Note: Text has been edited and may not match audio exactly.

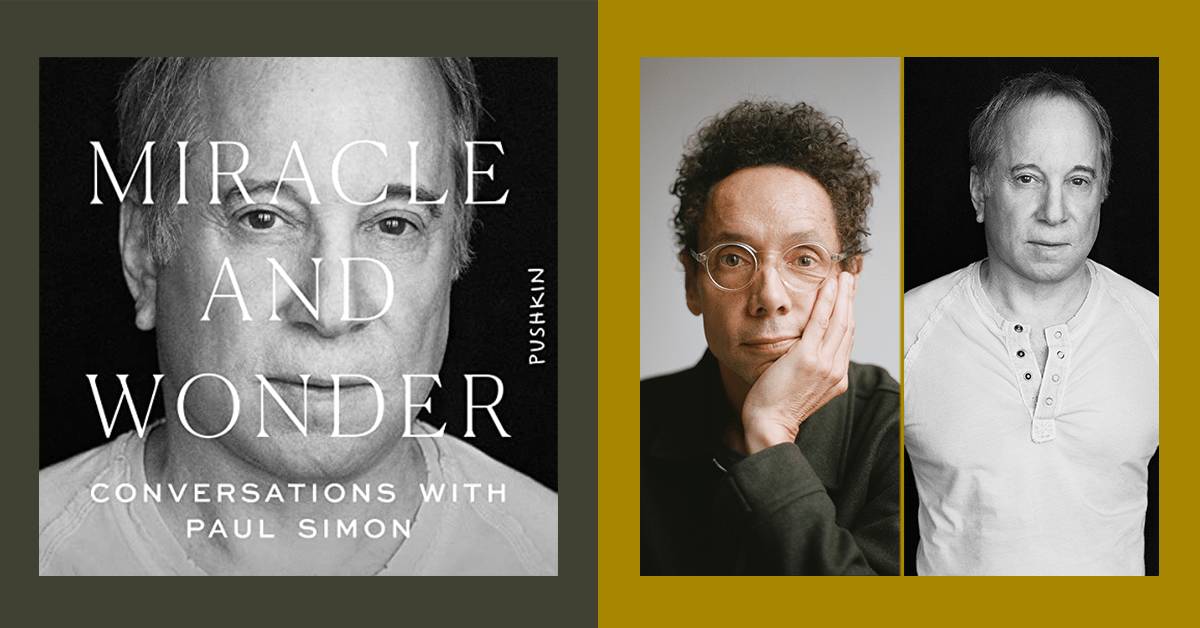

Christina Harcar: Hello. I'm Audible Editor Christina Harcar, and I'm delighted to be speaking today with Malcolm Gladwell and Paul Simon about Miracle and Wonder. Miracle and Wonder is the perfectly named audiobook about Paul Simon's lifetime of songwriting and artistry, and it's based upon conversations with him and Malcolm Gladwell, and Malcolm's lifelong friend and musician Bruce Headlam. Welcome to Audible, gentlemen.

Malcolm Gladwell: Thank you.

Paul Simon: Hi, Christina, and hi, Malcolm.

MG: Hi.

CH: So, Malcolm, the last time we spoke it was around the publication of Talking to Strangers in the relatively early days of Pushkin Industries. And as a longtime listener, I believe that Miracle and Wonder is a new high watermark for you and for Pushkin. Can you tell us a bit about how this audiobook got made?

MG: Well, I had always thought that stories about musicians were obviously the perfect vehicle for an audiobook, right? So, right from the beginning of Pushkin we wanted to do books with musicians, and I had a conversation with Jody Gerson at Universal. I said, “Well, who would be the best person to start with?” And she said, “Paul Simon.” And I said, “Sure.” And that was the beginning of it. We needed someone who could talk as well as play. Not everyone can talk about what they do in a compelling fashion, and there's so many ideas and thoughts and substance in Paul's music that it's the perfect thing to tease apart in a book like this.

CH: Yes. And one of the many, many engaging facets of this audiobook, Malcolm, was actually to be able to hear your delight to be hanging out in the studio with Paul while he was talking about this stuff. So looking back, what was your favorite musical moment of all of the conversations that went into this audio?

MG: Oh wow. There were so many. I liked it when Paul was playing for us the music of his youth, the songs he grew up with. I just thought that was a window into how his own tastes evolved and where his own creativity came from. That was just really kind of illuminating. I've been listening to his music my whole life, but the idea that doo-wop was central, for example, to his early musical development was just interesting to me. That's not a connection I would've made naturally. But it turns out to be incredibly important.

CH: Paul, I actually was going to ask you a very similar question, which is, how did it feel for you to pull back the curtain on songwriting? How did it feel to talk about this thing that you do so well and so often and so naturally?

PS: It was a relief to be able to address the subject and not have to simply rely on words to describe it, but to be able to show the sounds and say it was this particular sound that I fell in love with, or when I heard this rhythm and I was 13, I liked it and I had no idea that it was a Louisiana rhythm. I haven't changed my mind about those sounds. I've expanded my palette of sounds that I like, but I'm still passionate about the earlier sounds that I like. So when I've been interviewed I can't really show why I loved a certain sound that I heard when I was 14 years old. But in audio I can.

"We want the listener to feel like they're in the room." - Malcolm Gladwell

Another thing is, when I'm actually talking about the craft of songwriting, if I wanted to say there's a conversation that's going on between the melody, the harmony, and the words in book form, you can't really express the one part of the conversation. But if I could pick up my guitar and say, "I use this chord in this particular way," now that's a subject that I've never felt that I adequately explained in a print interview.

CH: Wow. As someone who's listened to this, I thank you not just for that great answer, which hits the nail on the head from my experience about what it's like to listen to this audiobook, but also for sharing those stories which are so valuable. I love what you said about knowing the sound that you were in love with and that you've just picked up different ways to do it. I remember when Graceland came out, and it felt totally new and energizing to listen to it as someone who knew your work before. And Miracle and Wonder really goes into the richness of that collaborative experience for you and how the learning and musicianship went both ways on your trips to Johannesburg. So could you talk a little bit about that experience please, Paul?

PS: I would say that Graceland had to be one of the great learning experiences of my career. I had briefly in my past recorded with musicians from different cultures in their home country. "Mother and Child Reunion," for example, is a reggae song that was recorded in the studios in Jamaica where those musicians were making that music. When I was making the last Simon & Garfunkel album, Bridge Over Troubled Water, I was already a fan of ska music, which is a Jamaican predecessor to reggae. So I wanted to make a ska background to one of the songs on the Bridge Over Troubled Water album and the song was "Why Don't You Write Me."

So I said to the musicians that we were working with, "I wanna do this like ska.” And they said "Well, we don't know what ska sounds like." So I said, "Oh, okay. Well, let me play you a ska record." So I played it and they made notations and then they did their best to play ska. But it didn't sound right to me. And I remember thinking after a time, this is unfair to a musician. It's like asking somebody to write in somebody else's handwriting. So I realized then, if I want to do music that sounds like Jamaican music, I have to go to Jamaica.

But I had already done it once before on another song that was also on the Bridge Over Troubled Water album; that song was "El Condor Pasa." And that came from when I got a booking in Paris in 1964 and I played a variety show. It had quite a few other acts, and one of the other acts was this trio from Argentina called Los Incas, and they were playing Peruvian music. They were playing this song called "El Condor Pasa," and I just fell in love with it. It's so beautiful.

They gave me their album, and "El Condor Pasa" was one of the songs on the album. And I remember saying to Artie, "Why don't we just go and buy that track for 'El Condor Pasa' and I'll write lyrics to it, 'cause nobody could play it except them and the track is already perfect. So let's go and do that." And that's just what we did, and I wrote lyrics over it and we sang to it.

So that's really the first time that I said on record, popular music doesn't have to be from the United States. Graceland is an album that's entirely about that idea. If you liked a certain sound, you go to the musicians who played that sound, and in the case of Graceland, all but two of the tracks are performed by South African musicians.

I was put in touch with a producer, a South African producer named Hilton Rosenthal, and he said, "Do you know South African music?" And I said, "Not really. I just heard this one thing." And he said, "Would you like to hear examples of it?" And he sent me a bunch of albums and I listened to it and I thought that there was a way of connecting to that music. And the way that I heard that going back to '50s rock and roll, it sounded to me like it had a cousin in American rhythm and blues from the '50s. So when I went there, I was thinking, I can relate to that aspect of it. It sounds like the '50s.

My first couple of sessions weren't successful. But after like two days a band of musicians came in and they were great, and we cut Graceland, and the "Boy in the Bubble" and four or five of the songs were actually recorded in South Africa.

So the idea that going to the musicians who played the music that you want as your context for the words and melodies proved to be correct.

CH: Wow. That is a great answer and so generous. Thank you. There's an authenticity of experience that you keep trying to get back to that you find with these other musicians. I mean, the entire audiobook is a collaboration and your stories are about how you collaborate with these different people. So my question is, while you were collaborating and enjoying each other's company, what do you want listeners to take away from these conversations?

MG: Well, one was just how much fun it was. When I gave Paul a draft of the book to listen to, we were still doing the editing, and he gave a comment on the chapter about Graceland actually. And he said, "My one criticism of it is, it doesn't communicate how much joy there was in making that album." And it was a very, very good note, because the intent of the book is to communicate how much joy there is in Paul's music. And we went back and we fixed the chapter, and now it's a lot clearer. We want the listener to feel like they're in the room and feel like they're having this incredible time with one of their favorite musicians. And that's really all.

CH: That's great. Paul, do you agree with Malcolm that that's what you want people to take away?

PS: Yes, I do agree with that, although I didn't really think that I had any particular thing that I wanted people to take away other than something that's enjoyable. But the collaborative aspect of working with Malcolm… Well, first of all, I was already a fan of his work. I like the way he thought and it was provocative, so I was looking forward to the conversations and I knew I would be speaking with a fellow artist, and often he would come and ask me a question from an angle that was, I guess I could say, unexpected. And that was fun for me too, because one of my strong beliefs is that the listener is the final collaborator on the song. The song isn't finished until the listener hears it, and that's the final song.

Any good art is open and available to a lot of different approaches. And although the artist may have a specific way of expressing it, it goes beyond what the artist knows himself or herself. And because Malcolm has that kind of brain and thinking we were able to let our conversations flow into conversations about writing and thinking, which made it much more fun for me.

He would come in and he'd say, "I really like this song 'Tenderness' from your second solo album." And then I thought, yeah, that was a good song. I never performed it, it wasn't a hit. But it was a good song. And then when he picked it up, he said, "There are elements in that that are in a lot of your writing." There was a certain aspect of my personality that comes through, and that song was a good example of it.

"One of my strong beliefs is that the listener is the final collaborator on the song." - Paul Simon

MG: We were a threesome because Bruce Headlam, my old friend, joined us. And Bruce knows a lot more about music than I do, so he had a different kind of interaction with Paul than I did. Bruce and Paul could dive deep into the specifics of music, and I was more interested in themes. I always think conversational triads are the most interesting, you know?

The book is filled with these cameos where we made a list with Paul of other musicians who he either worked with or who admired him, and we interviewed them, and that was fun because you got to hear Sting talk about the song "America," and it just gives you a whole new understanding of that particular bit of music, you know? And to see the enormous affection these other musicians have for Paul, I just thought that was lovely.

CH: I think it's lovely too, and it actually does come across. I did feel like I was there in the studio with you and I felt very ebullient at times, and there were a couple of times I teared up with the profundity of it.

PS: Bruce being there enabled me to go from what I was thinking about with the lyrics and how I was using the lyrics rhythmically and sonically, and turn to Bruce and say, I chose this harmonic combination which maybe underlined what I was saying in the lyrics in one particular way. Or maybe I would use it ironically, so that the entire meaning of what's going on with the song is not simply from the lyrics; it's also from what rhythms and what harmonies and what melodies you choose. A lot of music sometimes just feels like a big ol' return to your childhood, you know? There's something in there that you heard before you were aware that you could love what you heard, and it stayed.

And then as you become older and more experienced, you add layers over that almost to the point where you think that's obscured. But it isn't. The memory of certain sounds remains, and I would use those sounds to evoke the feelings that they evoked in me. So when it came to explaining that, I could turn to Bruce and say, for example, I love the sound of a drone in Celtic music. But you also hear a drone in Appalachian music, in country music. And the drone is also there in Asian music. It's there in Brazilian music. There's something about a drone that seems to be a worldwide language. So many cultures love it.

And to be able to talk about what that might be, that maybe it comes from the overtone series. The difference between hitting a C on a piano and hitting a C on a sine wave is that the overtones exist on the piano. They don't exist in the sine wave. Bruce understood what I was talking about with the overtone series, so I could speculate that maybe that was why the drone was so universally embraced, because it maybe it had something to do with physics.

Most of the time in tonal music they don't play with overtones that much. But in certain avenues of music, like microtonal music, the composer might alter the overtone series. And that alters the sound of what you're playing. Now, if you use that in a song, and I did use that in several songs. The first one that comes to my mind is a song called "Insomniac's Lullaby," where I used these instruments that were invented by this composer, Harry Partch. And Harry Partch said essentially that the European idea that an octave is divided into 12 notes is purely just a European opinion. It's not a fact. It's an opinion. He thinks the octave is divided into 30-some-odd different tones. Bruce knows what I'm talking about because he's a musician. When I go into this, I sort of lose three-quarters of the listeners because they don't know what I'm talking about, which is exactly why Bruce was great.

CH: When you said you lose listeners, you're saying that the "trialog" [of lyrics, melody, and harmony and rhythm], a phrase you coined, allowed you to open up and play with these guys in words and music.

PS: Yeah.

CH: I loved that that was a vehicle for your generosity. You want to hand people the feeling of this song. It's so cool.

PS: Well, that's kind of you to describe it as generosity. It's really just getting into a conversation that I have all the time with myself. I think about songwriting probably more than I think about anything else in my life. So by the time you get up to be, I'm shocked to say, 80 years old, and that's what you've been thinking about since you're 13, it's just sort of a metaphor for the universe. And the same is true in all the arts, and the same is true in science, and the same is true in repairing a car, or hitting a line drive perfectly with a ball and a bat.

But you're allowed to be obsessive because that's what you're obsessed about, you know? I once had a recording with Brian Eno on my album called Surprise. And I was doing a thing over and over again, and I could see that he was kind of restless in the studio, and I said, "Does it bother you that I'm doing this over and over again?" And he said, "Yeah. It kinda drives me crazy." I said, "Well, all right. You know what? Go out and have a cup of tea and I'll just do this by myself for a while."

Then later on at dinner, I said, "Well, do you think I'm compulsive?" And he said, "Definitely." And I said, "I agree. I agree. I think you're compulsive as well when it comes to the synthesizer sounds that you're working on. You can spend an hour working on a sound." The idea of being bored, it's just not even what goes on with artists. Things just go on for as long as you're engaged in them.

And to be able to talk about those aspects of the creative process that apply to songwriting, that was part of the reason that I wanted to do this book. Because otherwise I could say, maybe an artist shouldn't do anything but just reveal their work and that's it. But in this case the opportunity to talk about things with another writer and another musician, it was the first time that I ever had that opportunity, so that's why I was drawn to the project.

CH: I'm really glad that you had a good time too. So, Malcolm, I wanted to ask you a question because I was absolutely, as the Brits say, gobsmacked by one of the phrases you used in the book. You were talking about one particular aspect of Paul's talent, which is this idea that he knows exactly what he wants and that he's spending a lifetime teasing it out of his own craft. And you were talking about the phrase "memory as an engine of taste," and I just thought that is so true. It made me think about my own work differently. I wanted to know, do you think that there's a self-development aspect of Miracle and Wonder or of studying artists? I mean, did you intend it to be there or is just part of the general joy?

MG: It's funny. The filmmaker Ron Howard has just written a book, and I interviewed him for a book event. And if you read his book, you realize that he has a specific memory for conversations and scenes and people. That was astonishing to me. I mean, he's close to 70, but he could talk about something his mother told him when he was six as if it happened yesterday.

"I've long felt that memory plays an undertheorized role in the creative process." - Malcolm Gladwell

And I had the same reaction when Paul would talk about music. It reinforced this idea that sort of emerged out of Miracle and Wonder of the role that memory plays in creativity and in taste. I mean, Ron Howard is actually in some ways similar to Paul in that he's had a very, very, very long window in the center of the zeitgeist. He's made very popular movies for a long time, unlike a lot of others. And like Paul, his memory allows him to draw on an extraordinarily wide range of experiences, voices, characters, because it's all intact in his head. I've long felt that memory plays an undertheorized role in the creative process.

CH: In my experience dealing with great artists also goes hand in hand with a deep memory for a thing. The phrase “they've often forgotten more than the rest of us has learned” can really be true.

So I have an open-ended question for either of you or both of you. Is there anything else you would like listeners to know about Miracle and Wonder that we haven't already touched upon?

MG: So I'm someone who had listened to virtually all of Paul's music. Some of it, many, many, many times, before I had even dreamt of this project. But there was still an extraordinary number of surprises in the conversation. So the first thing I would say is that, even if you are a fan of Paul's music, there's so much more to find out. A surprising amount to find out. You know, Paul's really good company. It's a really fun hang. You can't say that of every famous artist. I don't know whether I would want to spend seven hours with absolutely every rock star of the last 50 years.

PS: That's nice of you to say, Malcolm. I appreciate it. Thank you. I enjoyed it too. It was fun.

CH: Well, all I have to say is, both of you, heartfelt thanks for your time today and the candor of your answers and, most of all, for a unique and truly meaningful audiobook. Listeners, you can download Miracle and Wonder: Conversations with Paul Simon right now at Audible.com.