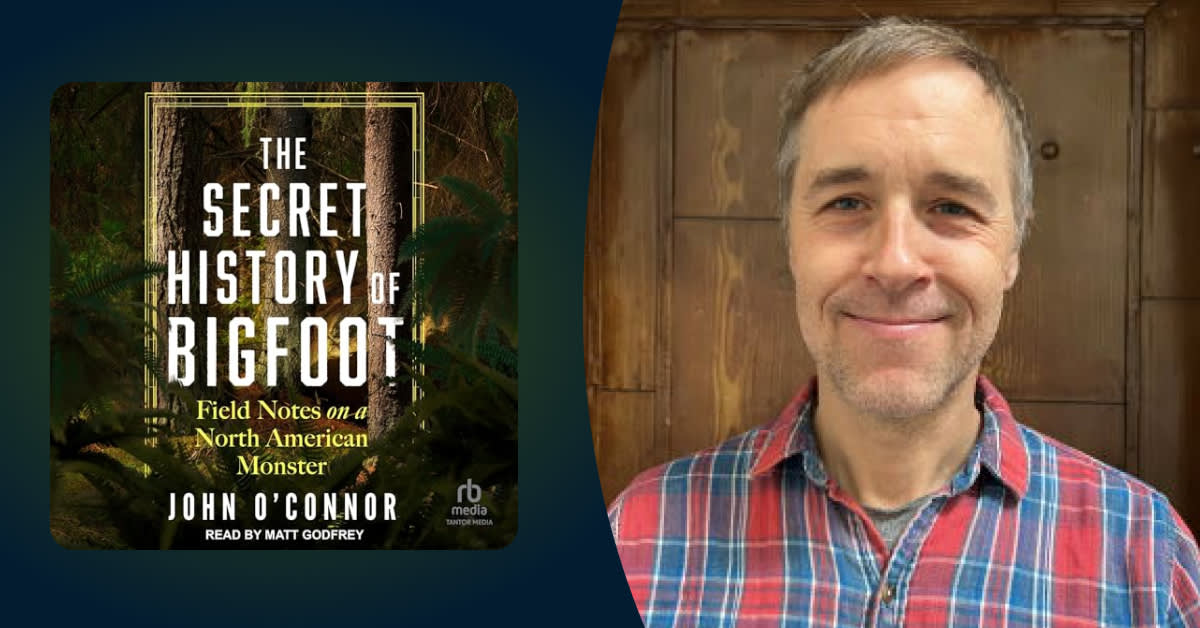

Technically speaking, I don't believe in cryptids—but that's never stopped me from loving them! Give me a close-encounter memoir or paranormal podcast and I'm in for the ride, the wilder the better. And no mysterious creature looms larger than Bigfoot, so when I spotted a new survey of Sasquatch lumbering in the realm of nonfiction, I had to ask the author all about it. Here, John O'Connor gives us the big, hairy scoop on A Secret History of Bigfoot: Field Notes on a North American Monster.

Kat Johnson: Let’s start with the big Bigfoot question: Are you a believer? How did working on this project influence your thinking in any direction?

John O’Connor: I’m a little reluctant to answer this directly because it’s a potential spoiler. I want listeners to discover the answer for themselves. But I don’t think it’ll take them long to figure it out. My beliefs become apparent pretty early on in the book. I hope it goes without saying that I think we should be guided by reason and rationality, and that Bigfoot doesn’t hold up well here. Challenges to reason are everywhere in public life today—unreason being one of the biggest challenges facing us—and I worry a lot in the book that Bigfoot isn’t doing us many favors in this respect. Of course, we all harbor strange beliefs, whether we realize it or not. In a sense, we’re hardwired that way. But we have to try to stay anchored to logic and verifiable fact.

At the same time, I don’t think we want to lose all contact with a more enchanted view of the world. Science only delivers us so much. People seem to need more than what reason allows, including very smart people. We want to be awed and mystified as much as, and possibly even more than, we want to see clearly. And that’s a central tension in the book, balancing these two competing sentiments: science and reason versus an almost spiritual sense of what’s possible. It was the hardest thing to grapple with because as much as I wanted to entertain possibilities and be open-minded, and as much as I wanted to be fair to my subjects and their beliefs, I found myself reflexively rolling my eyes a lot. And I think that kind of attitude can be dangerous too sometimes.

Say you’re at a party talking to a skeptical type, someone suspicious of anything not verified by science. How do you explain The Secret History of Bigfoot to them?

Well, first I’d be sympathetic, because that person is me. I’m a skeptic. As I ask in the book, how is it remotely possible that an 800-pound mammal can survive undetected in the American wilds, or for that matter in the American exurbs, as some Bigfooters contend? There’s no real evidence to speak of—no good videos or photographs at a time when virtually every person on Earth has a high-quality camera in their pocket. There’s no bones or Bigfoot remains. What’s up with that?

“We have an inbuilt, desperate need to believe in the unbelievable.”

On the face of it, it’s completely batshit and absurd. It defies all logic and may even be an insult to our intelligence. So first I’d say, I totally get it! You should be skeptical. But I’d also follow that up by saying, "Hold on just a second. Why are you so certain? And what does your certainty reveal about you and your view of the world and the people in it?" Certitude—and the knee-jerk dismissal of people whose beliefs differ from your own—being another major challenge in American public life.

The Sasquatch world is full of colorful human characters. Who are some of the standouts that listeners will meet in the audiobook?

In order of appearance, Jonathan Wilk of Team Squatchachusetts, Lyndsey and Charlie Raymond of the Kentucky Bigfoot Research Organization, and Rowdy Kelley, Robert Leiterman, and Daniel Perez of the Bluff Creek Project. And also James “Bobo” Fay of Finding Bigfoot fame, whose cameo late in the book may surprise folks who think they know him based on the Discovery Channel show.

Can you share some of your favorite influences or references, whether literary or cinematic, that fans of The Secret History of Bigfoot should check out?

Kurt Andersen’s remarkable book, Fantasyland: How America Went Haywire: A 500-Year History (2017) was an early touchstone for me. It traces a depressingly long line of religious and cultural delusion in the American past and present, beginning with the Puritans in New England and ending with Donald Trump in the White House. I read it during the pandemic and the timing was fortuitous. Andersen doesn’t mention Bigfoot, but I’d been thinking a lot about it then and began to wonder where Bigfoot landed on the continuum of magical thinking that Andersen unravels.

Lisa Feldman Barrett’s How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain (2017) is a perfect companion to Fantasyland. While Andersen deals with the cultural-social-historical side of things, Barrett, a neuroscientist, tackles the psychology behind our cognitive biases and the considerable downsides of constructed memory and a predictive brain—in short, why we tend to see what we want to see. Her decades of research confirm what many of us might have suspected—that we’re extremely attached to the way we think things are and refuse to relinquish those attachments even at knife point. I mean that almost literally: Some of us would rather die than change our minds.

With podcasts I’m incredibly late to the game. I only recently began listening to them. But a favorite is Very Bad Wizards with psychologist David Pizarro and philosopher Tamler Sommers. Again, they never mention Bigfoot as far as I can tell, but they circle many of the themes—neuroscience, pop culture, politics, and moral philosophy—that I do in the book. Plus, they’re funny guys. Last, I can’t stress enough how haunted I was in my late-adolescence by John McTiernan’s masterpiece, Predator (1987), a film that also mines many of the themes that occupied me during the writing of this book. Incidentally, I’ve had a lifelong crush on the actress Elpidia Carrillo, who in Predator steals every scene she’s in, which is fortunately quite a lot.

“Bigfoot is an existential bargain of sorts, a bid to wrest something more satisfying and less depressing from life, something more surprising and perhaps a little more untoward.”

Rounding out with the other big question: How do you think the Big Guy maintains such a passionate fanbase around the world—what makes him the king of all cryptids and what’s behind the enduring fascination?

Because he’s us, basically. And because we have an inbuilt, desperate need to believe in the unbelievable. There are folks who contend that the modern Bigfoot owes its existence entirely to hoaxers—the oddballs who leave fake Bigfoot “footprints” in the woods and such—and to the internet. I buy that to some extent. But I also think it has a lot to do with a very human desire to believe in the preposterous, and with confirmation biases that allow us to continue believing what we already believe despite damning contrary evidence.

These are cross-cultural, transhistorical phenomena. In The Swerve: How the World Became Modern (2011), Stephen Greenblatt says that for most people the notion of a finite material world has always been intolerable. The idea that we only get one “at-bat” in life, one achingly brief moment on this planet, which is gone in an instant—a life that for a significant portion of humanity, through most of history, has been largely defined by suffering—before getting dumped into a hole in the ground; many of us just can’t swallow it. Religion, Greenblatt says, is an attempt to strike a better deal for ourselves with God. And of course to help us suffer less in the here-and-now.

By the same token, Bigfoot is an existential bargain of sorts, a bid to wrest something more satisfying and less depressing from life, something more surprising and perhaps a little more untoward from our soul-crushing, humdrum existence. And it’s also a middle-finger to the rationalist’s contention that the quantifiable, visible world is all there is. For so many of us, believing in the opposite—that as The X-Files tagline put it, “The truth is out there” and we’re in hot pursuit—is irresistible. There are potentially bad outcomes to this way of thinking—Pizzagate comes immediately to mind—but with Bigfoot I’d argue that’s typically not the case. He (or she) is mostly an innocuous reminder that we don't want or seek rational explanations for a lot of things. In fact, we prefer that they remain mysterious.