Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

Part 1

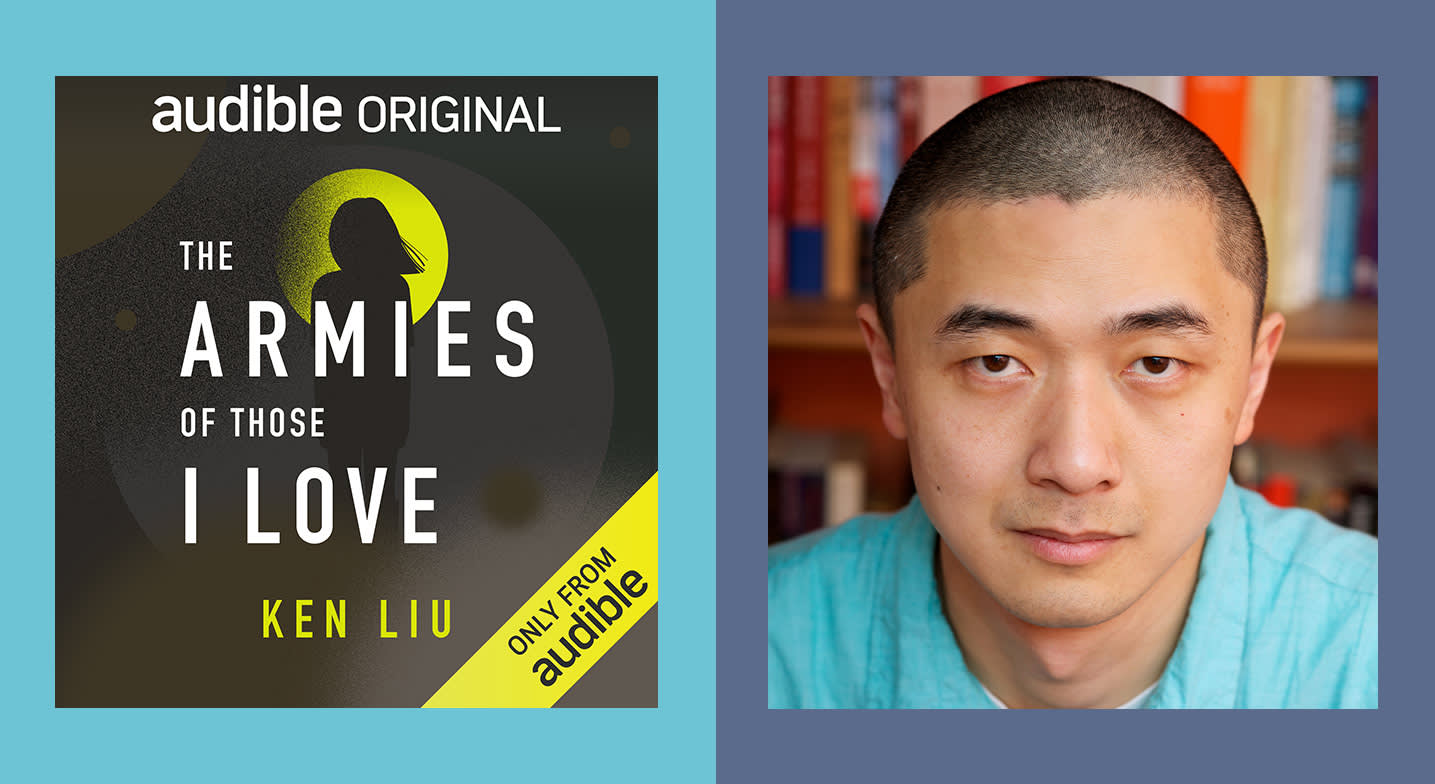

Sam Danis: Hi, I am Sam, Audible's sci-fi and fantasy editor, and I am super thrilled today to be talking with writer Ken Liu. He is the Hugo and Nebula award-winning writer of several short story collections, including recently The Hidden Girl and Other Stories, and The Paper Menagerie and Other Stories [2016]. He's also the author of an epic silkpunk fantasy series, The Dandelion Dynasty, and the translator of several works of Chinese sci-fi, including Cixin Liu's award-winning The Three Body Problem. Today, we're here to talk about all of that great stuff, plus his brand-new Audible Original story, The Armies of Those I Love. Welcome, Ken, and thanks so much for taking the time to chat with me today.

Ken Liu: Thank you so much for having me, Sam.

SD: Very excited to dive into this story. I got the chance to listen to it a little while ago. To set us up, I'm curious to just hear a little bit more about this story in your own words and how it came to be.

KL: Sure. I can go in great depth about the story. It, in some ways, is my favorite story I've written the last year. But briefly, The Armies of Those I Love is my meditation on Walt Whitman and the city of Boston, and it is a post-post-apocalyptic world in which the great cities of the world have become these roaming machines. They're giant walking stone islands migrating over the continent, a continent where climate change and other disasters have depopulated Earth. The only survivors now live on these roaming cities. It's a story of a young girl who tries to survive in one of these cities that used to be Boston and how she ends up discovering how the world she lives in came to be and what she can do to try to fulfill her hopes for all the people she loves.

SD: It's such an interesting story. And correct me if I'm wrong, but you're in Boston. You live in the Boston area, is that correct?

KL: That's right. I've been here since college, so more than 20 years now. It's home, and so a lot of my stories are always set in and around Boston, and this is one of them.

SD: That's great. I went to Boston for school as well. It's one of my favorite cities. I'd live there in a heartbeat again, if I could. You say this is one of your favorite stories you've ever written. We're always very excited to hear that. What inspired this story for you? It's such a unique concept of this post-post-apocalyptic world, as you say, where cities can actually move.

KL: There are many sources of inspiration, but the most direct one is probably just reading over Walt Whitman's I Sing the Body Electric, which is a collection that I love. I just read him all the time, and suddenly I thought about how Whitman's poetry ties into my own aesthetic about storytelling and the importance of storytelling. So just to set you up a little bit, one of my great theses about storytelling is the idea that, as human beings, we are actually defined more by stories and by understanding the world through stories than logic or reason or rationality. We often talk about rationality and reason as the most important qualities of being human, but I actually don't think that's true at all. I think stories are far more important.

As human beings, we are actually defined more by stories and by understanding the world through stories than logic or reason or rationality.

I'll go a little deeper into this. I'll ask you and the listeners to think about a word or some sort of quality, some positive, important concept that's very important to them—faith, love, what have you—and just think about that for a few seconds. And what I think will happen is... I'll use myself as an example. The word I was thinking of is love. And what comes to mind isn't the dictionary definition, it isn't any kind of philosophy, it's not any kind of abstract reasoned definition of what love is. It's just an image, a memory. It's a memory of my grandmother sitting by a faint lamp. This is when I was a small child and she was trying to knit a sweater, and I could see that her hands were very gnarled and cracked from the cold, the dry winter weather. She had arthritis, so it was very hard for her to move the needles. And I could see that she was in pain, so I asked her, "Grandmother, are you in pain?" And she says, "Yes." And I said, "So why don't you stop?" And she was like, "Well, I don't want you to be cold." She was making the sweater for me, and that's what I think about all the time. For anything that matters to you—courage faith, hope, what have you—when you think about these important words to you, what comes to you isn't going to be some abstract philosophy or some dictionary definition. It's going to be a story. It's going to be a memory.

I think that's the way we understand these words. We human beings come to understand the world, not through abstractions but through very concrete stories and experiences and these tales that form a personal mythology for us through which we understand the world. So the way you understand the word love isn't going to be the same way I understand love because we had different experiences. We have different stories that define these words.

As we grow up, as we end up understanding the world more, we collect more stories. And eventually, at some point, our own personal journeys take us to these places where we are no longer merely the recipients of stories. We begin to become heroes and demigods in other people's stories, you know, our children's stories or our friends' stories and those who we mentor and teach and lead.

That's how the generations go on. We pass on these stories from generation to generation. We love others as we were loved. We are courageous for others as they were courageous for us. To me, that's how culture is built. It's not really about abstract, high, lofty declarations. It's really about, very simply, enacting and making ideals that you think are important, true, in the same way they were demonstrated to be true to you. You end up becoming the stories that were important to you, and that is how you keep the pact between generations.

Anyway, all that aside, The Armies of Those I Love and Walt Whitman seems to me very much about that. Whitman’s poetry talks about generations, about this epic poets’ view of life, of how you go on and each individual contains multitudes, and the pact between generations goes on and then the mythology of a nation is built up of the mythologies of individuals passing down these stories from generation to generation. I wanted to write a story that made that true.

The hero of my story, Franny Fenway, is a girl like that. You begin to understand the world through her perspective, and it's a set of stories. She has these memories of her grandmother, who is no longer with her, and she misses her grandmother very much. The whole story is about her attempt to live up to the way she was loved by her grandmother and the way that she wants to become the hero for those who will come after her in the same way that her grandmother was a hero to her.

The mythology of a nation is built up of the mythologies of individuals passing down these stories from generation to generation. I wanted to write a story that made that true.

She takes on this wonderful journey to discover the truth about her world and to take a stance against something that she feels is deeply unjust. She takes great personal risk, and it's not because she was inspired by some abstract philosophy. She was inspired really just by the fact that she wanted to live up to the story that she had been inspired by. She wanted to love others as she had been loved, which is, I think, probably the most truthful philosophy of life that I can think of.

SD: That's a really beautiful way of describing it too. And thank you for sharing that story about your grandmother. On a personal level, I knit as well and as soon as you started describing that, I started thinking of all the things I've made for others and how much love and attention went into that. And everything really does end up as sort of its own story. It's a very relatable kind of experience.

Going a little bit into storytelling too with this story, written words are rare in this world, and stories are passed down through words and just through oral tales. The way this feels so fit for the audio format, just because of that, is this a story where the story came first and then it kind of fit into the audio, or when you knew you were going to write a story for audio, did this story instantly come to mind? Tell me a little bit about that process.

KL: I really enjoy exploring and trying to craft stories for specific mediums in which they're being told. I recently wrote a story for an interactive fiction magazine. I had to figure out how to do that because, when you're thinking about writing interactive fiction, it's very different from the typical literary fiction. And I also have to think a lot about how you craft a story differently for reading online on a tablet or an e-reader versus on the printed page, because they are, in fact, very different.

A lot of authors discover this once their books are out in print. I had to sort of figure this out as it started to happen, because the way you write for the webpage or the Kindle is very different from how you would write for a traditional printed page, and the way you would do it for a magazine is different from a book. And I had to sort of work through for myself what the differences are and how to craft your text to that medium.

Now, the audio format is very important, but I don't have a lot of experience writing specifically to audio. In fact, a lot of my stories are not really amenable to audio presentation. For example, one of the stories in my second collection, The Hidden Girl and Other Stories, has this story at the end which literally is made up of the same story repeated three times, each time with certain pieces of texts removed. So there are holes left on the page. That kind of visual presentation is very difficult for an audio performer to... How do you do that? A lot of my stories do have difficulties being translated into the audio format.

When I knew that I was going to do this piece for Audible, I set out from the start to try to write a story that would work better in audio format than any other format. This has to be audio first, and this has to be the primary way that people experience it. I did a lot of thinking and reading about differences in the way we process language visually versus through the ear, and there is just a lot of cognitive science behind it.

There are things… It's just fascinating how writing really changes the way we think about language. In fact, all of us being a product of a highly literate society, really, even the way we speak and evaluate speeches and processes, realistic dialogue, whatnot, all that is deeply influenced by the way we think about written language. So when I was trying to write the story, I had to sort of think about, "How do I get away from the habits I've acquired as a primarily visual writer or writer for the printed page? How do I actually write something that will be performed, and that can actually work well, then be processed linearly by somebody just listening to it?"

It was challenging, and I ended up having to go into poetry quite a bit because poetry is one of the oldest art forms that prizes the orality over literacy. I needed to really get into poetry again and think about how the rhythms work and try to craft my prose to fit the rhythms I wanted, and to adopt the patterns of oral storytelling in some sense, the way it sort of loops back on itself constantly, the way it constantly reminds the listener where we are, what's going on, the way you have to indicate as much as possible who is talking at any moment, all of that.

She wanted to love others as she had been loved, which is, I think, probably the most truthful philosophy of life that I can think of.

I did try to craft the story primarily and specifically for audio reception. Hopefully, listeners will enjoy it, because that was the intent.

SD: That's great. I love that you took such a nuanced approach to it, and I think it really shows when you do listen to it….

The narrator of this story is Auliʻi Cravalho, who is the voice of Moana [in Moana], which is just delightful. I think anyone who's seen that movie…will recognize her instantly. Have you had a chance to listen to it yet? And what did you think about her performance?

KL: I have actually not had a chance to listen to it, but I'm so looking forward to it. Auliʻi was my top choice when we were discussing possible narrators. Just the energy she brings to all her roles and the way she has such a strong personality—such a great match for the heroine of the story. I'm really looking forward to how it's going to come out. It seems like it's going to be a real treat for listeners. I'm super excited to hear it.

SD: Yeah, it is. She brings that youthful energy and yet that deep introspection that the character has. She does a really fantastic job with it. I really think that listeners are going to enjoy it, and probably want a lot more of her narration in the future.

I have listened to it, and one of the things that struck me when we talk about writing for audio is that so many of the mentions in this story are really meant to be heard. There's a real satisfaction in recognizing certain familiar phrases. So there's a city called Boss. I can guess what that is. There's a character named Santa Mon, Lax, L-A-X. It's really interesting. I'm assuming that was all purposeful because you seem very methodical about how you write for audio.

KL: That's right. That was one of the fun things to try to create a post-post-apocalyptic world. I was thinking about how we understand the ancient world and the way we imagine the times of Cleopatra, Caesar, and all the blanks we have to fill in and the way we think about what it's like. And so I wanted to craft this world and how they think about us. In this story, we're known as the otizens. We're the old people who destroyed the world, essentially. We're figures of myths and legend to them.

All the roaming cities are named after their airport codes, so you have Lax and Boss and so on, and many of the living machines that have taken over after the humans were destroyed take on names unique to their cities. Here in Boston many of the various guardians, the machines, are named after parts of Boston. And the districts of Boston have been changed and corrupted as it goes through oral storytelling. You as the listener will have to do some thinking to figure out what the originals probably were. That was all intentional to craft this world that has evolved, or devolved, from where we are.

But I think a lot of the fun stuff also is just to keep in some little local jokes. The fact that some of the characters have names that I think Bostonians would chuckle at because there's just a lot of very Boston things in there. Hopefully listeners will enjoy it.

SD: I certainly got a small thrill out of those small recognitions. I encourage listeners to imagine you're listening to something 100 years in the future and kind of get that sense of memory from those nice audio insertions there.

So this is a short story, and you're a short story writer, but you're also a novelist. You have a series of novels. What do you enjoy most about writing in the shorter format, and how is it different from spinning a whole story in the course of a longer novel?

KL: Well, I think probably the biggest difference between writing a massive epic fantasy versus a short story... I mean, it's really kind of funny. My career has just taken me to very strange places as a result of working in these very different formats. For a long time, I was writing short stories mainly because that was the only way that I could write at all. I had a very mentally demanding job, and I had very little time to write, and short stories were about the only thing I could do because I could keep the whole thing in my head and I didn't need to, you know, outline, I didn't need to track dozens of characters or anything like that. So I could work in the short format.

For a while, I was writing many, many stories, all of them under 1,000 words, and there's a unique joy to writing stories that short, because you can work with negative space a lot more. Oftentimes, the way you make various short stories work is to just sketch in a very few tiny little hints of the world, and then tell the reader to figure all the rest out for themselves. Because so much work is being done by the negative space. It's very pleasurable to try to figure out just the right details to put in there to evoke a much larger world behind it.

You can also cheat a little bit in a short format. You don't need to necessarily work out everything. You can just focus your attention on one very tiny corner of it and hope that the reader can do most of the work for you and figure out all the rest of it on their own. I really enjoy that part of short fiction. You can skip very quickly from world to world. You can do a lot of the experimentation in form, in structure, in voice, in point of view, in narrative technique. I feel like short fiction really gave me a lot of opportunities to just explore and experiment.

If something didn't work, it's no big deal. You didn't invest a huge amount of your life to it, so you can easily switch gears and try something else. I really loved that, which is why I ended up having over 150 short stories and whatnot published. On the other hand, writing massive epic fantasy, which at this point the series is over a million words, is a very different experience. You know, 1,000 words versus one million words is a huge difference. And it's not just a difference in terms of length. It's actually different in the way you have to structure the whole thing.

When I'm doing epic fantasy, I have much less recourse to negative space. I cannot expect the reader to do nearly as much work as I can in a short story.

I sometimes use the comparison of, a short story is like an insect, whereas a massive epic fantasy novel is more like an elephant. And it's not just that there's a difference in size. There's actually a difference in structure fundamentally because you can't just take a mosquito and scale it up to the size of an elephant and expect that creature to survive. Biologically you can’t, because insects don't have an active respiration system and the ratio between surface area and mass is such that a creature like that would collapse and also suffocate. They just won't survive.

When you're doing a novel versus a short story, you also have to account for very different things. The way narrative energy is derived, the way you hold the reader's attention, the way you satisfy the reader's curiosity of the world, all of that is very different. I find, when I'm doing epic fantasy, I have much less recourse to negative space. I cannot expect the reader to do nearly as much work as I can in a short story. I have to do a lot more of the work myself and fill things in.

I have to think a lot harder about plot, which is, somewhat surprisingly, not necessarily the most important thing in a short story. You can actually get away with not thinking very much about the plot. I ended up having to learn to be a very different kind of writer entirely in epic fantasy, and sometimes when I'm switching between the two I have a hard time. I was joking with a writer friend that after working on my epic fantasy for a decade, when periodically I go back and write a short story in those 10 years, I almost forget how to write a short story. I often sit there and I'm like, "Only 5,000 words? That's not even enough to introduce one character. How is that possible?" Because when you're doing epic fantasy, that is how long it takes to introduce one character.

So 5,000 words to tell a whole story seems ridiculous to me. I have to relearn all the skills every time. The Armies of Those I Love is kind of interesting because it's really a novella, so it's longer than a typical short story but much, much, much shorter than novels. It gives me just enough space to introduce one character in depth and to tell one story about her in depth, which is really kind of cool. This is not a length that in traditional publishing is very popular but I feel works particularly well in audio format. I don't know how long the recording in the end is, but I think it's just about right for one to two sessions.

SD: That's really interesting. And as you were kind of describing that, I was thinking too of what's the difference then in the experience when you're listening to that in audio, and in a novel you get the sense that, you know, sit back, someone's telling you a story, someone's telling you about the world, but as you say in a short story, in a shorter format, the listener is kind of filling in a lot of those details. And I think that also works really well in audio and particularly well in this story, where you are having to imagine this world that's so unlike anything you currently live in. It does seem very well suited to the audio format, in my opinion.

KL: Yeah. It was a lot of fun to work at this length. I almost wish I got more opportunities to do it in the traditional short fiction market. This is not a length that gets a lot of attention just because, you know, magazines don't have enough space to publish many stories this long. On the other hand, this is not the length that works well as a stand-alone novel. It's almost perfect, really, for the audio and electronic markets.

SD: I love that. It gives you a little bit more freedom, I think.

Part 2

SD: We've been talking about audio, we’ve been talking about writing. You, in a way, have the experience of taking an author's words and interpreting it in that you're a translator as well. Can you tell me a little bit about what that's like? I imagine there's a lot of responsibility to it and interpretation.

KL: I think this is something that people don't often think about, which is the degree to which you give artists of different mediums the freedom to perform. Literary translation is really just a performing art. It's not very different from acting or playing music or anything like that where the original is the score or the script, and you have to actually perform. But the degree to which we allow performers freedom to deviate or to interpret or to construct new artworks is very different.

For example, those of you who are familiar with the stage know that there's a huge amount of freedom allowed when you're staging a play, especially something like Shakespeare. You really can take pretty much any sort of freedom you want. You can delete entire scenes or add all sorts of stuff if you want to. There's just a huge amount of freedom given to that kind of interpretation.

It is a performance to create a new piece of art based on another piece of art, and it just happens to be that our conventions are such that the degree of freedom allowed the performer is extremely small.

In literary translation, not so much, because there seems to be a huge amount of obsession over whether the translation is faithful or not, which I think is about the most foolish way to evaluate a piece of art. It will be like if you're going to listen to some famous musician performing Beethoven, and then your entire judgment is on how "faithful" quote unquote, that interpretation is, which all of us would think is absurd. That's not how you judge a piece of music. Nonetheless, that seems to be a lot of how people judge literary translation.

I just think we don't have the vocabulary and we don't seem to have a culture that allows us to really understand literary translation is actually a performing art, even though it is. So having put that all aside, I will say there does seem to be a little bit of a difference in the way we treat interpretations and translations from classical works versus contemporary works. If you're translating Homer or Confucius…or something like that, you are given a lot more freedom to perform versus if you're doing a contemporary writer.

And it's worth thinking about why it is. Why is it that we, as a culture, seem to give much more leeway to interpretations of classical old texts? Even something like the Bible, where accuracy would seem to be very important, but, in fact, we do give the translators a huge amount of more freedom than we do than if they were translating a contemporary work. I think it's worth thinking about why that is.…

Our conventional understanding of literary translation, especially in the contemporary age, because influences from things like Google Translate or other mechanical means of doing translation, we've really tried to take the art out of translation as much as possible. We really tried to treat translation as some kind of mechanistic, mapping of semantics from one space to another.

As a computer scientist, I understand why people think that way, but the reality, though, is literary translation is not that. It's not very interesting to think about it as a mechanistic mapping from one to the other. It is a performance to create a new piece of art based on another piece of art, and it just happens to be that our conventions are such that the degree of freedom allowed the performer is extremely small.

The performers have to do all they can with the very limited amount of freedom they have. Not all that different, really, in some ways from narrators for audiobooks. They also are, by convention, given extremely small amounts of freedom to interpret, and they have to do what they can with the limited tools available to them.

SD: That's such an interesting thing to think about too, the journey from a work in its original language to the translation, which is its own form of performing art, to the narration where the slightest inflection or accent can completely change a listener's experience of the story. I love thinking about that whole process that translated works have gone through to get to audio.

KL: Also another way to think about it is, there's the whole idea of potentials and specifics. Another way to think about that that I think may be enlightening to people is this: take something like, say a classic piece of work, say something by Jane Austen, okay? So you're going to find multiple audio versions of it. You'll listen to the different narrators, and obviously each of them interprets the passages differently and would speak a certain way... would say a certain line this way in this narration, and a different way in another narration. Mr. Knightley would say a certain line this way in this narration, and in another one a different way.

The original has an infinite number of translations, but the translator always takes that one particular interpretation and puts it onto the page, which itself contains the multitude of possible performances when taken to the audio format.

The point is, the original work and the pride and prejudice, or what have you, has infinite potential, infinite ways of reading, and the narration narrows that down to one particular interpretation. It's one performance. The original contains an infinity of performances, but the narration is one specific one. When you're talking about translation, it's the same thing. The original has an infinite number of translations, but the translator always takes that one particular interpretation and puts it onto the page, which itself contains the multitude of possible performances when taken to the audio format.

But I think that may be helpful, because oftentimes when we obsess over whether something's accurate or faithful, it's just not a very helpful way to understand it. It's much better to think about, "This is one interpretation." Of course it's faithful. All interpretations are faithful. But the question is, "Is this an interpretation that I enjoy? Are there other interpretations that would allow me to see other perspectives on the original?" That, to me, is the way that I like to evaluate translations and performances and think about how they change or not change my perspective on the original.

SD: That's a great way to think about it, and really gives you some thought as you read or listen to a story years later, even your interpretation in that moment might be different from the first time you've ever heard it. As we get to the end, I want to get into a little bit of what you're working on now. You are halfway through your Dandelion Dynasty series. I believe the third book is due out this summer, The Veiled Throne.

KL: This November. November.

SD: This November? Okay. So that's exciting. Can you tell us a little bit about what to expect there and how that's going?

KL: Sure. So The Dandelion Dynasty is this giant epic fantasy that, as I mentioned, it's over a million words now. The whole series actually is done. It's finished. The first two books are out, The Grace of Kings and The Wall of Storms, and they are available on Audible. Michael Kramer is the narrator and he does an amazing, amazing job with it.

The Veiled Thrones, which is the third book, and then Speaking Bones, the final book, they’re scheduled to come out in November of this year and then summer of next year. They were actually originally written as one book. It's just that the book was so long that my publishers were like, "There's just no way we can publish this as one book, because it's just too thick. There's no... the binding technology will not support it," which is not something I ever thought I would hear.

We just chopped it down the middle into two separate books. So that's how it is. This was originally conceived of as a trilogy and I wrote it as a trilogy, but because of the way the medium won't support what I wanted to do with this, it has to be the result.

I'm super excited about the series. It's definitely... The series as a whole, as I mentioned, I worked on it for a decade, and it's definitely the work that I'm most proud of. It's a little unusual, I think, in terms of what it is. You mentioned earlier that it's a silkpunk epic fantasy, and I think people often say, "Well, what does that mean? Well, what is it?" It's easy to define but very hard to explain. So I'll define it first and then I'll explain what I really meant by it.

Silkpunk is kind of like steampunk in the sense that steampunk is about taking the technology of Victorian era, England, and just extrapolate it out into a semifantastic, semitechnological feature. What would happen if you carried steam-based technology all the way to its logical conclusion and it extended out? Silkpunk is about taking the technology of East Asian antiquity. All sorts of machines built with bamboo feathers, animal sinew, wind, water power, all these classical pieces of East Asian engineering.

And you just take them to their semifantastic, semitechnological logical end, extend them out. Can you build computers with this sort of technology? Can you build earth-moving machinery this way? Can you build skyscrapers? Just extend it out. See what would happen. That's basically what it is. That's an easy way to imagine it.

But in practice, what I ended up doing was something a little bit different from how I even originally conceived of it. When I started writing the series, I just wanted to tell a fun epic fantasy. Your great hero's journey kind of story. That's what I wanted to do. But it ended up being nothing like that. It actually ended up being an epic fantasy that is about constitutionalism and what it means to have a national mythology. It's the same sort of thing I was talking about earlier about how each of us has our own personal mythologies, and the way we understand the world is through layers of stories that have given concrete meaning to abstract words and how we then strive to become the heroes of other people's personal mythologies.

Well, the epic fantasy is just taking that but elevating to the level of entire nations, because it turns out that nations also have their own personal mythologies and their foundational stories—stories that people tell themselves to explain how they came to be, how they're different from every other people across time and space, how they are distinct, how they're special, and what allows them to declare that they have dreams worthy of being pursued. Whether it's the Aeneid for Augustine Rome or our stories about the founding fathers, the American Dream, or Britannia law which ruled the waves. Every nation has its own foundational story. It's mythology that really becomes much more important than their overt institutions.

So, to go back to what I was saying earlier, right? I have the theory that good stories are more important than good institutions. Because I was trained as a lawyer with a special interest in constitutionalism, I looked into this quite a lot. You have countries with beautiful constitutions, perfectly drafted, very modern, full of insights from the best constitutional scholars on the planet, but these countries do not have stable democracies. They, in fact, lurch from crisis to crisis to...from coup to emergency, to martial law, all the time. Revolutions, they just... They're not stable.

You have other countries with no written constitution at all. Nonetheless, they're very stable, they function well as democracies. They try to solve their crises in nonviolent ways. So, why is that? My entire thesis, and what I'm trying to show in this epic fantasy, is the idea that a good national mythology, one that is supple, one that is responsive, one that inspires diverse groups to feel that they can all have a voice in the future of the political entity, that they can all share in the future, that kind of story is far more important as a constitution than the piece of text.

Constitutions are not merely institutions, because institutions are easy to manipulate. But stories are much harder. If you have the right story, a story that people can rally behind, you can patch up and route around gaps and lapses and mistakes in the institutions. But institutions will never save. The best-designed bureaucracies will never save people if they don't have a story that they can actually rally behind.

I have the theory that good stories are more important than good institutions.

I feel a lot of times when we're talking about contemporary politics, let's say the crises we're facing in the US right now, well, what we're really facing is not so much failure of institution. Oftentimes when we talk about reform, we talk about technocratic solutions to constitutional reform. You know, let's change the way the Supreme Court is organized. Let's change the way we have... DC is not a state. We keep on trying to fix things through these technocratic solutions. I think it's the wrong focus.

I think it's much more about, can we come up with a new narrative? Can we renew the American Dream and renew the American narrative so that all those who had been excluded and silenced and oppressed now feel like they have a voice in this chorus, that they have the right place in this story, that they can view the story as their own and can actually carry forward the story? A constitution is not a stable thing. It has to be reconstituted by every generation to respond to new needs, new desires, new voices, new challenges. The story is never finished because every new generation has to add to that national mythology.

All of that is what The Dandelion Dynasty is actually about. It's an epic fantasy whose main character is not an individual, but a whole people. It's about this whole people's attempt to renew their constituted national narrative to meet new challenges, to accommodate the sins of history, and to bring forth a new future in which everyone can feel that they have a voice and a stake.

Working on the series was how I managed to survive through the pandemic and a lot of the terrible things that have been going on in the real world. I'm just really excited to share the result because I have a lot of hope in the future, and my series is full of hope in the same way that The Armies of Those I Love is like that. It's a story in a post-post-apocalyptic world, but it's full of hope. It's about how everybody can, in fact, make a difference, that there is no need to give in no matter how terrible and hopeless it may seem, because we were loved and we deserve to be loved, and we deserve to love others.

SD: I love that message, and I love that it all comes back to storytelling and narrative and who gets a say in the narrative. And, of course, Michael Kramer is fantastic. As you were talking about the size the book would be, I have to admit I was trying to do the math of how long the audiobook would be too. That's just how my brain is wired. I'll figure out that math, but I'm sure it would be a long one. I'm sure listeners appreciate the series though.

KL: I think so. I put all of myself into it. This is the work in which I put all of myself into. Everything I love is in there. My love of constitutions and constitutionalism, my obsession with institutional reform, my background as a computer scientist. I actually tried to build a computer out of bamboo and feathers, so listeners will enjoy that part. I actually tried to prototype some of this stuff to see if it's actually doable. I can't say that I got to the... got them to the point where they're production ready, but I have prototypes that will function, and it was really a lot of fun when you can work on a book in which you can put everything you love and everything you geek out about into it. So that's what I did.

SD: That's great. That is commitment to your work and your writing. I love it. Well, Ken, thank you so, so much for spending this time with me today and chatting with me. For Audible listeners, you can listen to The Armies of Those I Love, Ken's new story, right here on Audible Plus, and, of course, you can get all of Ken's other wonderful books here on Audible. Thank you so much, Ken.

KL: Thank you so much, Sam. It's a real pleasure.