildlife film director? It's unlikely. This hadn't been the case when I had begun my career, and I feel the films have all become more boring and generic because of this. You rarely get the feeling that you're in the hands of one storyteller and their particular vision, and this is what I love in cinema and had come to miss in my own work—the chance to express what I had felt and seen. So, it was a surprise to put down this audiobook and find people liked what I had to say. It was quite emotional, to be honest, as I think I'd squashed the bit of me that felt anyone might care. Finally, I tried to bring a bit of extra atmosphere-building to the audiobook, to take the opportunity audio presents for a richer experience. We have included lots of sounds gathered in my research and folded them in. It is a story about sounds, so in a way, an audiobook is the perfect medium to experience it.

There’s a shattering musing in your book that conveys the stark reality of climate change and ecological destruction: “To be alive and explore nature now is to read by the light of a library as it burns. Could our discoveries prompt us to put out the flames?” Personally, do you foresee further exploration of animal communication methods and emotional intelligence contributing to the greater conservation effort? In what way does this research have the potential to shift thinking about wildlife?

I really don't know, and I can't imagine anyone being in the position to know the answer to this—we all see such small slivers of what is going on. And so often, we have miscalculated both our capacity for change and what brings that change about. I do know that we can learn from the past, and looking into the past with the life experience I've had, it does seem that whenever humans have changed from the norms of powerful people doing unpleasant things to less powerful ones (the story of our relationship to nature at the moment), it has taken an alchemy. You need alternative ways of doing things that they can shift to, you need an awareness of the problem. But most powerfully and hard to bring about, you need an empathy and groundswell of public feeling about the injustice that fires this all up. Then, suddenly, a change in the existing unfair relationship can feel inescapable.

This is why the story of how the whales were saved before, helped by Roger Payne discovering and popularizing that they had song, is so instructive and occupies a central position in this story. All I do is try to contribute to this empathy and fellow feeling for the natural world—that is what I do in my film work and in this audiobook, and it is all in the hope that I can contribute. At least I have tried, but I do not know if it will help. I hope so.

In How to Speak Whale, you investigate the potential in recognizing patterns within animal communication using AI technology, research that has the potential to allow us to better understand non-humans and forge stronger interspecies bonds and connections. Other than whales, are there any animals that you’d be most interested in comprehending? Why?

I would love to speak to dogs and cats. They are around us all the time, they have evolved with us, they know us intimately. Selfishly, as a human, I want a mirror held up to us, in the way that your own family knows you so well that they can always put their finger right on what's bothering you and what you need. I think it could be pretty awkward and funny also. People often buy companion animals for unconditional love. But what if that love turns out to be conditional? What if your dog despises you, prefers your hated neighbor, or, perhaps worse, is indifferent? Can you imagine the fallout? Would you still pick up their poop if as you looked into their eyes you saw someone who didn't really like you that much? I think that is unlikely for most dog owners, but it is a devilishly intriguing thought.

I would also like to speak to a Neanderthal or other hominid (members of our homo family, all extinct now sadly), as they were so similar in many ways, but different. How did they see the world? How did they see us? What did they think of the great questions of love, fate, existence, beauty?

For listeners of your book, are there any other audiobooks or podcasts you’d recommend to folks looking to learn more about animal behavior and communication, Earth and its myriad ecosystems, or the intersection of technology and nature?

These are huge topics and there is so much to find—it is a golden age for audiobooks exploring these themes! I love the podcast Radiolab—the production is so delightful, and they manage to avoid the pitfall of finding themselves more interesting than their subject matters that so many podcasters, in my humble opinion, fall into.

Audiobooks I have loved recently include Merlin Sheldrake’s Entangled Life, which changes how you look at other ways of living and even looking at nature. Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer also expertly shifts perspectives. The Overstory, the fiction by Richard Powers, changed how I thought about trees. Carl Safina's Beyond Words: What Animals Think and Feel is a masterclass. And anything by Ed Yong.

The audiobook that has stuck with me the most is Four Thousand Weeks by Oliver Burkeman. It made me reconsider my relationship to time and technology, and I've listened to it three times now! I always come back to Rachel Carson and would love to listen to her The Sea Around Us.

Probably the most surprising bit of storytelling, the one that has stuck with me the most, is Jaws, the original novel by [Peter] Benchley. In it, there is a description of a mother fur seal as she races, unsuccessfully, to escape the shark. It is so vivid—terrifying—that it puts you so into the experience. That has never left me.