Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

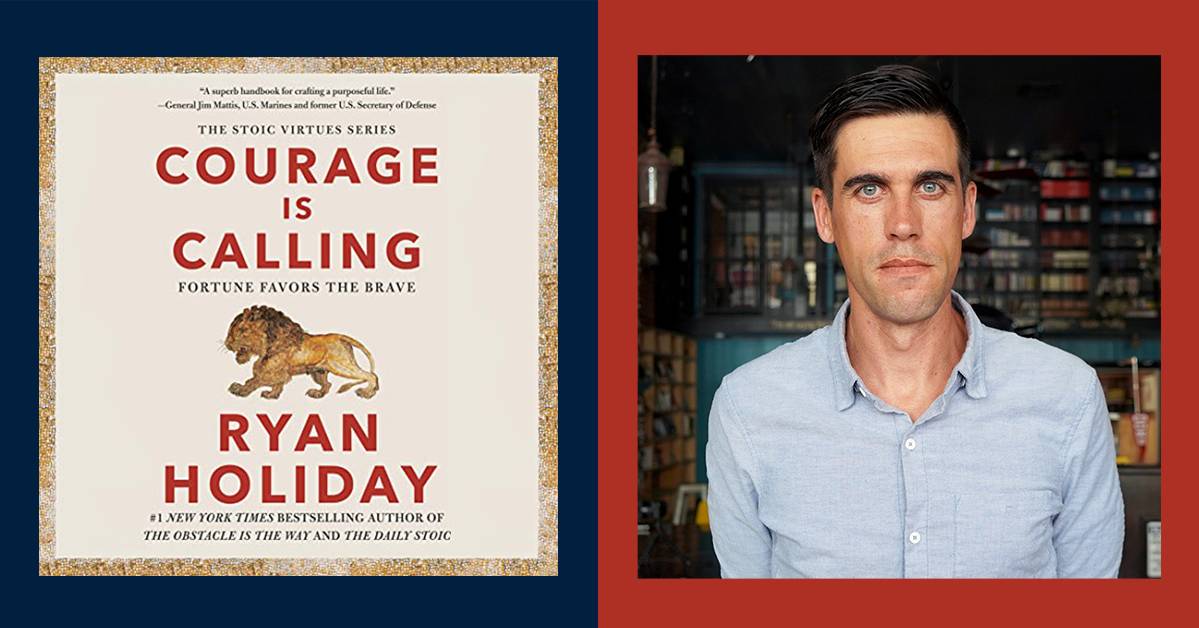

Kat Johnson: Hi, I'm Audible Editor Kat Johnson, and I'm here with Ryan Holiday, who is the author and narrator of the best-selling books Stillness Is the Key, The Obstacle Is The Way, and Conspiracy: A True Story of Power, Sex, and a Billionaire's Secret Plot to Destroy a Media Empire, among others. His brand-new book, Courage Is Calling, is the first in a four-book series on the Stoic virtues. It is such a thrill to talk to you today, Ryan. Welcome.

Ryan Holiday: Thanks for having me.

KJ: Thank you so much for being here, and congratulations on this book, because as we're recording the interview, it released today. So that's a big deal.

RH: Yeah, launch days are always weird, so it's nice to have something to do. I'm not just pacing around checking my Amazon rank.

KJ: Yeah, don't do that. I'm actually a huge fan of your work and a subscriber to your reading list newsletter, and recently you said, "12 years ago when I started this newsletter, I hoped that one day I'd be able to tell you guys that I had written a book." And now here it is, and this is your 12th book that you're publishing today. That's incredible. And I want to know, how personal was this book for you to write? Because as a listener, that's how it came across to me.

RH: I've had this happen now in a couple of books, where you have this idea of what you want to write and you start it and it takes so long for a book to get going, because first you have to sell it. Then there's the contractual period, then there's the research, and then you start. So all of that happened in mid-2019. I had no conception that I would have to sit down and get serious about writing it in the middle of a global pandemic when the world had shut down.

I went through that on my book Ego Is the Enemy too. I was writing about ego and then I watched American Apparel implode largely due to ego. So it kind of works out very nicely in that exactly what you need therapy about is what you're thinking about and exploring, and, at least in the style of books I do, learning from some of the bravest, smartest, wisest people who ever lived.

"I think courage has always been rare. But weirdly as the world has become less dangerous, we're somehow more afraid."

It was really wonderful and personal as the world was imploding to be reading about people who had gone through pandemics or plagues or other much more difficult things and be like, oh, okay, people get through these things. There's an example to follow, and I took a lot of solace in that.

KJ: Speaking of needing therapy, at times when I was listening to this I almost felt attacked by how much our lives are guided by fear. Do you see this as an urgent problem?

RH: I think courage has always been rare. But weirdly as the world has become less dangerous, we're somehow more afraid. I talked a lot about political dissent in the book. If you defy the Roman emperor, you could be exiled, you could be executed, your home and estate could be confiscated. And then to watch this slow-moving political crisis that we've been in for the last several years, where the stakes are so much lower, right?

I don't mean the stakes of what you're speaking up about are low. I did feel like it was urgent, and I should say, whenever it feels like the reader is being attacked, the primary recipient of that message is myself.

KJ: Right. And I think that humility comes through. I do want to ask a little about the trajectory of your career, because as you mentioned, you started your career in public relations, including for American Apparel, and your first book was an exposé of media manipulation called Trust Me, I'm Lying. What do you think is the through-line between your books on marketing and media and your later writing about stoicism, including this new book on courage?

RH: Well, it's kind of weird, because I was actually writing about ancient philosophy first, and then Trust Me, I'm Lying came out and people were like, "What is this? I thought you write about ancient philosophy." And then that book became successful. And then when I published my first philosophy book, people were like, "I thought you write about marketing." So I've kind of had this weird back and forth [on] two different tracks of my writing career. I'm always interested in saying what I think needs to be said, whether it's something I'm studying historically or something I've experienced personally. I wish that my first book had either been proven wrong or become irrelevant as time passed. The fact that the ideas in that book remain relevant and the book still sells, to me, it's obviously success as an author, but sort of an indictment of society.

"Whenever it feels like the reader is being attacked, the primary recipient of that message is myself."

As I was trying to describe in 2011, the way that fake news works, the way that bad actors can manipulate media, the way we can be riled up and turned against each other should not be possible. We need to make changes to stop this from happening. It really feels like the absolute worst people in our society have figured out how that system works, and they use it more effectively than people who have positive or helpful or unifying messages.

KJ: Right. I agree with all of that. Given how rare courage is, do you feel optimistic about the future?

RH: I feel like the ultimate act of courage in a broken, dysfunctional depressing world is to hold on to some form of hope, to not give up on people.

It's both a hope and a belief in one's ability to make a better future that makes that possible. There's a kind of cowardice in nihilism or hopelessness. So I have been trying to not focus on the positive, but try to zoom out and think about these things historically. And that does give me some bit of perspective. I mean, if I had to choose all of the times to be alive in human history, there's no question you would choose right now, right? Would you rather be alive in COVID or the Spanish flu?

So, I do find hope when I zoom out, but when you stare at things too close and you think about it too much, your courage can falter certainly.

KJ: How do you balance the stoic idea that doing hard things and not taking the easy road are the key to a virtuous life with the reality that so many people are suffering from massive inequality of wealth and resources and that these struggles make it harder, not easier, for them to succeed?

RH: So you take an exercise, like Seneca says we should practice poverty on a regular basis. He means, like, eat bad food, sleep on a hard mattress. He basically means try to get comfortable being uncomfortable on a fairly regular basis. Now, there is of course, a certain amount of privilege in this, because for someone who this is their daily life does not need to practice it; they're intimately familiar with it.

"I feel like the ultimate act of courage in a broken, dysfunctional depressing world is to hold on to some form of hope, to not give up on people."

I don't think he's being offensive though. I think his point is, particularly if you have been successful, you are privileged. You're going through life and things are great. You have a good job. You have a nice house. You came from a stable home. You haven't experienced significant trauma. It's very easy to become scared of something happening to those things.

So you're afraid of taking risks. You walk through the world rather fragile or paranoid. You have this kind of existential dread or anxiety that the wheels are going to come off, right? I think we saw this during the pandemic. Things have been happening like this at all times, but suddenly not being able to travel, suddenly not having childcare, suddenly having to take a hit watching some of your savings evaporate, whatever it is. This is normal existence for lots of people.

For people who've gotten very used to a certain baseline, they had trouble adjusting, or even just take the powerlessness of the last 18 months that so much of it's been out of our control for people who are very used to doing whatever they want.

I think what Seneca and with the Stoics are talking about is putting yourself in a position where you're not afraid to take a step back. You're not afraid of uncertainty. You're not afraid of change. You're not afraid to commit to something that you believe in, whether it's a cause or starting a business or taking a career risk. Being like, oh, I'm okay living in a one-bedroom apartment, makes it easier to say I'm gonna walk away from my corporate job to pursue this cool opportunity, because the worst-case scenario is actually not as scary as perhaps it would be to a more spoiled, comfortable person.

KJ: That makes a lot of sense. One of the great pleasures of all of your work is just uncovering all these great historical anecdotes that you fill in to illustrate your points. In this particular book, I really loved hearing about Florence Nightingale and what a big leap she took in answering her own call to courage. How did you land on Florence Nightingale as one of the key figures in the book?

RH: Well, I wouldn't be able to do it without Amazon, of course, because the book that I read about Florence Nightingale is an old library book from 1951. So they're not selling this at bookstores anymore. I don't know how I got recommended to it. I think I chanced upon it randomly. I tend to read a lot of old books.

I used these note cards—this is audio, so people won't be able to see that—but I use note cards. So there's a four-book series. At the top it says "courage," "temperance," "justice," "wisdom." And then as I'm reading, I'm taking notes or ideas from the books that I like. And then those note cards get accumulated and become the book.

What I'm doing is I'm reading very widely. Then I'm breaking down and organizing that material. Then once I have huge, massive material, then I am going through and trying to find themes or ideas. I just chanced upon a book about Florence Nightingale. I read it, and I really liked it. I had enough note cards that they really slotted in nicely to the fear chapter.

I'm writing about Queen Elizabeth right now for the next book in this series; she's the main character in part two. I've read about 2,000 pages about her, which probably gets whittled down to like 100 or so note cards, which then might translate to 4,000 to 5,000 words of text.

KJ: Wow. That's amazing.

RH: That's the only reason that I don't listen to a lot of audiobooks is that it doesn't work as well for that system. I need to be able to go, oh, this story on page 52. I need to be able to readily refer back to the material very easily. The hardest part in the process for me is just finding the source material.

KJ: Wow. So you said you're not so much of an audiobook listener for research, but you are quite a prolific narrator. You've racked up some credits there.

RH: I've done all my books, actually.

KJ: You've done all your books. How has that been for you?

RH: I remember somebody I knew who was an author was like, "You should read your own audiobooks. They pay you for it." And I was like, "Oh, okay. That sounds fun." And so I did it and it took like six days in a studio. It was exhausting. And then the publisher sent me like a check for like a thousand dollars. And I was like, that probably was like minimum wage that I just agreed to do this for.

But then the next book I didn't do the audio one for that one because I didn't love the experience the first time. And I got so many emails from people. They were like, "Who is this person? We liked the first one because you did it." So basically that sewed it up for me and now I've done all of them since.

And then for Lives of the Stoics and this book because of the pandemic, I couldn't go to a studio. So I had to record them here in my office without the AC in the middle of the Texas summer. So that was a fun experience as well.

KJ: I put you in the group of nonfiction writers whose work is just more special to experience in their own voice. There's people like Michael Pollan, Brené Brown, Ta-Nehisi Coates. It's great to hear you saying it how you intended to.

RH: It's really fun. One, because you would never read your book out loud ordinarily, right? I actually consider it a really important part of the editing process. So I try to record it. The publisher was like, "Okay, it's gonna come out in September. You probably don't need to record it until late August." And I was like, "No, I need to record it as early as possible, because I want to be able to make changes based on how it rolls off the tongue." That's actually become a part of the process for me.

I usually will emerge feeling better about the book but worse about myself, because I don't know how to pronounce words. I had to look up 50 words on YouTube that I put in my own book that apparently I'm not sure how to pronounce, or then they send you the pickups and they're like, okay, here's all the things you have to rerecord. And then it's like, oh, I've been mispronouncing this word the entirety of my life. That's very embarrassing. And nobody said anything about it until right now. I'm like, seriously, you have to spell this out.

So again, it does not leave me feeling great about myself when I'm finished.

KJ: Well, I appreciate it. It's nice to hear it in your own voice. One of my favorite parts of the book was at the end, when you bring up your time at American Apparel and you spoke to how courage tied into what happened there, and you said you didn't want to include it and you almost didn't. So what persuaded you to change your mind? And why did you put that there?

RH: The main reason, for people who haven't heard it yet, I talk about sort of being asked to do something unethical at work. I didn't do it, but I didn't stop it from happening either. It's not an incriminating thing, but I look back at myself and feel that I fell short and I'm not proud of it.

So the decision to basically unsolicitedly confess and expose a moment of failure, I had some hesitation about. But it's funny, I have a chapter earlier in the book, I'm talking about Theodore Roosevelt and he's thinking about asking Booker T. Washington to have dinner at the White House. The first African American ever to be invited. Obviously many had had dinner inside the White House as servants and slaves and such, but no one had been ever invited as a guest of honor.

Roosevelt being an astute politician knows instinctively this is probably going to be controversial. It may even cost him the election. He does a quick cost-benefit analysis, but then he stops himself and he goes, because I hesitated, I hurried to do it, meaning that because he was worried, he thought for a second about the political ramifications and considered not doing the right thing for that reason was exactly why he ended up doing it.

You should always say what you're afraid to say, because chances are other people aren't saying it and chances are it's probably honest and vulnerable and real compared to the things you feel great about saying, which usually feel great because they make you look good.

KJ: You hear that advice, go in the direction of your discomfort. Do you think this is the last word on your time at American Apparel?

RH: I don't know. It is kind of weird that there hasn't been a great book written about it. Some people were working on a documentary that I was hoping might happen. I talked a little bit about it in my book Ego Is the Enemy. I talk a little bit about it in my book Stillness Is the Key. This is probably the most direct that I've been able to be.

I go back and forth between really wanting to talk more about it and then not wanting to dwell on it. It remains obviously a very formative period of my life in a bunch cautionary lessons that I've tried to integrate, if not directly in my books, certainly informed the characters. I try to always take my experiences and analyze less controversial or less current figures through the lens of those experiences.

KJ: Got it. I think with more distance we'll see more interest in it.

I want to talk a little bit about the next three books, and you kind of rattled them off. So that's courage, wisdom, temperance, and justice.

RH: The virtues are all very related to each other and almost impossible to separate. You need courage, but courageously pursuing the wrong thing is not great. But also let's say you're an author. You love ideas, but you're afraid of ideas that challenge you, that make you uncomfortable. Well, that's not gonna work either. And so you need courage to pursue things with wisdom. You also need self-discipline or moderation to know what the right amount of things are to pursue them correctly so they all connect with each other.

KJ: Right. And then thinking about vices, it's hard for me to get jazzed about temperance. It's really hard to make moderation interesting.

RH: That is the challenge for me that I've been struggling with the last several months. We associate temperance with abstinence. Actually, temperance means the right amount. It means moderation, but I'm really pivoting and making that book much more about self-discipline than about moderation.

Often, I'll start with a topic that's based in the literature. But the exact reaction you had is why temperance is an uncommon virtue; it's that people don't understand it. They have an instinctually negative reaction to it. What's a better way to think about this, to talk about it? What's a better handle to grab it with? The book is going to be much more about self-discipline, so self-control, dedication, commitment, work ethic, checking ambition or greed or excess. It's going to be more about that than just don't do too much, which would be boring.

KJ: I'll look forward to that. So why did you start with courage, and is there an order that you know that these are coming out?

RH: The Stoics tend to list them as courage, temperance, justice, wisdom. I liked the idea of wisdom being the last one. Justice struck me as being politically charged and not the right one to start the series with.

And then courage, I felt, was not only the most exciting and the most interesting, is almost always put first, because I feel like you can't have any of the virtues without courage. To be temperate in a time of excess requires courage, the pursuit of justice demands bravery, and then, of course, nothing is scarier than truth and the pursuit of knowledge.

KJ: Right. That makes sense. So you've been writing about the Stoics for close to a decade, probably longer than a decade, given your interest in it. What is it about stoicism that continues to inspire and engage you after all this time?

RH: I think it's the people. I've been writing about the ideas in stoicism for a very long time, but what keeps me perpetually fascinated, and I talked about this a lot in Lives of the Stoics, is that these weren't academic philosophers, but actual people. It was not until this year or last year that it fully hit me that Marcus Aurelius was alive during a plague, and that he's speaking about it, not just figuratively, but also literally.

And the idea that philosophy was one part of who they were as professionals. I mean, Seneca is Rome's most powerful political broker, its most famous philosopher and its most famous playwright at the same time. I just am fascinated by them as human beings because I think, unlike a lot of philosophy, which is often abstract or theoretical or impractical, the Stoics were like, no, no, no, I'm talking about this as the emperor of Rome. I'm talking about this as an author. I'm talking about this as a human being with kids. I just love that the Stoics were human beings, and I think that's what makes it impossible to get tired of.

KJ: Yeah. And what do you think they would think about the situation that we're in today?

RH: I don't think it would surprise or shock them. I think they'd be quite at home with it—an empire in decline, a plague, political violence, ignorance, ambition, tyrants, this is par for the course. Even cancel culture. They had that. I love the idea that the more things change, the more they stay the same.

KJ: Right. And it's all in the name. It's like they'd accept it stoically.

RH: Yes. I hope so.

KJ: Can you share anything with us about what you're working on next? Because I know you're probably doing so much even besides the next three books in the series.

RH: I woke up this morning and I was working on the self-discipline book, the second book in the series. I just did a book with Chris Bosh called Letters to a Young Athlete that I think is really good, and I believe he read the audiobook. So I think that's a really interesting one. And then I'm doing a book for Portfolio called the Daily Dad, which is a daily reader of parenting advice that I have to start thinking about here really soon because I need to write it.

KJ: That all sounds fascinating. Congratulations again. Courage Is Calling, written and narrated by Ryan Holiday, is available on Audible now. Thanks, Ryan.

RH: Thank you.