Note: Text has been edited and may not match audio exactly.

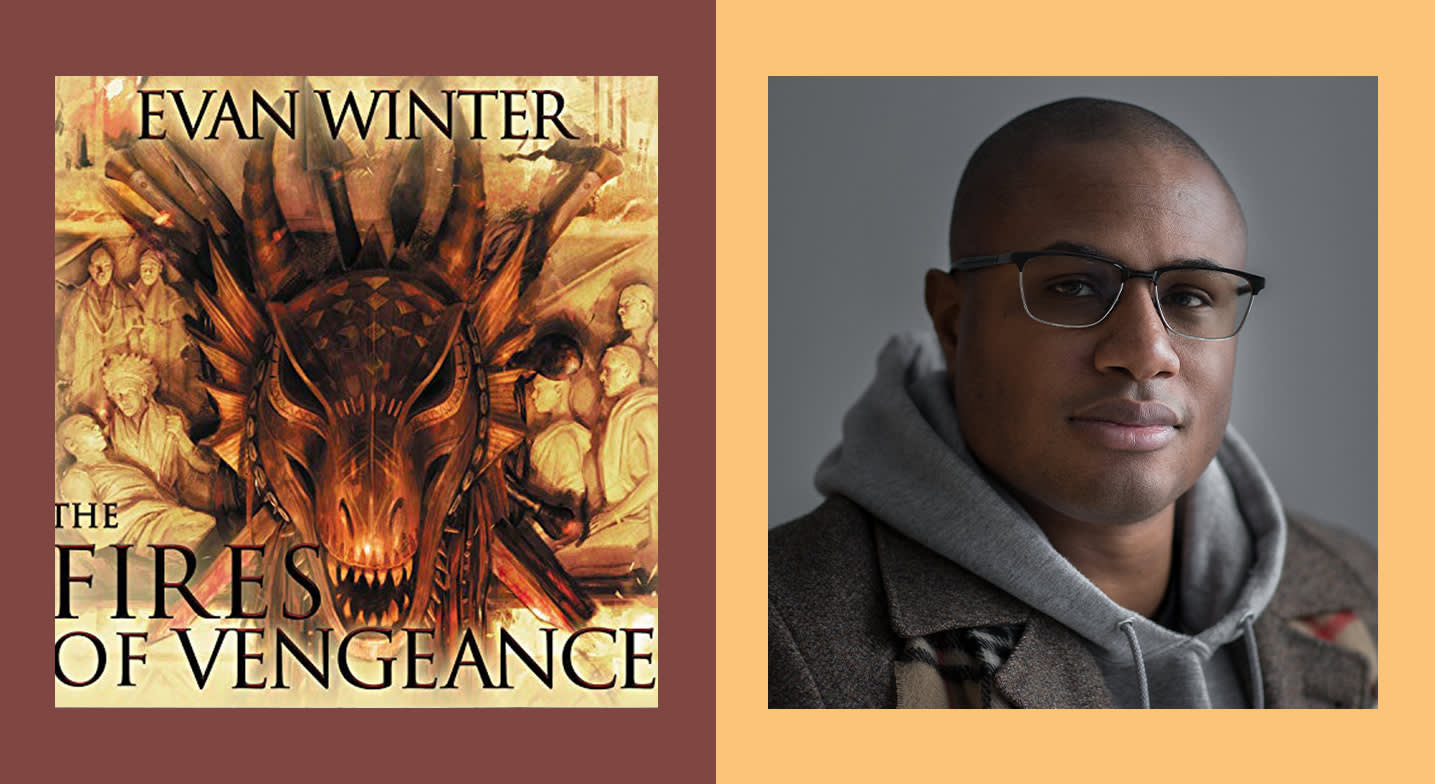

Melissa Bendixen: Hi, listeners. This is Audible Editor Melissa Bendixen, and here with me today is Evan Winter, author of The Burning series. The first of which, The Rage of Dragons, was named by Time Magazine as one of the 100 best fantasy books of all time. It was also one of Audible's top fantasies of 2019. We're here to discuss book two in the series, The Fires of Vengeance, which was released in 2020. Welcome, Evan.

Evan Winter: Thank you so much for having me, Melissa. It's an absolute pleasure to be here. I am a big fan of Audible and of audiobooks in general, and it's a wonderful way to listen to stories and it sort of makes me always feel like it hearkens back to the original way that stories were first told around that campfire, in caves thousands and thousands of years ago. So it's one of the purest ways to experience a story. I'm very excited to be here with you today.

MB: Wow. Thank you so much. Of course I feel the same way. I'm an Audible editor, so I'm an audiobook addict and it's always nice to meet an author who feels the same way.

First off, I have to say congratulations on making the Time 100 best fantasy books of all time. Listeners might be surprised to learn that you originally self-published The Rage of Dragons. I wanted to ask what that journey has been like for you. Can you tell us a little bit about how you arrived here from there?

EW: Yeah, I definitely can. Before I get into that, I'll even jump into the Time Magazine thing. In a lot of the different sort of awards or accolades that you get, you find out a little bit in advance of actually receiving the awards. Your PR people or whatever give you a bit of a heads-up. It wasn't the case with Time. I woke up one day and someone was like, "Hey, look at this. This is pretty cool." It absolutely blew my entire mind. I literally thought it was a scam or a joke for the first little bit, because I couldn't believe that that was something that was happening. So that made my year. It was an amazing, amazing thing to just wake up to and experience. Very, very honored about that.

"The most important thing about having diverse voices is that we as readers get to learn about the experiences, opinions, perspectives, realities that we might not otherwise be exposed to."

In terms of publishing, yeah, I did self-publish first and that was a very important thing it felt like for me to do. I've always, always wanted to write, but originally you sort of start to get to this place where you think to yourself, is writing even a real career that people actually do? And it's really hard to believe that that's something that you can sort of fall into or even aspire towards realistically and make a living doing it. So I wanted to do that since I was a little kid. I went into a lot of different industries. I ended up working in film actually because it was probably the closest, I felt, that I could reasonably come to being able to tell stories or being some participant in the telling of stories. And so I worked as a director in film, primarily music videos. I did that for many years and loved it, but it still wasn't quite the storytelling that I wanted to do.

And so when I had kind of a gap year—I was getting older, but had a gap year in my schedule—and I knew that I had probably about one year where I didn't absolutely need to earn money. And I was very privileged to be in that position. I fully acknowledge that. But I had that period and I said to myself, "What's the major thing that I would regret if I didn't get the chance to do it before I shuffle off this mortal coil?" And it really was to write a book, to tell the stories that I feel like were bubbling up inside my head all the time. So what I did is, I basically sat down to try to write a book and tried to write the story that would've made the most impact and the most difference in my life if I had come to it as a reader and picked it up off the shelf or was lucky enough to find it on Audible and listen to it.

And so I wrote that. That was The Rage of Dragons. I wrote that also to see if I even enjoy the process of writing or if it was just a pipe dream. Like just something that I thought, oh, this would be cool. But when you actually sit down and you have to do the daily grind of it, it sucks. It didn't suck. I fell in love with the entire thing and the process of immersing myself in the world of the writing, to even all of the technical sort of things that go with publishing. And when I was all done I had to figure out, well, how do I get this out there so people besides me and my mom can read it?

And I went to Amazon, I went to Amazon's KDP, Kindle Direct Publishing, because it offered a way for me to put the book up there and present it directly to readers. I didn't have to go through gatekeepers who, to be honest, I worried would look at this world populated with Black characters, set in a secondary Africa, and they might say, "You know what, it's interesting, but it's not for me." Or they might say, "I don't quite get the voice or the ideas behind it" or "I don't connect to the story or the characters." I wanted to go right to readers so that they could tell me if they connected because that's who I was really writing for, myself and the readers.

So I self-published on Amazon and the platform is set up in such a way that with some marketing, with a little bit of a push that Reddit's r/Fantasy—it's a massive subgroup of fantasy readers—they gave it a massive push and it sort of climbed up Amazon's charts. It became a lot more visible. And out of nowhere, a senior editor named Brit Hvide from Orbit saw that people were talking about the book, decided, given her very busy schedule, to pick up this book and read it. And then got my contact information and gave me a call.

MB: That's quite the story. That's pretty awesome that you went through that journey. When did you start writing The Fires of Vengeance?

EW: So The Rage of Dragons was started in 2017 and actually published that same year. It was a very quick schedule for that. That was self-imposed because I knew I only had the year to go before I had to start looking for a "real job" again. And then Orbit picked up the book and they bought the entire series. It's a four-book series and they republished [book one] in 2019 in July. And so I was writing The Fires of Vengeance primarily, I guess, in the end of 2018 into 2019. And it took me a lot longer than I expected because The Rage of Dragons came out pretty quick and I managed to get it all done in a year. And I was like, oh, this is how this happens. This is what the creative process is like in terms of writing.

But book twos kind of kick your butt a bit. They're not easy, because I think there's the expectation that you want to live up to for all the readers who enjoyed book one. You really want to live up to that expectation. You really want to deepen the world, the characters, the story as best one's able given, hopefully, some sort of leveling up in craft that comes from having already written one book. So it was hard to write book two, but also incredibly rewarding. And I think that The Rage of Dragons is so, so special to me, but I think that I actually even enjoy as an author-reader The Fires of Vengeance more because it's telling more of the story that we're leading towards with the big push into book three and then the maximum, explosive climax of book four.

MB: Yeah, I've been very curious about that. I'm sure writing book two was so different from writing book one for you and it sounds like it was. And I was even wondering if you were writing book two while book one was coming out to so much success and acclaim and if that affected your writing process there as well. It sounds like book two came with its own challenges because book ones, they're always the beginning, the origin story, which kind of writes itself. But book two is now when you can really get into what's the larger world and start diving into that deeper part of it.

EW: That's exactly it and exactly what happened. And in terms of even writing, my plan was again, I was self-publishing and a large part of what's important in self-publishing, in a way that's not in trade publishing, is that you're often sort of pushed to publish faster. I mean, you can do that because you can hit "publish" whenever you want. And it also works really well with Amazon's platform that readers are able to pick up that book quicker and keep going through the series. So my plan was to write book one and then write book two. But I did sort of get sidetracked by the fact that the book was doing better than I expected, which is an incredibly good problem to have, don't get me wrong. But I was surprised by how difficult it was to get right back on that horse and get book two done and dusted. And yeah, just like you said, the expectations, the new reality of having a book already out there and trying to manage that process as well. And then with the contract that came up from Orbit, that threw me for a loop as well.

MB: You quote your son as the reason you decided to write fantasy that centered around African culture, so he could grow up seeing himself in fantasy novels. And indeed there's been more African-inspired fantasy publishing as of late. How are you feeling about these developments in the fantasy genre and your contribution to it? Where do you think it needs to go next?

EW: Thanks for the question. That's a great one. I think that it's really important to see all of these kinds of stories, because the strange thing about storytelling is that when we're reading a book, we almost experience and learn from the story as if it is a thing that's actually happening to us. And I believe someone's going to have to go Google this and make sure I'm not wrong, but I remember reading a study that shows that the areas of the brain that light up when you're reading a story about something are actually the same areas of the brain that light up when you're learning a new skill or actually physically are really doing something to yourself.

The experience is like—Stephen King talks about reading as if it's the closest thing we have to actual telepathy. He can talk about a house or something, and the reader, divided by years of time possibly and thousands of miles, will picture a house somewhat similar to the house that he's describing and go through that same journey that he's trying to tell. One of the major powers of reading is that it is a learning tool as well for all of us.

The most important thing about having diverse voices is that we as readers get to learn about the experiences, opinions, perspectives, realities that we might not otherwise be exposed to. And I would like to think, and I would hope, that that makes us all more fully rounded human beings, more empathetic and more understanding of the struggles that we all have and the shared goals and shared desires that we all have.

MB: They say that the person who has not read only lives one life and the person who reads lives a thousand lives.

EW: Yep. One of my favorite quotes. I love that.

MB: Yeah. I kind of live by that quote and I say it to anyone who may not be a constant reader, like we are.

Let's talk about what inspired you to become an author. I've read, and you have in your bio, that you've always been a fantasy reader. And you've always been a storyteller in your life, but The Rage of Dragons was your first attempt at a novel, if I'm correct, which is especially impressive considering how masterfully it came together. I'm curious if writing has always been a part of your life and if you've attempted to write novels or short stories before?

EW: First of all, thank you for the incredibly kind words. I think that writing has always been a part of my life, although I've never written novels per se or short stories before really, except for assignments in school or something, and again, not a novel, but just like little essays or short stories in English class. But writing has always even been a part of my professional life because as a music video director, you have to pitch [what’s] called the treatment, which is basically the concept, the script for the music video that you're planning to make.

I kind of always ended up getting myself in trouble—sort of good trouble but trouble—because I would have these ambitious story-oriented ideas that were next-to impossible to pull off on the amount of money that we would have from the label to make the videos. And it was me trying to really stretch and be like, "Oh no, I got this. We're going to tell this whole story about this person doing this. And there's this whole arc of character and story and world." And they'd be like, "You cannot even come close to achieving that on the amount of money we have, you need to calm down."

The funny thing is that I loved directing, it was a lot of fun. But it always felt… I'm left-handed, so directing always felt like trying to write with my right hand. I could do it. I have to focus on it. And it was a bit of a struggle, but I always felt like if I kept trying, I could probably get better. The writing of the treatment, the writing of the scripts for the music videos, and even sitting down to write Rage, it felt like I finally had picked up a pen or pencil with the right hand, like with my left hand being my right hand, with my dominant hand, it finally felt like I was doing something that felt natural to me, that felt very, very normal, and an extension of just the way that I think.

I don't say that to suggest that if that's not how it feels to somebody else out there in the world trying to write right now that they can't be the writer they hope to be in the world. I just say it to suggest that for me, it finally felt like coming home. Like all of my professional life, all of my educational life, I've been doing different things and they all felt like variations of toughness and sort of like trying to find who I was. Sitting down to write fiction felt like I'd found who I was supposed to be.

MB: Are you a full-time writer now? Or do you have your side projects still going on?

EW: I am incredibly fortunate in that I am currently a full-time writer. It would be my hope to continue that path for the rest of my life, but we'll take it as it comes and we'll see what happens. But again, I'm very fortunate. I ended up almost winning a bit of a lottery ticket and I'm aware of that. It's not something that I could… Hopefully you'll never see me standing up on a stage somewhere trying to say, "And this is how you do this." Because I don't know. Right place, right time. I definitely work to try to create the best story that I could. But so much of this disappears and doesn't happen if just on the day that Brit, my editor, if she just didn't go on the internet that day and didn't hop on Reddit and see that someone was talking about the book, none of this would have happened really, right? We're not talking right now if that one thing doesn't happen. And it's so odd to think about that, how a million little choices can change the course of something so dramatically. So yeah, I feel incredibly fortunate.

MB: It's true. But you also have in a way been training for this your entire life, and you've always been a storyteller and you have the skill and there's luck, but you wrote a great book. So it's getting the attention it deserves. Or you're writing a great series and it's getting the attention it deserves.

EW: Thank you.

MB: I want to turn a little bit to the plot of The Fires of Vengeance and the series as a whole. Tau has to overcome some of the worst odds I've ever seen a fantasy hero face and yet one reason why I've been so impressed with the series so far is the way you believably pull off having him overcome those odds. There seems to be this delicate formula or dance for doing this right and I'm wondering, what kinds of things did you consider in order to make Tau's story both high stakes and believable?

EW: That's a great question. I think one person's high stakes but believable ends up feeling like another reader's plot armor. I did try very hard to tell the story as honestly as I could. And a lot of it falls, I think, from my overall perspective on history and my basic worldview, which is that the common sort of mono myth that we're told in the West is the idea of the great man. History moves based on the actions of great men. That's the idea, that's the story. And although I'm telling a story about a character like Tau, who does do great things, a lot of the events that happen in the book, a lot of the changes, aren't due necessarily to his actions alone. His actions don't bend to the story, they affect it, but the actions of his friends, his compatriots, the actions of the Queen of the gifted that surround him all affect the way that things are going.

I really tried hard to tell the story in a way that felt honest to my understanding of how history actually moves, which is not based on great men changing—particularly in the way that we read history—great men from the West changing and molding the world as it is today. There are so many other factors that come into play, and yes, the victors write history, so to speak, so we end up seeing stories from a certain perspective, but the reality is that there are so many other perspectives and voices that went into making history be what it is. And so I'm trying hard to tell a story that reads as truly to my understanding as I can.

MB: I see. I am also curious about how you put together the world of The Burning series. What do you turn to, where do you draw from, to build your world?

EW: I think I try to draw from, again, what I know, what I enjoy in fantasy books, enjoy in fiction, but also is primarily what I know and the way that… I want to say the way that I write, but again, I'm only two books in and writing a third. So I'm still fairly new to this game. But the way that I enjoy trying to write is to ask questions and then to explore them through the act of telling stories. It helps me examine the questions. It helps me understand the questions. I don't think I ever get answers, because answers are maybe beyond the scope of what it is that I'm capable of achieving through the storytelling. But I definitely come away after I wrote The Rage of Dragons, after I wrote The Fires of Vengeance, I come away feeling as if I've explored these questions and have a better understanding, insofar at least for myself, about the human condition.

"Prentice is a genius and he's an artist of what he does. To listen to that work is transformative for me. I'm so grateful that he's there doing the work."

Again, I always try to say this, not in some kind of objective sense. I don't think I actually have the answer to anything. It's just that exploring the way that we move through life helps me understand my own life better. And in terms of world-building then, everything that I put into the worlds, every part of Xidda comes from some element of the questions I'm trying to ask. They build out of the narrative, they build out of the story because the story builds out of the thing I'm trying to explore. One example is that so much of this series is about cycles of violence. Almost everything that exists in this world exists because the story that's being told is about cycles of violence, so the things that must make those cycles of violence repeat and repeat and repeat exists natively to the world. And that's what helps define what the world must be.

Another thing that I've recently realized, and didn't at the very outset of this, is that so much of this is about parents and their children. In particular with someone like Tau being a lead character, fathers and sons, and that sort of relationship, and what does that mean, and where can it go wrong, and where can it go right? And the idea of, are we responsible for the sins of the father or the mother? And so again, so much of the world, its history, its people, its circumstances, drive up from out of that idea, that question.

MB: And I see how in your series, the relationship between parents, you can kind of see how that's reflective of the society as a whole or how it's like a chicken and an egg and they feed each other, the relationship between the parents and the society and how they treat each other. One thing I wanted to—this is not question, but this is a speculation—I wanted to leave this like dot, dot, dot to see what you might say after I say this is, we can clearly see that the Xiddeen are a people of honor and equality, much more so than Tau's own people in a way, who are severely divided by class. As we're saying with the relationship between the parents and the relationship they are to each other as a society, it almost makes me wonder if Tau is even on the right side of this fight. And that is where I will leave this dot, dot, dot.

EW: And that is another absolutely wonderful question.

MB: Okay. All right. Well, books three and four, here we come. So Prentice Onayemi narrates your books impeccably and his performance enriches the story with the way he captures those African dialects. And you got him back for book two. What's it been like having him narrate your words?

EW: Okay, I'm going to get gushy for a second here.

MB: Please do.

EW: I'm going to do it. I'm going to go all in on this. Prentice Onayemi was my absolute number-one first choice to narrate the books. And I feel so grateful to have Hachette Audio make that a reality. He was the voice I wanted. He was the sound I wanted for this story so badly. And it's to the point where I listened to the work and it makes me feel as if I'm finding new things in the story. I'm supposed to be the one who wrote it, but he has made it his own in another way and I adore that. And part of my process at this point in writing the next book is, I listen to the audiobook. I don't go back and read the books necessarily. I have to a little bit, but I listen to the audiobook narrated by Prentice to get me back into the world, to help me understand the nuances of it.

And I started to write a little bit with the way that he crafted the characters in mind. So there's almost a slight symbiotic process that's happening. And again, this is why I feel so strongly about the value of audiobooks. It's something that I came to a little bit later on in my own life, but there is such a powerful part of storytelling in listening to a story actually being told, which is why we call it storytelling to a certain extent. And Prentice is a genius and he's an artist of what he does. To listen to that work is transformative for me. I'm so grateful that he's there doing the work.

MB: One thing that I really love about the audio experience is that you have two art forms layered on top of each other and it's level one, level two. When you have a great narrator and when you have a great story, they are even greater together. It's more than the sum of its parts. And I feel like with your partnership with Prentice Onayemi it's that perfect symbiotic relationship that you are looking for in an audiobook series and in an audio experience as a whole. I completely agree, and I love that you feel that about his work and him as a narrator.

EW: Obviously it's always an art form, but then sometimes you run into somebody who's like an Oscar-winning performer. And in this case, for the series, I completely feel that about Prentice Onayemi. I think he's remarkably skilled and what he's doing is bringing art. It's not just reading, it's not at all. People have to understand that. It's an art form that he's bringing, he's bringing a performance to the book. When you listen to narratives like that, you are actually getting something extra.

There's another—maybe I should only be talking about my stuff, but I'm going to talk about something else—Joe Abercrombie's books, narrative by Steven Pacey, do that for me as well. Actually, I'm into the new series that he's doing right now. I started reading A Little Hatred and then I got the audiobook from Audible and I was listening to Steven Pacey narrate it, and at one point I had the book and I said, "Okay, I'm going to go back to reading." I started reading and I was like, "No, the voices in my head suck. And they're nowhere near as good as what Steven Pacey can do." So I actually went back to the audiobook and I'm going to finish that entire series on audio because, honestly, it's better that way for me than physically picking up the book and reading it. That's how powerful the right audiobook narrator can be for a series, I feel like.

MB: So true. How did you end up coming to audio and how did you end up getting so passionate about audio? I'm curious.

EW: It's because for a while there, before I actually had the chance to write Rage, I got a job as the creative director of a massive multinational infrastructure firm, and the job site, where I had to go into the office, was about an hour away from home, but in traffic the commute was about an hour and a half on some bad days. So I got heavy into podcasts and that's when I actually did a lot of my learning about the potential in self-publishing. I listened to a bunch of podcasts on publishing and then got into self-publishing. Joanna Penn's podcast was one of them, for example. And then when I ran out of podcasts, I started moving into biographies or autobiographies and I was listening to them. I would download them from Audible and I would listen to different autobiographies by different narrators.

"Even if you are not an audiobook listener, this might be the thing to convert you over because every so often you find something that just opens the door a crack wider than you thought it would have opened for you before. I think that Prentice Onayemi's narration is one of those kinds of performances."

It was just such a good way to keep up with my reading, even though three hours out of every single workday or weekday was burned away by sitting in a car. And so that made that hour and a half each way, so three hours a day, so much more bearable. And I think it was then that I fell in love with audiobooks. Now, even though there's no commute, I still listen. And, I mean, it's a tough year for everybody. One of the inconsequential sort of fallouts for me—like it's very inconsequential, I fully know that—but I couldn't read. I couldn't read this year. And the book that got me back into reading this year was to sit there and listen to the audiobook for The Trouble With Peace by Joe Abercrombie, which Steven Pacey narrated.

An audiobook got me back into reading this year. So I very much appreciate the power of that and what that allows people to do, because reading is so important, like what you said, Melissa, about you live more lives by being able to do it. And I felt like I was losing that a bit because it was so hard to get into fiction in 2020.… I do it [listening to audiobooks] when I'm doing the dishes. Sometimes I'll just lie there and listen, because that's my preferred way of consuming Joe Abercrombie's series

MB: Yeah. I think fantasy is a really great way to experience audio because so many people have this barrier in getting to know the world in fantasy and you have to do a lot of work when you're reading it upfront, but when you're listening, somebody else is doing the work for you and so it becomes so much easier to get into that world. And narrators also can convey the world; things like pronunciation, dialects, all that stuff is so important and that stuff comes up in fantasy so often too.

EW: I would have no idea how to pronounce any of the titles or names in Lord of the Rings if I didn't have an audiobook to go along with it, a lot of very tricky words in that. I'm being a little silly, but that's, I'm not going to say critique, but that's a comment that I get a lot with The Rage of Dragons is, readers unfamiliar with sort of the more African sounding names or words are like, "Well, I don't know how to say this or pronounce it," which is fine, that part's completely fine. And The audio can help with that. And you get to really experience those sounds.

But then I guess for some people, seeing the words that feel a little bit out of step with what they're used to becomes an actual turnoff. That's one of the actual struggles I get sometimes, of trying to bring elements of a culture that's not more, well, seen in the West to the West. If I can say that. And again, audio can help with that because it can be that sort of transition for folks who don't mind, but still might struggle. For folks who do mind, there's no transition that's going to make sense for them, they're just going to mind no matter what. But for folks who want to get that extra way, but not knowing how to pronounce things or how the sounds of things are supposed to go is bothersome, audio works really well.

MB: That's so true. Is there anything else that you would like to tell future, potential, or continuing listeners about your series in audio?

EW: Let's see. I think that I'm very much looking forward to all the new work that Prentice Onayemi's going to do on the series. I think he does very much bring it to life. This is maybe so bad to say, but I almost encourage anyone who would even want to pick up the book, at least give the audio a listen, because it is so well worth it. And even if you are not an audiobook listener, this might be the thing to convert you over because every so often you find something that just opens the door a crack wider than you thought it would have opened for you before. I think that Prentice Onayemi's narration is one of those kinds of performances. So definitely give the audio a try. Pick up the books too, if you want. I got no problem with that. But definitely give the audio a try. Listen to the sample even and see what kind of work is being done there, because it's amazing.

MB: Thank you so much for speaking with me today, Evan. As you can probably tell, I'm super pumped for books three and four in The Burning series, and I'm so glad the first two books have gotten the attention they deserve. Listeners, you can find The Rage of Dragons and The Fires of Vengeance on Audible.

EW: Thank you, Melissa. You were absolutely awesome. And such a pleasure. So thank you very, very much for making the time and for doing this with me. It means a lot.