Note: Text has been edited and will not match audio exactly.

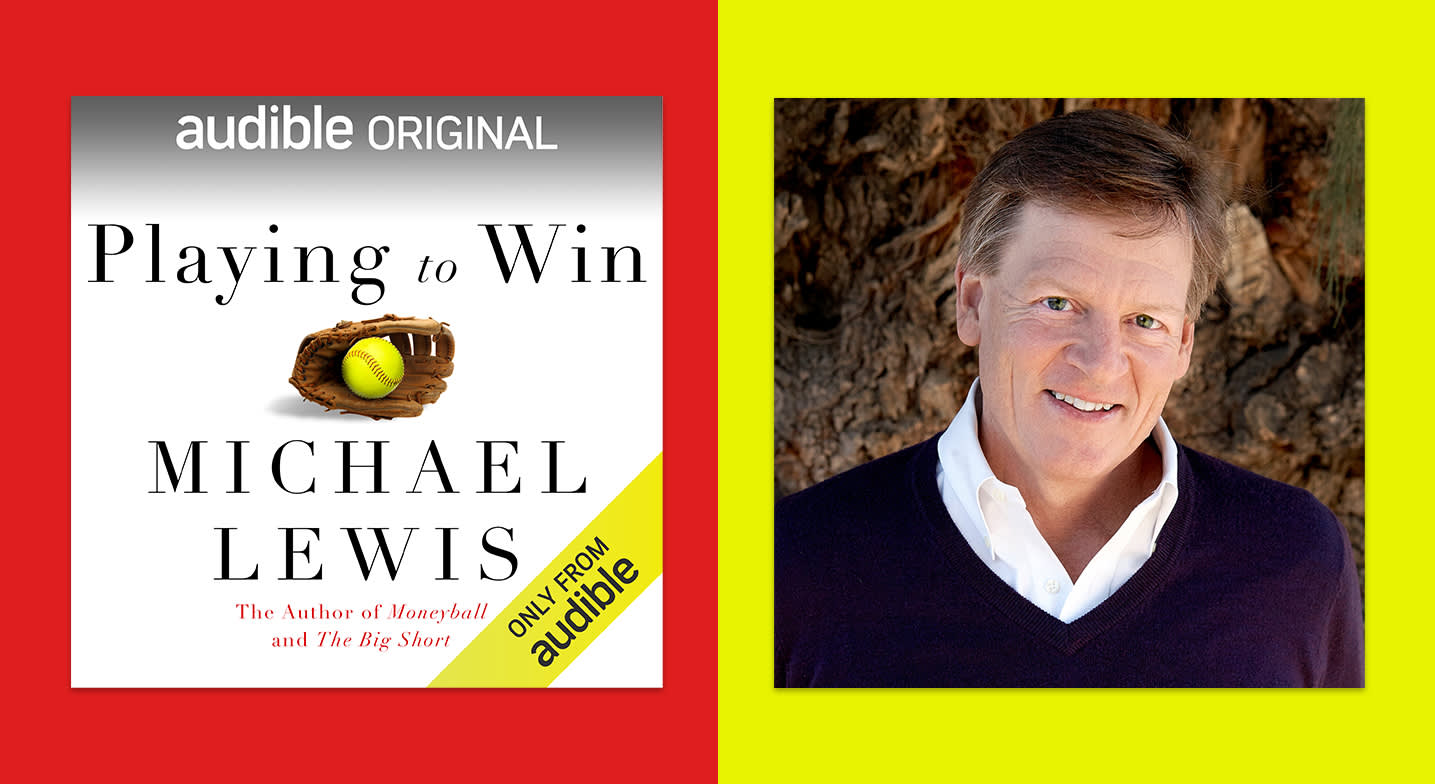

Kyle Souza: Hi. Audible Editor Kyle Souza here, and I have the pleasure of sitting down with Michael Lewis, author of literary and Hollywood sensations like Moneyball and The Big Short, but also a dear friend of Audible. His new Audible Original, Playing to Win, is a fantastic rumination on his own experience with youth travel sports, softball to be specific, and how these after-school leagues have become big business, with more than a few unintended consequences for everybody involved. So let's get into it. Welcome, Michael. It's nice to have you here.

Michael Lewis: Thank you, Kyle. Good to see you.

KS: Appreciate it. So I'll just jump right in. You've written a lot about what the layperson would call a scam of some form, and in particular how people set up certain financial systems to take advantage of others, or just to make money in general. Playing to Win operates within that framework, but is a more personal story than some of your other writings. How did it feel writing and then recording about you and your family? You don't mince words. You were a little scammed by the youth sports industrial complex. You're on the other end of the scam this time, I feel like.

ML: I am totally on the other end of the scam, but I don't think of it as a conscious scam. It's this thing that has arisen in the middle of American life. I'll just describe what happened, because I think the way I drifted into [this] is the way that most parents drift into it. I wasn't a professional athlete; I didn't have any ambition for my children to become professional athletes. My wife has absolutely no interest in sports, like, negative interest in sports. So when my two daughters—my first daughter was six years old—there was this little softball league in the park next to us. It was adorable, my wife thought, "This is the way we get Michael involved in parenting." I did play sports. "This is the one thing he's really interested in. He could [go] down there and coach them."

"...In response to a parent's natural desire to see his child succeed, and in response to the natural pleasure that one takes from playing a sport, there has been created this machine."

So that's what I did. I became my daughter's softball coach and I helped run the little local softball league and so on and so forth. But what happens, and this happens in every sport, if your kids are any good and they're ambitious, you start to realize that—there's this cute little local softball league, and it was in Berkeley, California, so you can imagine what the cute little softball league looks like in Berkeley, California. No one's allowed to win more than half their games. If you coach your team to a perfect season, you're fired the next year. I'm totally serious. The goal is to manage to a .500 record and to make everybody feel like they played the same amount and that striking out is almost as great as hitting a home run kind of thing.

Which is all fine. It has its place in the world. But of course, it is a competitive sport, and so people are trying and you can't help but notice that some have more aptitude than the others. The ones that are good, and my daughters were good, they want to see where they can go. So on the side of this little softball league has been grafted what's called a travel team. The travel team, in Berkeley terms, is actually no kind of travel team at all. We drive to Stockton and Modesto and maybe to Tahoe, it's all drives. 4

You realize first that you suck and that you're going to get killed every time. Seriously, the first year we were involved with it, my daughter's team goes like one in 40, and they're mercy-ruled after three innings over and over and over. So then what happens? The parents and the kids either fold their tents and go home, or they say, "We're going to figure out how to win." So we said, "We're going to figure out how to win." My wife goes along with this for a while, because this looks like, from her perspective, it looks like active parenting. Like all of a sudden I'm a dad, really doing stuff. I'm off with the girls all the time and she has all this free time. So it's happy, it's happy. At this point, it's all very happy.

But then what happens is I get more and more excited about how good we're getting, and I start this plot and scheme about how we're going to get better and better…. I start hiring coaches from the Cal women's softball team, and at one point, we had the best hitter and the best pitcher in the country coaching the girls…. Then what happens is, if they're that good they start to realize that this thing we're doing that's called travel softball actually isn't the real deal, that we're playing in a pretty small pool still, it's mostly Northern California, it's all just drives. And these other teams, they're mythical creatures, we never see them, and that’s where the very best players are. If you want to move on with your softball career, like maybe have a chance of playing in college, you need to go to one of those. Now, I have no idea what these things are. At this point, my wife wants to just shut it down. "We're not going to go drive an hour and a half away every day for practice to play for some strange team with a bunch of strangers." But it's too late, because the girls are now self-identified as softball players.

The main character is my middle child named Dixie. So Dixie goes and makes this team, which is a wonderful team called the California Nuggets, and before long she is spending $20,000 a year, or I am, on planes, hotel rooms, travel ball fees, equipment. And her schedule, I kid you not, if you just look at her schedule like you didn't know who it was, you just saw this is this human being's schedule, where they're spending nights, you'd see that in a given year, she had spent 35 nights in hotel rooms and had been in 12 different states—you would have thought she was a traveling salesperson for some ambitious midsize corporation. Not a 14- or 15-year-old girl.

Well, all of a sudden, you're in this world that is expensive every which way, and it’s filtering kids and families partly for the expense of it, so that it isn't a rich person's world, because people play softball, it isn't a rich person's sport. It's not lacrosse. It's a really blue-collar kind of middle-class sport, so you've got these families being stretched, I mean stretched beyond belief, to pay for all this stuff. On the other side of it, you have, not the team so much, because the teams are actually kind of like scraping along, but the tournament organizers who organize these places where the kids play for the benefit of college coaches.

Those people are making not thousands of dollars, but millions of dollars. We can pick apart the scam one way or another, but the mechanism, what has happened in the country is essentially in response to a parent's natural desire to see his child succeed, and in response to the natural pleasure that one takes from playing a sport, there has been created this machine. And the machine is aimed at prizes, and the prizes are places in colleges and college scholarships based on your ability to play this sport, and there are all these toll takers along the way to get to that. It has happened just over the last 20 years, this is a new thing in American life….

The people who have analyzed the market will tell you that the dollars spent in the youth sports market in America today make it a bigger market than all of the professional sports combined. It's tens of billions of dollars. You have stories coming out of it like, a single volleyball tournament organizer in a single weekend will net, not gross, net more than a million dollars for his three-day tournament.

I didn't discover it as a writer. A writer might have said, "What are children doing these days? What's happened to sports?" And go investigate. I got sucked in, and in the end, there are great pleasures and benefits and all the rest to it, but it is like a world that's partly undescribed. People are living this and caring about it more than anything in their lives, and nobody's really talking about it, or writing about it any way. They do talk about it if you sit down with another parent, or any parent, and that parent has a kid who is an athlete and their whole family life is structured around that kid's athletic life. That's all they'll talk about.

But it hasn't formally entered the public conversation, and that interested me. So I thought, take my own experience, try to describe this bizarre thing we went through, for which my wife still has not forgiven me. She says two things that are, I think, partly true. One is, "You, Michael, your brain chemicals change when you walk into one of those softball fields. You are not the guy I met when I first met you." But the second thing she says is, she wonders what our lives would have been like if every weekend, but for a couple of months in the winter, every weekend we weren't on some airplane or driving great, great distances for the sake of one child's softball career.

It really ended up being the structure of our life, which is an incredible thing, especially given that, if I had a son who was a big-time football player, maybe we could use as an economic, a financial proposition, we could justify this. He'd get a college scholarship and go to school for free, play in the NFL and make a whole lots of millions of dollars. That's one thing. But softball? For one, there aren't that many scholarships, and the girls who get them, they tend to get partial scholarships to places. For two, once they get to the school where they're playing, if they're playing big-time softball, they don't get to go to the school. They're too busy being professional softball players at the school. So their education takes a big blow. Three, when they get out of the school, it's not like there's money to be made in softball. There isn't, unless you organize tournaments for the kids.

KS: Yes, there you go, unless you turn into the organizer.

ML: It's like if you had the Gold Rush in California without the gold. It’s like, imagine everything happens and there's a rumor there's gold, and all the people that run up into the hills and buy blue jeans and miner's picks and all the rest, this is a booming activity, but actually no gold. That's what it felt like.

KS: That's interesting. Much of what you talk about in the book is the relation to college scholarships, and you talk a lot about Title IX and the link between this youth industrial sports complex and Title IX, and both of their impacts on college admissions. A little bit of a two-part question, but do you think we need to revisit Title IX at all, and do you think that there's a way out of some of these negative impacts that are caused by this kind of sports machine and what it means for scholarships and admissions percentages? There's a national conversation around systematic racism, and as it relates to sports, do you think that there's a way to fix some of the negative impact from Title IX and what youth sports has done to the pool of money that's available for scholarships in general, just spots for admission?

ML: So I would say Title IX is one of the great things that has happened in American life. What Title IX did was to make available to girls what was already happening to the boys, and make it available going forward. So everything I describe happening to my daughter happens only because girls are given equal access to sports. The same stuff is happening with boys, and if you didn't have Title IX, you'd just have it happening with boys and not girls. And I think they should all have the same experience.

What is worth looking into, and what I find, the more I back away from it, intriguing and a little strange is the relationship of college admissions to athletes. All right, University of Alabama, let's just accept that part of this enterprise is not an educational enterprise in the conventional sense, that it is a professional football team that's generating huge dollars for the University of Alabama. So I can understand the University of Alabama saying, "All right." As Bear Bryant once said—Bear Bryant was the coach of Alabama way back when he said, "We want to have a university the football team can be proud of."

"The people who have analyzed the market will tell you that the dollars spent in the youth sports market in America today make it a bigger market than all of the professional sports combined."

And that's kind of like as good as it gets there. So it's one thing for a school to compromise itself for the sake of athletics, its academic mission for the sake of athletics, when it's got this big business in athletics. But the vast majority of college sports are not revenue generating. And the university admissions across the spectrum, from the most elite schools down to the least, compromise their admissions for the sake of all these athletic programs to an extent that I found incredible. It worked to our advantage. I was looking at it from the point of view of someone who had a child, she was a really good student, but she was going to have her pick of schools because she could play softball for them, and without any of the angst of a normal college admissions process. She was going to get to the end of her junior year and call up one of a half a dozen softball coaches and say, "I'd like to come play for you." That coach was going to walk over to the admissions office that day, before senior year even started, and come back and say, "You've got to go through the formal application process, but we've never not let someone like you in. You're in."

That's so different from the ordinary thing. If you look at the numbers at Princeton, where I went, or Harvard or Williams or Amherst or any of these places, the numbers are brutal: 5% of the kids getting in, 7% of the kids getting in, whatever it is, 10%. But the real numbers are, what’s the admissions' rate for non-athletes? It's sort of like 3%, 2%, and the athletes have this golden ticket. What I don't understand is, why athletes as opposed to violinists or chess players? That's the big question. It's like, this is one form of human excellence that I admire greatly, but why is it privileged over all others? Why do we tilt the society so much in the direction of athletic accomplishment? Now maybe we should, maybe there are lessons learned about working on a team or dealing with physical pain and physical endurance and physical sacrifice that are just so important that the society really does need to encourage it to that extent. But we are unique in the world in doing this.

You go to Japan or to England or to France or to Thailand, they aren't designing their educational system around their athletic programs….

It all happens because people think this is going to get my kid an edge getting into college. It's not a completely rational calculation. One of the things that I could not help but notice was that parents who were spending $20,000 a year on their kid's softball career, starting at the age of 12, on the financial theory that it was all going to be worth it because they were going to get to go to college for free, or get to go to college subsidized, had they just put those $20,000 into a 529 college savings account, they'd have been twice as better off. They'd have come out way ahead.

So it isn't a totally rational calculation, but there's no question that what energizes the whole marketplace is the favoritism paid to athletes by the schools. When you go to—in my case softball, but as I say, it happens in all the sports—you go to one of these tournaments where the elite really are meeting, where it really is the best travel teams, and there were times where there were 50 and 60 college coaches watching my child play, it really is a marketplace that's been created by the college admissions process. So what do we do? Your questions are like, what do you do?...

College admissions? That's where I would attack it. I would say, "Let's all get together, colleges, and let's talk about whether, is this what we want our institutions to be?" Maybe it is, maybe we make it explicit and say, "Athletics is just more important than every other thing." But at least acknowledge it. At least acknowledge that we have favored this one aptitude in a really unusual way, and what does it mean?

KS: Kind of a follow-up to that, at the very end you mention that you're taking a walk with your daughter, she's at the liberal arts college that she's ended up choosing, she's going to play softball at, and it seems that you guys are both having a conversation or thinking relatively deeply about all the time and effort and energy that you've spent on this. I think her quote was...

ML: Let me say it. Because it was remarkable to me that what she was put through was extraordinary, it was really grueling. Think about what a child gives up for these careers at that age. No dates on weekends, no parties, it's like one thing after another. Doing your homework in your hotel room, the agony of defeat over and over. Also, the thrill of victory, but an incredibly competitive existence at a very young age.

After her final tournament, it was all done, she decided which offer from which coach meant the most to her; we were at that school. It's a sunny day, we're walking around an empty softball field, and I started to just list off all the things that she had missed. Just to say, "Dixie, was it worth it?" She just started smiling, and she says "Yeah, but look where it got me." This isn't an unhappy story from her point of view and my point of view. The experience for us was in a way wonderful, but we've come at it from a very odd position, of extreme privilege. Like, the money didn't matter to me. The biggest problem with growing up with having a family that has some money is the kids are soft, the kids don't ever force themselves to do anything.

This prevented that from happening. She had her ass kicked every day and got up and did it again. So she got toughened up in the process. It was perfect. And the one argument for going through this process that seems to me a rational argument is the privileged access it gives you to schools that have very low acceptance rates. So she got in, and the school she got into had a 6% acceptance rate. Maybe she'd have got in without playing softball, but she'd have been in a pool from which they selected 3% of the people and it would have been a crap shoot. It gave her process in a way you just wouldn't have had control. So from my point of view, it was probably money well spent. It wasn't a tragedy, but we're coming at it from extreme privilege.

The only part of it that I thought made sense was the sacrifices she had made, but [the fact] that she felt that way, that made me very proud of her. I could totally understand why a child wouldn't, so it was interesting just to hear that her takeaway was, "Yeah, it's a totally screwed up universe." She understands that, she saw it. She would see kids whose parents really could not afford to be there, sleeping in tents near the field because they couldn't afford a Holiday Inn or a Hampton Inn or a Motel 6. It was that kind of stuff. So for her, it was all great. The best American story is a tragedy with a happy ending, right? This was like a tragedy with a happy ending.

KS: Since you've now published the Original and everything, have you had any conversations with her? Does she feel any different in retrospect? Again, I'm not sure how recent this is, but the conversation that was the capstone of the book, have you had any conversations now that she's on the other side of getting into that college and I assume is on campus? I assume she then has no regrets, being the person who had to go through all of that to get to this happy ending, there's no retrospective second guessing, anything like that?

ML: So that conversation took place now a year and three quarters ago, a year and a half ago. She's not allowed back on her campus. Nobody's playing anything. However, she's still totally delighted with the school she's going to and her softball team has formed this social unit, it's virtual, that she adores already, and she can't imagine not playing. She's totally happy with it. In fact, her one complaint is the pandemic may kill a year of her softball career and her college. So we'll see, but no, she doesn't have any bitter aftertaste, none….

KS: For people who are just kind of starting out and might be into this world in the medium term and in the future, after writing and doing all this and being a part of it yourself, what would be your advice? Reflecting back on it, what would you tell other folks who may get involved in stuff? Because obviously, you guys have had a really great experience. It's turned out really wonderfully, but what would your advice be just overall? Things to look out for, what would be the Michael Lewis sage advice for parents who are getting involved in youth sports?

ML: I'll give you some don'ts and I'll give you some dos. Don't, don't, God help you, don't think of this as financially shrewd. You will never get your money back no matter how good your child is, unless they're like a professional basketball or football player. So just don't think of it that way. If you’re doing it with a view to the benefits of a college scholarship, the financial benefits, don't. That's a dumb reason. Don't take your child's performance personally. It kills the joy the child takes in it. There is a famous line that gets repeated over and over in the dark bowels of kids' sports, "the most unhappy moments in the child's career are the drive home after the game with their parent."

So do learn how to change the subject. If you're in the middle of a child's sports career, you need to be able to talk about things other than sports. You're there to divert attention away from whatever just happened, unless whatever just happened is just fantastic and if they want to dwell on that, that's fine. But often they don't. So their career is their career, and you're just the chauffeur. You're the chauffeur who is supposed to be entertaining and lighten the mood. I would say, in the very beginning, when a child is really young, it's really great for them to play all kinds of things. Best not to specialize.

Great, you push them into things, of course you do when they're six or seven or eight or nine years old, because they don't, right? They don't know that softball exists, they don't know that you play lacrosse, whatever. But there will come a moment, and you've got to do it more by feel than by any kind of rule, but I'd say it's sort of like 12, 13 years old where they've got to take the lead. You can't take the lead. You can't be pushing them onward and upward, because if they don't want to do it, it's just going to be miserable. I saw lots of parents and children have miserable years. They eventually got through, but they just need to have them. Because the child didn't want to be there, but the dad did.

It's not your job to give your child your ambition for them. The child has to have their own ambition in this world. In terms of navigating the sports world, the problem is there's no regulator. As I say, it's a totally unregulated marketplace. It's very hard to tell when you're going into it who really should be in charge of your child. It's nice if you can coach them yourself up to a point. I do think they benefit a lot from being released from their parents as coaches. It's like enough already, you've got to have to learn to deal with some other authority figure.

I would say, before you let your child go into any kind of travel organization, interview some people who are no longer with that organization, but who went through it, and find out what you can about them. Don't just go into it blindly, because there really are a lot of dysfunctional ones, and they can kill a natural love that the child has in doing something. That's a real problem.

Other pieces of advice: the big one is this, and this is my wife speaking: you may think you have some idea of what you're getting into if your child starts to become a serious athlete, but you don't. It is going to be consuming. So if you aren't as a family prepared to structure your life around some kid's sports, know that going in. Make it clear going in. Because what you don't want to do is have this child that takes to whatever it is, soccer, and they're really, really good, but you want to have a summer vacation. And you don't want them to go make themselves good and then kill their hopes and dreams. It really is very hard to be half in.

I think maybe the last thing is, this gets back to what's dysfunctional about this world, that everybody says, "It's so good for kids not to specialize." It makes them even better in, like, soccer if they're also playing lacrosse and basketball and some other things, cross training. You have pro athletes who say, "I'm better at what I do because I did other things." Steph Curry says, "I'm a better basketball player because I played soccer when I was a kid." I believe that's true, I think that's absolutely true. Unfortunately, the way the kids’ youth sports market is structured, you're not allowed to do that. My stud athlete, Dixie, my middle child, when she was 10 she was a really good soccer player too. Her soccer coach—it was a travel soccer team, more serious at that point than her softball team—said, "You can't play softball and be on this team. I need you to be year-round soccer."

And I remember her weeping in the office of the coach. I thought, why does this have to happen? But she said, "If I have to choose, I'm going to choose softball." She was angry and upset, and she should have been. This is something that if your child is going to be a serious athlete, you are going to confront. You're either going to find yourself a very lucky, happy situation where you've got some understanding coaches who say, "It's okay, you can do other things." Or you can muscle the situation around and just insist, but you're going to have to, because if you just let the market take your child, they will be specialized way too early….

It's hard to know when to let them start doing their own thing, without any kind of control from you. This is a microcosm of that. It's true in lots of ways, in lots of parts of their lives. But with sports, because it's every day and you're really involved and all the rest, especially when they're really little, it's very hard to let go. But you've got to figure out how to let go, and that's been for me the trickiest part, learning how to let go.

KS: I will keep that in mind. I have trouble letting go of my dog, so we'll see how that goes. Michael Lewis, thank you for being with us. Playing to Win is out now on Audible. We thank you for your time.

ML: Pleasure, Kyle.