Note: Text has been edited and may not match audio exactly.

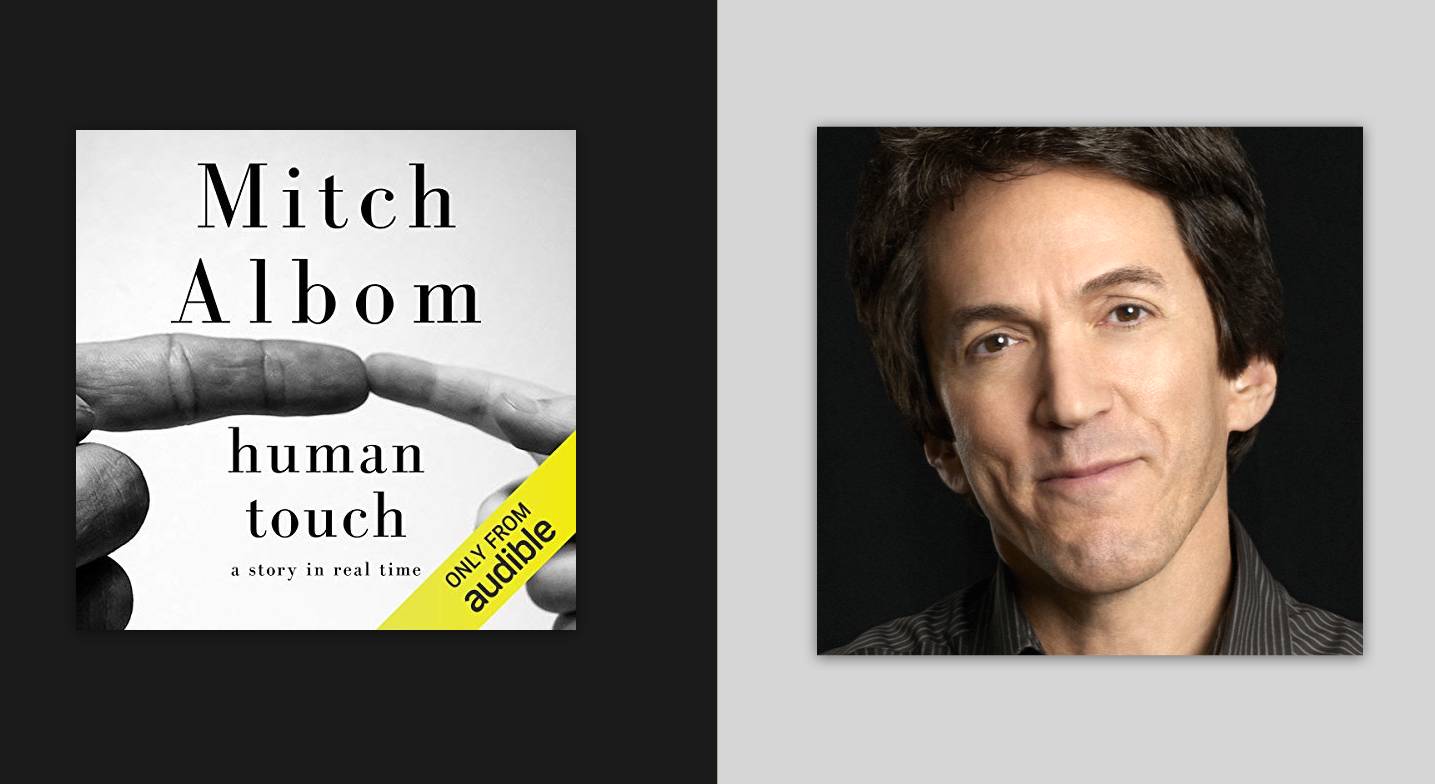

Abby West: Hi, I'm your Audible editor, Abby West, and I'm truly happy to be joined today by internationally bestselling author, Mitch Albom, who you know from the likes of Tuesdays with Morrie, The Five People You Meet in Heaven, and Finding Chika. But today we're going to talk about his newest offering, Human Touch, a serialized and fictionalized real-time exploration of how four families' lives intersect in a small Michigan town amidst the coronavirus pandemic. Welcome, Mitch.

Mitch Albom: Hi.

AW: Hi. I'm really glad to have you here and I'm excited to talk to you, not just because you're a pretty renowned author or even because what you're doing is a wonderful feat of storytelling, which we're definitely going to come back to talk about, but what makes this feel so real and so very much you is that you've made both the written version of Human Touch and the audio version free for everyone. And through that you've inspired donations to a project called Detroit Beats COVID-19, which has raised money to help poor families and first responders fight the virus in your hometown of Detroit.

Now your love for your hometown is pretty well-known and you've always shown a pretty strong moral compulsion over the years, but what drove you to this creative form of action so quickly while all this was developing around us?

MA: Well, I saw very early on that it was going to be bad here in Detroit. I have a number of charities I operate here in Detroit, so I'm constantly in contact with the poorer element of our city and I know how they live and I knew that given what was going on with Coronavirus [and] multi-generational households, households that had a lot of diabetes and high blood pressure, we were just going to be ground zero for that. And so I said, "Well, we're going to need some extraordinary effort here." And it would have to be something besides just, hey, we have a charity, give us some money to help operate it. Because I knew everybody would be doing that. And as people worried about the stock market, [which] was going down, and everyone's suddenly holding onto what they had [because] they were losing their jobs, that trying to get people to give money to charity was going to be 10 times tougher than it was in good times.

So I just sort of thought, honestly, Abby, "Well, what do I have to offer that someone will be interested in?" And the answer was pretty obvious. It's probably the only thing I have to offer that anyone's interested in: it’s my books. And so I thought, "Well, what if I were to write a book and give it away and just try to raise money for my city?" And ultimately, that's what we did. And we thought at the beginning, "Well, could we charge $2 for it or something every week?" And then I realized, well, there's a lot of people out there who don't have that, because I have readers around the world and not all of them are in a situation where they could afford to give anything. So we don't want to block them out.

So we said, "Let's just do the honor system and whoever has the means to make donations will. If they don't, they don't have to and nobody has to feel guilty about it because nobody will know, and meanwhile, I'll be providing something for people to read every week — or listen to every week — and that maybe will provide half an hour, 45 minutes of diversion every week." And so I kind of just jumped into it from [that]. Honestly, from the start of the idea to when I was writing was less than two weeks.

AW: Wow. That was fast.

MA: Yeah. Well, things happen fast in coronavirus world.

AW: This is true. In the time of developing the idea for this activation, were you also developing the idea for the story? I know this is so very different than how you normally work.

MA: Yeah. I usually think about a book for a couple of years before I even contemplate putting it into action. And I have a long, long list of books that I want to write that I'll never live enough years to do. Ideas aren't my problem. My problem is finding the time to execute them. So this was unusual for me to make a decision to do something in two weeks’ time. And all I really knew was kind of the title and a concept that, okay, there's no way you're going to have this whole story done in your head within two weeks’ time. Especially since with so much else going on about how do we set it up? How do we reach out to you at Audible? And all these kinds of things that take up time away from where you should be just sitting alone writing.

So I said, "Well, the best thing to do then is pick a setting that's sort of fluid and that you can develop a week at a time and change, because I knew things were going to change too." If I was going to do eight chapters, then that meant eight weeks’ worth of living in the coronavirus world. Who knew what was going to happen? Just to give you an example, when I started the book, they were still telling people that the only way you could get this is if someone's coughed or sneezed in your face and that masks were a bad idea and no one should be wearing them. And I mean, there was so much that we didn't know about it back then, and here I am starting to write. So if I had had everything plotted out, I would have looked pretty foolish.

I'm a very hopeful person ... and so my inspiration to sit down with any idea is to provide something that when people are done, it lifts them up a little bit and it lifts me up a little bit.

So I picked the street corner in a small town in Michigan, not at all that unlike where I live, and I said, "All right, I'm going to put four families on the street corner and I'm going to make them very close to one another," because that's how people are in Michigan if they live on a corner. They'll know all their neighbors. And this group of four families gets together and has meals. And I said, "I'll make it at the beginning that everybody's eating and they were hugging each other and kissing and sharing food and all the rest, because I know that's going to unravel." And then I just said, "All right, let me pick a cast of characters in these four families that will give me plot lines that I can take in different directions." I knew I wanted someone in the medical field. So, I have Greg, who's a doctor in an emergency room. I knew I wanted to express the prejudice and the anger that was unfairly being heaped upon Chinese Americans, so I made one a Chinese American young couple because I knew I'd have a vehicle for that.

I knew that faith was an interesting thing because people were already, when I started, talking about should we still have church services and is it proper? God will protect us, God won't protect us. So I made one of them a pastor and then I knew that the business world and commerce and food was going to be important so I made the fourth one, the owners of the local cider mill, which sells food and is able to stay open. And then I gave them all children and I knew at the very heart of it, I wanted a child to sort of be the hero of the story. And I can tell you why if you want to know a little bit later on. So I created this eight-year-old character named Little Moses, and he turns out to be the focal point of the whole story as it goes on — an unlikely hero, but I knew that he would play an integral role. And then I just sort of dove into that corner figuratively and literally, and began writing.

AW: I love that. And I have an idea of why you chose your young hero, and we'll talk about that a little bit more. But you said that you were writing this not only to raise money but also to give people a little bit of hope. What have you learned from this experience? What has it given to you?

MA: Well, I'm glad that I called the story Human Touch. We're a very huggy family, and people. Everybody we meet gets greeted with a hug and our family kisses and all that. And I already was seeing before I started writing, people were coming to the door and [saying] back up. And blow you a kiss and do an air hug. And I thought, "Boy, this is going to get old very fast. People are going to miss this." And I knew that human contact would be a very critical part of how we change as a society. And so I wanted to make the story reflect that. And that's why Little Moses, who is somehow immune to all of this, becomes this heroic figure, not only because of what happened to him plot-wise, but that he senses that people need to be held and touched. And so he goes from house to house where people are sick and sneaks in and lets them hug him and hold him, or hold his hand or whatever, just because he instinctively knows that that's a healing thing.

And that goes all the way back to Tuesdays With Morrie, and my time with Morrie Schwartz. And towards the end of his life, I had to hold this hand, rub his feet. I always had to be in physical contact with him. And I said, why is it so important that I'm always holding you or touching you all the time? And he said, "Well, Mitch, when you're a baby and you come into the world, what does a baby crave more than anything? What does it cry for? It needs to be held and touched and comforted, right?" I said, "Yeah." He said, "Well, I'll let you in on a little secret. When you're dying, it's the same thing. That's all you want, is to be held and touched and comforted." And he said, "The mystery to me is why in between the coming and the going, we don't realize that that's what we need as well."

So I never forgot that lesson and I knew that that was going to be critical, and it has proven to be. To answer your question, I think that whole thing about just not being able to be with the people that we care about, whether it's in just a simple setting like a dinner or whether it's in a tragic thing like a funeral, where you can't attend your own father's funeral, that whole thing has just brought out that there is nothing more important than human contact and the way that we relate to one another. And I always kind of suspected that I guess, because of my time with Morrie and other things, but it really was driven home during this coronavirus thing.

AW: Yes. You drove that home so beautifully with the character, Greg, walking in to the hospital room as a nurse allowed a family to say goodbye to the father who was dying. That has been one of the more heart-breaking things to me during all of this, that people cannot be with their loved ones at the end of their life. That's just really tragic.

MA: It's brutal.

AW: It is. You also mention that you are in touch with the poor and disenfranchised a lot in Detroit, but that's not just the only place. You have your Have Faith Haiti organization in Haiti where you do a lot of work. I suspect that played a role into you teeing up your hero in the story.

MA: Well, yeah. So I have an orphanage that I operate in Haiti and have for the last 10 years. Right after the earthquake, I went down. I ended up taking over this place and, unbeknownst to me, ended up running it and admitting 46 new children over the years. And we have 52 kids total, and they are, besides my wife and my immediate family here, they are the most important things in my life and most important people. And there's one little boy, whose name is Knox, who we took in. He had a tragic story. He was left to die under a tree when he was a few weeks old and he would have died there except that a woman happened to discover him, heard him crying. She was walking through the woods and she heard him crying. She found him and she picked him up and raced him to the police and the police said to her, "What did you pick him up for? Now we have to do paperwork."

AW: Oh my goodness.

My reading of the audiobooks began almost out of necessity because when I wrote Tuesdays with Morrie, which was the first book I think that we did an Audible book on, nobody wanted to do it.

MA: Which is kind of the way it's handled in Haiti. And so she got scared and she grabbed him and ran away and tried to raise him on her own. But he had an accident when he was one and he fell off a table and smashed open his head and they had to do brain surgery on him when he was just one year old and it kind of left them sort of like a stroke victim. His left side was limited — his arm and leg he could only use partially. And so he was brought to us when he was two and he's just the most delightful kid and the happiest. You would never know, as tragic as his story is. He's always upbeat and always smiling and always laughing.

And over the last few years, we've started to bring him to America every three months for a very unique therapy that gives him some hope for use of his left arm and his left leg. So it just so happened that on March 1st he came up here, and by March 15th, they basically closed the airports and so we couldn't get him back. And so he has been living with us ever since. And he is just an absolute joy and the joy that he has brought to our home during this lockdown period — the singing and the laughing and the running in the morning, "Oh, Mr. Mitch," just to give you a hug. And you tell him we're going to have ice cream, he jumps out of the chair and he does an ice cream dance. And he's got a dance for every funny thing that there is.

And, of course, he's marveling at America because he hasn't ever spent this much time here to see, even within a household, what goes on. And so it's been struck to me what a joy this young presence of hope is. He doesn't know anything about coronavirus. He doesn't know anything about what's going on, he just knows that we're all home, which is great for him. So I wanted to make a character in Human Touch reflect that kind of uplifting effect that he has had on us. And so Little Moses is basically him incarnated and he has the same effect on the neighborhood; everybody loves him, he never has a bad day, he pretends he's a superhero all the time, which is what Knox does. Knox runs around the house saying, "I am Sonic the Hedgehog," and then he takes off and he just races around.

And so in the book, Little Moses likes The Flash, which is another one Knox likes, "I am The Flash," and he thinks he can run so fast that nobody can see him. So he's very much based on that, and he gives me an outlet to show the joy that children can bring into your life. And you know, from Audible, it's been a wonderful experience with Audible to record this audiobook. And obviously, I don't have time to go recruit actors or anybody to play the parts, so I read the narrative and I read all the parts except Little Moses. And then I bring Knox in because he's a Haitian eight-year-old in the book, so I can't do that accent. And Knox comes in, he sits on my lap and in front of the microphone and I just feed him the lines and he just records the lines and he's great.

He thinks it's a podcast. I don't know where he heard that word, but he says, "Are we going to do the podcast? Are we going to do the podcast?” And I say, "Yes. On Fridays, we record a podcast." "Oh good," and he memorizes the lines. And now he has an interesting addendum to that. He now… somehow, because English is not his first language, when he has to go to the bathroom, when he has to go number two, he says, "I have to go do a podcast." He goes to the bathroom and closes the door and then we hear him singing and talking to himself in there and so he kind of is doing a podcast, but all by himself.

So he's become a star. I mean, he's been on ... Gosh, as we talk about this project, he's been on The Today Show, he's been on the CBS Morning Show, he's been on CNN, he's in People magazine this week. There's a big piece that they did about him and me and a picture of him recording the Audible book. So I'm afraid he's going to call for an agent, I'm not going to be able to talk to him pretty soon. But that's the whole story about little Knox, and we talk to the kids in Haiti all the time and unfortunately, they're on lockdown [at] the orphanage. We've been locked down for the last two months, just prepping for a wave that still hasn't quite hit Haiti yet, but we have to buy two months’ worth of food in advance, two months’ worth of water, fuel, and everything just to be braced for when everything kind of hits the fan there.

So the kids aren't quite sure what's going on or why the teachers can't come in or why they can't go out, but I have to protect them obviously. And so that's a whole other shadow life that I have. I have my household here that I have to protect, but I also have our larger household there.

AW: I guess it's a little too early to say, but how long do you think Knox will get to stay? And how does the lockdown back home impact any of that for him?

MA: Well, it's an interesting question. I imagine America will open up later than Haiti will because Haiti really needs people to come from the States in order to keep its economy going. And so eventually I think that they'll probably make it, "Okay, you can come here." But will America say we can go there and come back into America? I don't know. I've never lived in a time where you couldn't travel somewhere, other than the early days of China or the early days of the Soviet Union or whatever, where Americans basically couldn't get in there. But there was always kind of a way, if you had to. And now, you just can't go anywhere. Certain countries, they won't let you in and we won't let you back. So I don't know. He may graduate high school here, I don't know. So we'll see. He's only eight, so hopefully that won't happen.

AW: I know…. You talked about this very unique narration experience, but do you like narrating in general? You narrate most of your work, which feels very necessary to me, but how have you enjoyed that process?

MA: Well, my reading of the audiobooks began almost out of necessity because when I wrote Tuesdays with Morrie, which was the first book I think that we did an Audible book on, nobody wanted to do it. I mean, it was such a small book and we couldn't afford to go get an actor and nobody was interested in it. And so they basically said, "Well, do you want to read it?" And I said, "Well, I guess I can." And after all, it's written in the first person. And so the parts that are about me and the lines that are about me, I know how to do. And then I knew how to do a pretty good Morrie impersonation. So I figured, okay I'll do that.

I have no doubt that we have saved lives through this project.

And then at the end of my first audiobook, I said to the people—and I'm not even sure who we did it with back then—I said, "Listen, why don't we put on some of Morrie and my conversation at the end, just as like a little surprise?" And they thought it was a great idea. So we've put like 10 minutes of just Morrie and me talking from various Tuesdays. And it turned out to be a very popular audiobook. Maybe because of that, or maybe just because the book was popular, I don't know. But then by the time Five People You Meet in Heaven came around, they said, "Well, you have to read the audiobook. That's what people are used to." I said, "Well, they're not used to it. They didn't have a choice because I couldn't get anybody else to do it." And so that book was inspired by an uncle of mine, Uncle Eddie, who was the Eddie in Five People You Meet in Heaven, and I always knew how Eddie talked because he talked like this and, "Hey buddy boy. How's it going, buddy boy?"

And I said, "Well, this will be a chance for me to sort of channel my uncle and do him." So I did that one. And I thought, "Okay, that'll be the end of it. After this, if there's any other ones, someone else will do it." But then it sort of became a thing that I read them and I think I've read every one except The Time Keeper. The Time Keeper, we've got a British actor named Dan Stevens, I think his name is, I think he was in Downton Abbey, if I'm remembering right.

AW: You're right.

MA: And yeah, because I thought that was an epic book. That was my sort of biggest sweeping historical book. It begins at the beginning of time and ends way in the future. So I thought, "You got to be British to do something like that," and he did a great job, but I've done all the rest of them. And yeah, I like it. I like it a lot. I find that it really helps you realize what you've written. And it's the reason that I also say that Finding Chika to me is the best book I've ever written. And I know that that's sacrilegious to say to some people, because they think Tuesdays with Morrie belongs in its own sort of category. I didn't say it wasn't my favorite book to have done or things like that, but in terms of writing and in terms of crafting a book, I believe that Finding Chika is the best thing I've ever done and maybe will always be, and that's fine with me because she deserves that. I wanted for her, that book to be the best because she doesn't get to be here anymore and I wanted people to know her in the best light.

And when I read it in the audio, I was pleased with it. Whereas, I'm usually, when I read the audiobook, I'm like, "Oh God, now that I'm reading this, I should go back and fix the written one," but it's usually too late, it's already turned in. But I was pleased with the written version and I was pleased with the audio version. It's what I wanted to say. And because it's so close to my own voice, because it's in a conversation with her basically it's written in the second person, so I'm always saying, "Well, Chika. You know Chika. Well, when you did this, Chika. When you did that, Chika." So it's very close to my heart and my voice and that was a good experience for me as well.

AW: Well, you talk about how much Knox feels your inspiration at the moment, but in other times, how do you find inspiration or what inspires you normally?

MA: Oh, that's never a problem. I'm a very hopeful person and I believe in hope and I believe in good things and I find that we live in a world where there's a lot of that is not felt and it's covered up. And so my inspiration to sit down with any idea is to provide something that when people are done reading it, it lifts them up a little bit and it lifts me up a little bit. And that's not hard to do because there's so much beating us down. So my most recent book was a true story, was a nonfiction, Finding Chika, and that was about another little child from Haiti who we were even closer with than we are with Knox because she was a little girl named Chika who we brought up here when she was five years old when it was discovered she had a brain tumor and they told us that she would be dead in four months and we should just take her back to Haiti and just let her die. And I said, "Well, that's not going to happen. We're not like that and she's not like that."

She was born three days before the earthquake and lived through it since she was three days old. So I said, "She was born tough, and if she's going to fight, we're going to fight." And that's what happened. And we ended up spending two years with her as our adopted daughter, and we traveled the world trying to find a cure. And even with something as sad as her passing, which she did when she was seven, I still found inspiration in her and in making a family at our late age. We have 52 orphan kids who we kind of consider our family, but we never had children of our own. And all of a sudden, here we're in our late 50s, and we have this beautiful five-year-old girl suddenly sleeping at the foot of our bed. And all the things that we discovered about becoming parents late in life and the joy that she brought and what's really important when you've done all the career stuff and you've done all the building and establishing and reputations and all these things you think are so important, and then you find that the one thing you really wish you could do, to save a child's life, and you're powerless in that quest. And that's quite a humbling thing. And so there were many lessons to be drawn from it.

So really, Abby, inspiration to me is everywhere and I just look for the vehicle, the framework of the story; should it be a man who dies thinking he doesn't matter and goes to heaven and meets five people who tell him how he mattered? Okay, that's a good way to tell a story about that everybody counts. Should it be a story about how a musician who is so talented that when he plays the guitar, his strings turn blue when he changes people's lives with his talent? Well, that's a good way to tell a story about how each of us is given one particular talent that we have, and if we really realize it, that we can change the world.

So I try to find stories that kind of match the inspirational themes that I am interested in. And when I find one that sort of clicks on, like yeah, that's the right size for that story, or that's the right size for that lesson, then I dive in and pursue it. And as I said a little earlier, there's no shortage of those types of lessons that I have learned that I would love to do books about that at the end you can remember, oh that's the book that kind of teaches you this or that's the book that kind of reinforces this. I just hope I'm granted long enough life to try to get at more of them because I can't usually write every week at a time. I'm pretty slow actually. I usually take about three years to write a book, and so to write one in eight weeks is not me and I'm probably not going to ever be able to do that again.

AW: Well, I’m shifting you to the writing process part of the story. Were you already in the middle of a project? Did you have to backburner something? Or are you trying to parallel write at all?

MA: No, no. Actually, the blessed part of it was that after writing two books in two years, because I had done The Magic Strings of Frankie Presto, so I don't know if that was before. I'd done The Next Person You Meet in Heaven, which was the sequel to The Five People You Met in Heaven, and then Finding Chika one year later. And I never write back to back years. So I had designated 2020 as just a year off and I wasn't going to write any book, I was just going to work on the screenplays and stuff like that, that are always around.

And so fortunately, I didn't have another book to interfere with this. Now, however, I'm as tired as if I wrote a whole book and now before I blink my eyes, it's going to be '21 and I'm going to have to go back to writing again. So it's sort of like I'm getting a summer vacation and then they call you into the office and by the time you look up, it's August, and you say, "Okay, where went the summer?" And so that's kind of it. But it's for a very good cause and I'm so proud of the way that people have responded and so grateful to you at Audible for bringing it to that world.

I'm sure we've gotten many donations from people who have listened to it, who might not otherwise have read it. And we have raised, and I want to encourage people to continue to please help us because it's an ongoing thing, but we have raised over $450,000, all of which we have dedicated and spent ... It doesn't go to any administrative fees or anything like that, it goes right into the city and the projects that we oversee and we have a good network, my charity, SAY Detroit, is a 15-year-old charity, so we have a lot of things in place and people in place and amongst the things we've done, including feeding 2,000 seniors three meals a day, making sure they don't have to go out, and taking care of kids at our academic center, 100 of them, and first responders and PPEs and temperature gauges and masks and many other things like that, but what we really are proudest of is we opened the second testing center in Detroit.

There was only one testing center in all of Detroit, it was kind of in the northern part of the city, kind of hard to get to. And you had to drive through, it was only from mobile drive-throughs. Well there's a lot of people in our city who don't have cars, especially in Detroit. And so we opened the first walk-up testing center where you can drive in or you can walk in. And we've administered thousands of tests already to people and sadly, our numbers come back between 30 and 40% as COVID-positive. So you see how big a problem it is in Detroit. And so we are running that testing center directly with the dollars that come in from Human Touch. I mean, that's the fuel that keeps that engine going.

So I want to encourage people to continue to ... Our average donation is about $20, and with the $20 average donation, we managed to raise all that much money and that's because there are people around the world who are kind and believe in paying something forward. And so I want to encourage them to keep doing it, because we're going to keep needing to test well into the fall. And this isn't going to stop. And so the more people continue to read and fund it, the more we can pay for it.

AW: I know that you're doing this as you go along and for good reasoning, as you mentioned, the developing story of it all in the world, but do you have a sense of how you want to end it, how it could end, should the realities of life not change?

MA: Well, I'm writing the ending, the last chapter now, which won't come out until Friday the 29th of May, will be the eighth and final chapter. So if we had this conversation last week, I would've said, "I still don't know how it ends," because I only run one week ahead at a time. But now that I'm working on the ending ... And it ends a little further in the future than where we are now. It started a little before where we were because I started with the very first week that anyone even heard about the virus, whereas in truth, when it came out, we were already into the whole coronavirus pandemic, but now I'm ending it months after it actually ends with some predictions as to what happened. And it's got an uplifting ending, but not without some costs and not without some peril. There are characters who don't make it, and that has to be realistic. You can't create a story that's supposed to be ... Even if you want to make it inspirational and hopeful, you can't have everybody survive or it's not being reflective of what's really going on.

And so there's some heartbreak in the last chapter as well as some inspirational things. And of course, Little Moses is at the center of the whole thing and you want to find out what happens to him. So yeah, it'll be uplifting and I don't know how realistic it will be, but it's a novel so I'm not trying to write the medical journals of the future, but I think that the way it ends is a derivative possibility of it being the actual way that this ends, at least I hope.

AW: Okay. Yeah, it's got the very ripped from the headlines feel and you don't shy away from those moments of ugliness and the fear that especially dominated the beginning and the unrolling, unfurling of the story. But you also, you have these moments of kindness and exploration and you talk about the fact that you know how to move forward in tough times. How do you hope this gives people an advice, struggling to do the same, to move forward through fear and concern and just uncertainty?

MA: Well, I guess for me, I'm very confident that we can do that. And part of that comes from just sort of... I guess, a personality trait that tends to veer towards hope rather than despair. But also, I've been blessed in my life to see a lot of things and I have seen worse. I was there in Haiti after that earthquake and had to rebuild the place, and that was a lot more than just staying home and hoping that the stimulus check or the unemployment covers your immediate bills, that was total wipe out destruction. That was "My family is gone, there's nobody left. My house is destroyed, there's nobody to take care of me. I can't eat, I'm starving. There's no water, there's nothing clean." And when you see that there are parts of the world that have endured that, and I've watched that in Haiti for 10 years and seen that they came out of it, then you believe that we can come out of this and we can.

And this is going to kill more of us than it ever should and never should have, but it's not going to kill all of us or even any large percentage of us and it's not going to destroy us and it's not like... There are steps that you can take. Whereas, if you want to stay inside and protect yourself, keep a mask on, take a financial hit, but be safe, you'll be safe.

What about all the people in the world who say, "I just want to hide in my home," and they come and burn their home down because they're in a war? "I'll stay here. I won't go out." Boom, a grenade explodes nearby or a bomb. This happens all over the world. So I try to take a relative view of this. This is not the worst thing to ever happen to anyone. And we as Americans need to suck up a little bit and say we're blessed and we need to know that we're blessed. But we also need to know that when something hits us, just because from going from a blessed position to having to suffer a little bit really feels bad, it isn't the worst thing in the world. And we don't look good by acting like, "Oh my God, how can we be so inconvenienced to go two months without having our nails done? Enough is enough." It makes us look foolish on a world stage where people are all suffering the same thing.

When this thing hits Haiti, not to belabor Haiti, but I know Haiti, when this thing hits Haiti, there's no choice for the people there. They can't hide inside. They have to come out every day to get food. There's no refrigerators, no freezers, there's no electricity that runs straight through the night. We get electricity sometimes two or three hours a day and that's it. Everything else, we work off a generator, but most other people don't have that kind of thing. So where are those people going to go? Where are they going to go in a country that has 30 ICU beds in the whole country? Where are they going to go? What hospital are they going to run to?

So we have to count our blessings. And I do. There has to be a country where you have to get this. We're fortunate to be in America where we have a government that actually votes, "Okay, we'll send you money, extra money to tide you over." And many of us say that's not enough. Try being in like virtually 98% of the other countries that don't give their citizens anything. So I just say that if we look at it as, "All right, this is a test, we'll be stronger as a result of it. How can we help one another during it?" Which is what I've tried to do with this book, we'll be distracted from the inconveniences of it. But I also know that it's not the worst thing that's ever going to hit us, and because of that, we can come through it and I just try to spread that message wherever I can.

AW: I love that this is the continuing theme of your work, of drilling it down to the basic human need, that connection and to show up for each other. And that's already coming through.

MA: Well, I hope so.

I've had a number of people who've said to me, "I love this idea. I'm waiting until it's done because I like to binge. I like to binge watch, I want to binge listen. I'm going to listen to eight straight chapters in a row. I don't want to listen to one through six and then not be able to hear the last two and have to wait for weeks." That's fine too. It's going to be there for a while.

Just all I ask is that when you're done, please consider making a donation if you've enjoyed it in any way, if you can spare anything. There are a lot of people who unfortunately are dealing so much with just surviving this thing. They don't have time to read a book. They don't have time to listen to a book. They're trying to keep their loved ones alive, or they're on a ventilator themselves, they're trying to fight through coughing and burning lungs and fevers and things like that. So I always think of them and say, "If we have enough time to read a book or listen to a book and we have a little bit of means, then we have enough time to help somebody else who can't."

AW: I can't think of a more brilliant way to end this interview. That's the perfect note. Mitch, thank you so much for working on this project, for coming up with it and for sharing it and speaking with us about it today.

MA: Oh, it's been my pleasure, Abby. Thank you. And everybody at Audible for being so quick to get on board with this. It wasn't an easy thing for Audible to do. It wouldn't have been easy for anybody. It's not a normal model to put something up for free and there's not a lot from a profit point of view in it for Audible to do. And to be blunt, I was kind of pleasantly surprised that Audible agreed to do it because I kept thinking, "Well, business is a business and everyone wants to make a profit and we're not offering profit here," but you did and you came through and you showed that's not always the only motivation for things, and as a result, you're responsible for saving lives.

I have no doubt that we have saved lives through this project. When we're talking about thousands of people who've been tested, who then have the information and know to separate from their families or get to a hospital and get cured, there's no question that this project has indirectly saved lives and therefore Audible has saved lives as well. So my hat's off to all of you there.

AW: Thank you. We take our people principle of activating caring quite truly, deeply, literally all around. So we're really happy to have done this and be a part of this with you.