Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

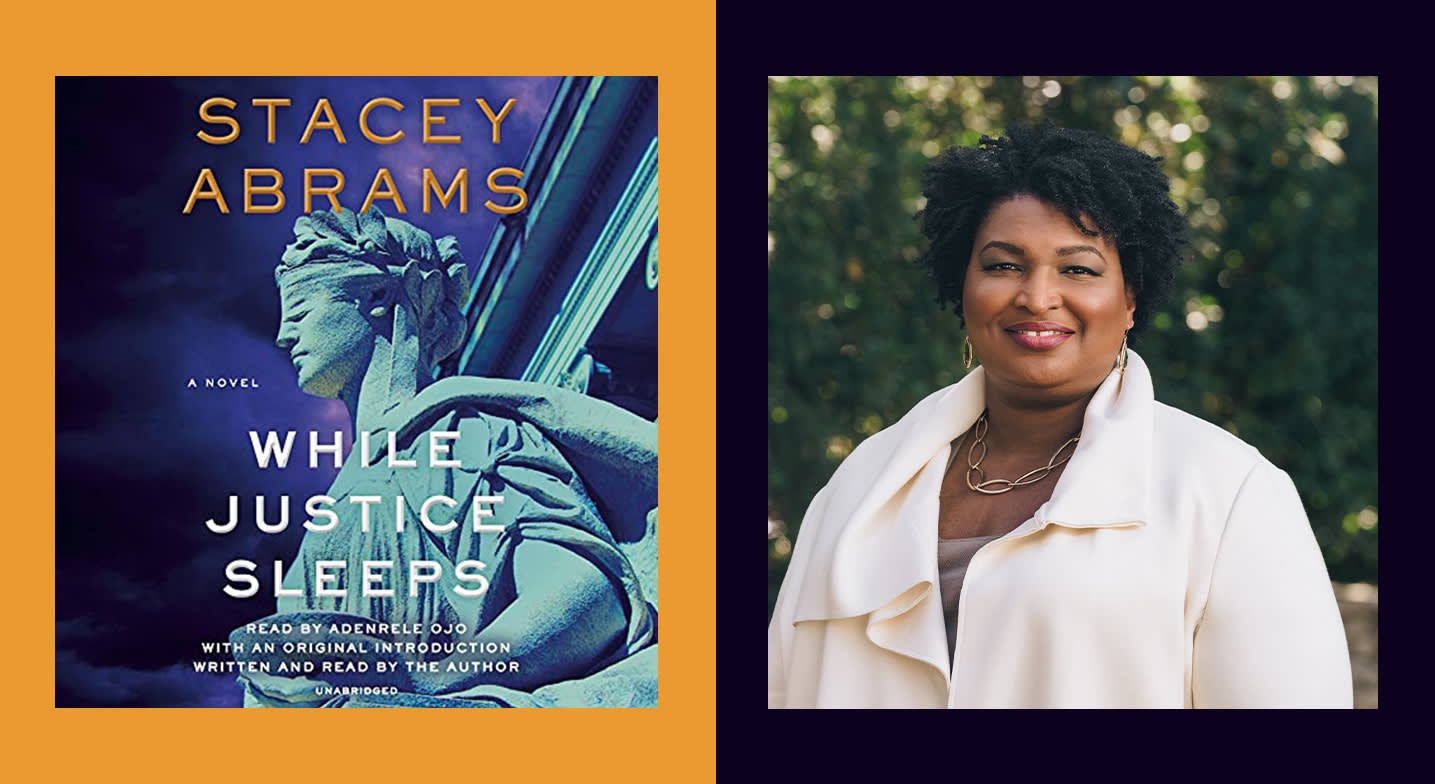

Margaret Hargrove: I'm Audible Editor Margaret Hargrove, and I'm so honored to be here today with Stacey Abrams. Stacey is a former Georgia House representative, a voting rights activist, and the author of a new thriller, While Justice Sleeps. Welcome, Stacey, and thank you for joining me today.

Stacey Abrams: Thank you for having me.

MH: For our listeners who don't know, which is very hard to imagine, Stacey, you are one of the hardest-working and most inspiring people in America. You ran for governor of Georgia in 2018, you've launched multiple organizations devoted to voting rights, and you're a best-selling author. While Justice Sleeps is new territory for you as your first legal thriller.

I read that you wrote this book nearly a decade ago and publishers passed on it twice. What kept you pushing to get this book published and get this story out there?

SA: The first book I wrote was Rules of Engagement. It was my romantic suspense novel. It actually started out as an espionage novel. I wanted to write about this woman who was a chemical physicist who solved this complicated web of lies, and I was told that publishers did not publish espionage novels by or about women and there were no Black spies in the mainstream.

"The most dangerous part of telling a good story is getting it almost right."

And so my response was, okay, fine. I killed all the people I planned to kill, I just made my spies fall in love, and published it as romance. By the time I wrote While Justice Sleeps, I had learned that part of the obligation of being a writer is getting the words on a page, part of the business of being a writer is finding the right place and the right time to push your book out there.

When I couldn't get it sold the first time, I set it aside. I was a little distracted, had a few other things on my plate. I was minority leader and I'd started a small business, some elections and stuff. But when I came back to it the second time, I cut a number of chapters, I tried to streamline the language, and when it didn't work a second time, for me it was more a question of, is this the right time? Because if I truly believed in my work as a writer, and I did, then the question was as a business question, as a business issue, when could it make its way into the field?

I actually forgot about it for a while. Last time I tried to push it out there was 2015, and I want to be clear, I was sending it to agents who were basically saying, "This is not gonna make it into the publishing world." And so when the third time struck, I was actually in Hollywood, selling my other books. There were a couple producers who were interested in my romantic suspense novels and so I was pitching those and someone asked, "Well, do you have anything else you've written?" And I was like, "Yeah."

Like most writers, I was in medias res in a few other projects and I mentioned that I had this other book, and they were intrigued. And I missed it the first time, the first time someone showed interest. I was so used to it not being something I could sell, I didn't pay that much attention, and one of my staff members who was with me nudged me at the next meeting to talk about it. And then when they realized it wasn't just an idea, it was actual book, it renewed in me this notion that I've always had, which is that the writing is for me and the selling of this work is an opportunity, but not an obligation, and this was an opportunity to see if someone would be obligated to take it.

MH: Well, third time was definitely the charm, and we're so happy that it's out. Was there a particular moment from your career that inspired the story of While Justice Sleeps?

SA: No. The idea came from an extraordinary attorney I had the privilege of working with when I first started out. She was one of the only Black woman partners in major firms in Georgia and she was one of my strongest supporters. We stayed in touch after I left the law firm, after I'd gone into entrepreneurship, was in the legislature, and she was telling me this story, because she knew of my writing and she thought it was a fascinating idea, and it just caught me and I couldn't let it go.

My experience as a legislator, my experience as a young lawyer, my deep love of politics, those all informed the story. But truly the story began when she gave me the nudge that became Howard Wynn, one of the main characters.

MH: What's so interesting to me is that even though you did write this book nearly a decade ago, there's a prescient feel to it, especially given everything that's been going on in this country for the last couple of years. So in While Justice Sleeps, I'll just give a little sneak peek for our listeners, Avery Keene is a law clerk who unexpectedly finds herself the legal guardian for a Supreme Court justice, Justice Wynn, who has slipped into a coma, and at stake is the critical swing vote in a controversial court case and there's also a potential conspiracy that reaches to the highest levels of government.

So even though you got the storyline from your friend, what did you bring to this from your own political career and your own career as a lawyer?

SA: Well, what Theresa told me about was more of a question that she raised. She said, "Have you thought about the fact that Article III of the Constitution does not provide for the removal of a Supreme Court justice for any reason other than high crimes or misdemeanors?" And I said, "What do you mean?" I hadn't really thought of it. And so we were talking about the fact that you could remove a president through the 25th Amendment, that the election cycle for senators and for House members meant that there was an endpoint to their service, that a Supreme Court justice, a federal judge, has a lifetime appointment.

And it was really that question that stuck with me. It was less the storyline, it was more just, "Have you thought about this?" And she, I think, much to my surprise, understood how my mind worked even better than I did, because that question just stuck with me and we had lunch and by the time I got home, I was ready to write the first scene and that was a scene with Justice Wynn.

Part of it was the idea of comas and the fact that the Founding Fathers never imagined a coma. When you passed away, you passed away, and if you were in a coma, the machinery it takes to keep a person alive these days simply was never conceived of.

I think the other pieces, though, the "what would it take to create a case that would rise to this level of intrigue" was something that I pulled from a story I'd read about the Exon-Florio Act and how it treated anytime an international corporation wanted to do something in America, it created this mechanism that gave the president this exceptional power. And I thought about what I knew of the court and how, essentially for most of my adult life, fractured the court has been. I think all of those pieces added up, and over time I just layered onto it more and more of my understanding of how politics works, how government works, which are two very different things, and then, you know, because I really loved it.

I've a master's degree in public policy, and I mention that only because I actually studied how bureaucracy works. I interned for the EPA and for the Office of Management and Budget, and so really understanding just how much an intern could do and how much information is embedded in these mammoth bureaucracies that we have, just how much of the world gets lost on pieces of paper, those are all things I think have been swirling through me for a long time, and this was a chance to bring them all together.

MH: Cool. You mentioned the advances in medical technology to keep Howard Wynn alive and there's also a lot of scientific elements to the story. Did you have to do a lot of research to get those points right?

SA: Oh, absolutely. I love reading, I love television and movies, I love good storytelling. But the most dangerous part of telling a good story is getting it almost right. You can appropriate and you can manipulate, but you gotta get the basics correct.

And so for me, it's always about doing as much research as I can so that even if I'm doing something fantastical with it, the foundations are true, the foundations are real.

Now, I'm very lucky. I'm the second of six kids and each of my siblings has an expertise, so it saves me a lot of research time. I did my research, for example, on the scientific piece, to figure out what I wanted to do, but then I would test my theories against my youngest sister, Jeanine, who at the time was working for the CDC and she's an evolutionary biologist. So I'm like, well, I want this disease to do this, what's the incubation time? Is it okay to say this? And she's like, "No, that's too fast." So she would serve as sort of not only a source of information, but she was a good testing and sounding board.

The same thing is true for my sister Leslie, who is a judge and is really the lawyer in the family. When I'm writing about the clerk's life, I'm like, okay, does a clerk do this? Would a clerk have access to this? How would she answer this question? So, yes, I do copious amounts of research.

MH: Got it. It's great to have that in-house knowledge right there in your own family.

SA: All I have to do is buy them dinner. It's amazing.

MH: Yeah, true. So one of the tension points in this story is of Avery having the authority of being a guardian for a Supreme Court justice, yet having no real power in the midst of the political drama swirling around in DC. She's going up against Homeland Security, the FBI, local law enforcement, and eventually the president of the United States. Did you identify with Avery's struggle in any way?

SA: Oh, absolutely. One of the things you learn, particularly as a young person in any position where you have slightly more access than you expected, is that you may have responsibility but you have no authority, you have no power. It happened to me when I was an intern for one of the government agencies I worked for. I ended up with this portfolio that was well outside of my capacity, but I was the person who was around and I was the one given the responsibility, but all of the big decisions, I had no authority to make it happen. But they expected me to get it done.

"Once you get past the hardship of not being able to make it perfect, you then can focus on making it right."

It was my first encounter with the fact that I had no real power. My name wasn't going to be on the final product, I was going to be responsible for the data that I created or gathered, but I couldn't make anyone respond, I couldn't force anyone to engage with me, I couldn't even buy my own plane ticket to go and do the investigatory work.

And so, for me, it was about amplifying that experience and the experience you have as a young lawyer, as a young political operative. I think almost any area of importance that you enter before you are the person who has the ability to make decisions, if you moved just a smidge higher on the totem pole, you will find yourself at some point with absolute responsibility and absolutely no power, and the disconnect does not concern those who have power at all.

MH: But I feel like this probably gave you an opportunity, you think, for some retribution? Because there is this power of Avery as the underdog going head-to-head to take down corruption at the highest levels of government. When she stands before the Supreme Court to argue her case, you just feel this swell of emotion for her, like, you go girl.

SA: Well, and that's exactly it. Part of it is that once you get past the hardship of not being able to make it perfect, you then can focus on making it right. And that became her mission. One of the things I really loved about Avery—I mean, yes, I made her up, but she did what she wanted—was that Avery chose to do this; it wasn't that she didn't have the option of giving up power of attorney, it wasn't that she at multiple stages couldn't have abdicated responsibility. It's that moment when you decide you're going to ask because that's the thing that you have to do, that's the thing that you need to do, but it's an affirmative choice as opposed to being backed into a corner, that is that underdog moment, that moment where then the victory is yours, the victory is real, because you have navigated these challenges, not because you had to, but because you couldn't let yourself not do it.

MH: You have a great way of letting readers know that your characters are Black without defining them by their Blackness. For instance, I honestly wasn't even sure that Avery was Black until you mentioned that she went to Spelman, and then I was like, ah, well, there you have it. She went to a historically Black college. Yes. So how do you navigate that line? Is it a conscious decision to not explicitly define your characters by their race?

SA: Race matters and it is disingenuous to write stories, especially contemporary fiction, without acknowledging that the race of the character is going to change the interactions they have.

My point is that it doesn't wholly define who they are to the exclusion of their other aspects, and so yes, her race matters, her gender matters, and those were both very intentional of me. But what I grew up disliking so much was that in books that I read for most of my life, the only time you read about race as an explicit attribute was when it was being used to create others. The presumption was a universality of Whiteness and they would then describe the Native American character or the Latino character or the Black character or the Asian American character.

They would only ascribe race to someone who wasn't White. And that always chafed at me, both as a reader, because it pushes you out of the story. You're immersing yourself. And whether I'm in the heather with the Brontës or I'm out in outer space, I should get to have the same experience of seeing myself in the story and not be jarred out of participation because you find what I look like and who I am to be a departure from the narrative.

And so for me it is, yes. I gave hints throughout the story, and I wasn't trying to be coy. Her mom is White, her dad is Black. There is a scene where I describe her father. Howard Wynn is Black. Teresa Roseborough is Black. For me, the other piece of this is that it should be something that is not considered a departure to have multiple characters in this kind of book be African American or Latino or White. It should be possible that the world that I created, with the exception of the creation of, you know, this chromosomal time bomb that writ large this story should be possible and that characters, as I see them, could be where they are, doing what they do.

MH: And it very much reflects the real life, what's going on in America. So you have Adenrele Ojo performing While Justice Sleeps and she is one of my favorite narrators. Did you have any knowledge of her work before she did this book?

SA: So I have not been as immersed in audiobooks as I should be, but I have a younger sister who loves them, and so when I was talking to her about these potential artists, she knew of her. And then when I got the opportunity to listen to various artists who were under consideration, her voice just captured it for me from the very beginning. I needed someone who has both that resonant tone that comes to her voice as she is narrating, but also her ability to characterize, and I felt she was an extraordinary choice.

MH: Her voices that she does, like how she brings the accents, and—

SA: Yeah.

MH: At one point I was listening and I thought, wait, did someone else just come into the story? Or is this still her? I mean, she's fantastic, very authentic.

SA: Well, I want to say this about audiobooks: I have grown to love them more and more the more my life has become complicated, and it's an amazing talent, having recorded my own book. I don't understand how people do this for a living. This, to be able to navigate and to be so compelling so consistently, is just a testament to the artistry of those who do this work.

"In books that I read for most of my life, the only time you read about race as an explicit attribute was when it was being used to create others."

MH: You narrated your two nonfiction works, but why did you decide to have another performer narrate While Justice Sleeps?

SA: I love this story and I know their voices, but I wanted to hear someone else interpret what I'd written. I've lived with these characters for a decade, and what is so exciting to me about this book finally coming to life is to see how other people engage them, how they get to know them, how they think of them, how they refer to them, and when you think of a voice actor doing this work, the nuance and the intentionality is so incredibly important. I wanted to hear what someone else could see in what I wrote.

MH: What would you say about the power of voice to persuade, connect, and share experiences?

SA: My work is about voice and that's as both actual and metaphorical, whether it's the work I do as an activist and a politician, which is always about either standing as someone's voice. When you're a representative, you are speaking for others; when you're engaging people in their democracy, you're encouraging them to speak up for themselves; when you are telling stories, you are relaying the voices in your head and giving them form and substance and a storyline; and even in my entrepreneurial work, when my businesses exist, they are there to answer questions and to give people solutions to questions they have not been able to solve, and that all comes back to voice, back to being heard, back to being recognized, and back to being able to create.

MH: You've written eight romance novels under the pen name Selena Montgomery, but why did you publish While Justice Sleeps under your own name and not use a pseudonym?

SA: When I started publishing, it was 1999 that I finished my first novel. It was also 1999 that I finished my first journal article on the operational dissonance of the unrelated business income tax. I did both of those in the same year and that's around the time that Google became a thing. A dear friend of mine told me to Google myself. I put my name in and up popped an article I'd written in high school that was in the Journal of the Astronomical Society of the Atlantic on Mesopotamian astronomy, because for a minute, I thought I'd be a physicist.

All of which is to say that at the time that I was going forth, it became very clear to me that merging my identities as romance novelist and tax aficionado would be weird and I was asking people to take a lot on faith, and so it was easier for me to say, "Okay, as a matter of branding, Selena Montgomery needs to exist as a romance writer and Stacey Abrams will exist as a tax person," because I wanted to write in both spaces, and as I've said jokingly and hopefully with never offense, I can't imagine people looking at Alan Greenspan thinking, "I wanna read a romance novel by him."

So it was just easier to keep the identities separate. Plus, Selena Montgomery sounded more like a romance novelist than Stacey Abrams.

MH: Cool. Why do you enjoy writing suspense? Because even your romance novels are romantic suspense.

SA: I grew up watching James Bond and General Hospital when it was Luke and Laura and Robert and Anna. My favorite romance novels were always the more exciting thriller ones. I love the tension of storytelling where the odds are always in doubt and people are always in jeopardy and really trying to find a way to make puzzles make sense.

And so suspense is the perfect genre for me. Whether it's romantic suspense or legal thrillers, I'm always intrigued by how do you create this problem that seems thorny and wholly impossible to solve and then spend the rest of the book figuring out the solution or writing myself into a corner that leads the book to sit in the drawer for 10 years. Joking, joking.

MH: Joking.

SA: Yeah, joking. I solved the problem. I solved the While Justice Sleeps problem the first time I wrote it.

MH: Okay. That's great. So what are you working on next? Do you think you'll write another thriller or go back to being Selena Montgomery or maybe write a memoir?

SA: Writing a memoir is highly, highly, highly unlikely. But writing more fiction is absolutely in the cards, and writing more nonfiction. I think I am going to be obliged to write the third book in the Selena Montgomery trilogy that I ended abruptly after two books because I couldn't come to an agreement with my publisher about the timetable for the third one. However, now that more people are reading Selena Montgomery, I am getting more questions about where Julia's story is, so I'm going to get Julia's story done, and then I'm certainly excited about writing future thrillers. I think Avery has a lot more story to tell, and gotta figure out what's going on in the rest of the world.

MH: That would be amazing to bring her back for another thriller. Whatever it is, we can't wait to hear it. And I know Audible listeners will enjoy While Justice Sleeps just as much as I did. Thank you so much, Stacey, for joining us today. It's been a real pleasure.

SA: Margaret, it's been my delight. Thank you.