Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

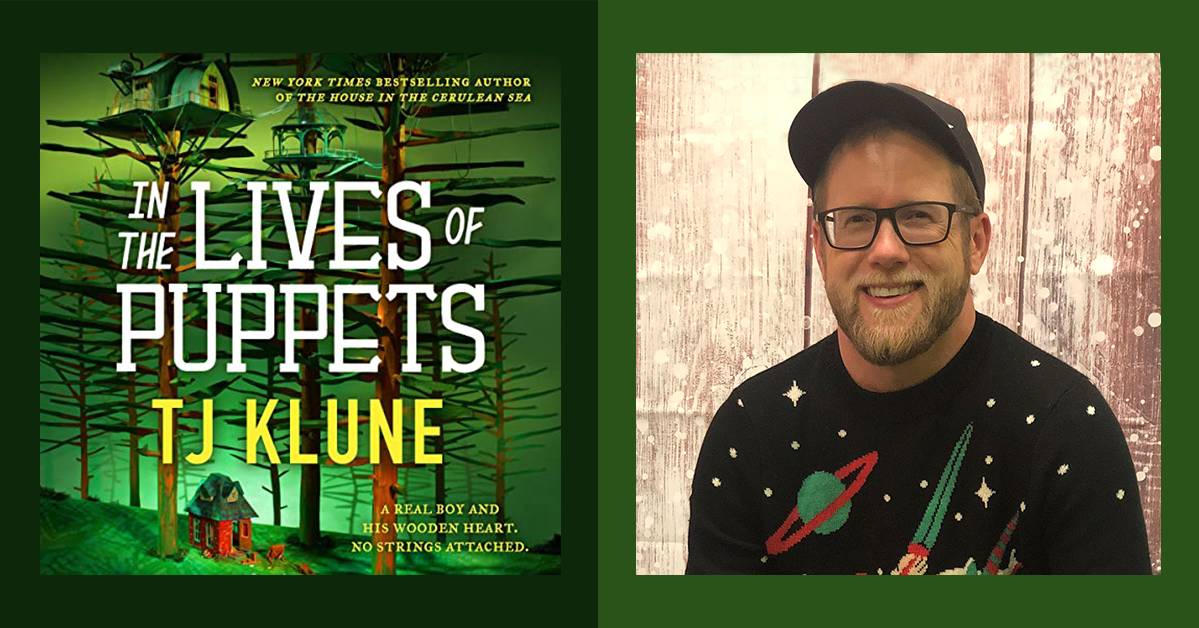

Michael Collina: Hi, I'm Audible Editor Michael Collina, and I'm so excited to be speaking with Lambda Literary Award-winning author TJ Klune about his new audiobook, In the Lives of Puppets. Thanks so much for being here, TJ.

TJ Klune: Thank you so much for having me, Michael. I appreciate it.

MC: Of course, we are so thrilled to have you. So, you have such a knack for writing stories that tackle some pretty heavy topics but still manage to tug at your listeners’ heartstrings in all of the best ways. And this latest one is no different. At its heart, In the Lives of Puppets is a retelling of the Adventures of Pinocchio, but it's also a love letter to literature and pop culture. There's a murderous nurse robot known as Nurse Ratched, a reference to One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest. And then our main character, Vic, feels like somewhat of a nod to Mary Shelley's Frankenstein. What inspired you to weave in all of these elements?

Add this interview to your Library:

TK: I love science fiction and fantasy as a whole. I love all aspects of it. It is what I read as a child. It's what I continue to read now. It is probably only second to horror in my love of the genre. And there is such an extraordinary history in the science fiction and fantasy genre. And if I can't pull from that history and try to fashion it into my own, what am I even doing? I'm so glad that you mentioned Mary Shelley's Frankenstein because that to me is probably in the top-five most important works in the English language, in my opinion. I mean, for those who aren't really aware, Mary Shelley essentially invented the science fiction genre at the age of 19 when she wrote Frankenstein. And then a couple of years later, she wrote what is rightly considered to be the first post-apocalyptic novel. And this is all done by this young queer goth woman who, at the time when she was writing it was frowned upon for women to be doing anything, much less telling stories about monsters and evil and the follies of man.

And I wanted to pull from this entire history that we had, not just in fiction, even though there's large parts of that too, but from movies and TV shows. I mean, you have WALL-E, you have The Swiss Family Robinson, you have elements of Stanley Kubrick and Steven Spielberg in A.I. You have just all these different bits and pieces that I just plucked from in order to fashion the story that I wanted to tell with this. And this is a love letter not only to these characters but to the genre that has given me so much, because science fiction and fantasy, it's unlike anything else in the world.

MC: I love that. And despite all of those influences, In the Lives of Puppets, it's almost a subversion of the Pinocchio story where a human boy is surrounded by androids and machines. So, it feels like Pinocchio stories are having a bit of a moment right now.

TK: That's an understatement, right? There I am wanting to write a Pinocchio story, then all of a sudden, "Hey, guess what? Here's 18 different Pinocchio movies, congratulations."

MC: Yeah, and most notably there's Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio, which was set in fascist Italy. And now with your book, which is set in the far future, what was it about the Pinocchio story that first interested you?

TK: So, most people, especially in America, only know Pinocchio probably from the Disney version. And I think that a lot of our fairy tales and fables that we know have unfortunately been seen through a Disney lens. And you have that bright, beautiful sheen on it. Can it have moments of darkness? Yes. If you remember the Disney version of Pinocchio, you probably remember the scene with the donkeys and how people were turning into donkeys. And that's pretty frightening in the movie. But the story itself, [Carlo] Collodi's, like most fairy tales, like most fables, they come from a much darker place and they have a darker undercurrent to it.

One of my favorite anecdotes that I learned about while researching Pinocchio—because I didn't just read the story, I wanted to know everything about it, how it came to be—but one of my favorite anecdotes that I came across was this: The Adventures of Pinocchio, Collodi's original version, was a serial. It was going to be published weekly or monthly in sections, and that's how they used to do stories like that. And when he wrote the original story, his editor read it and said, "This is way too dark. You wrote a story for children.” But in the original version, he kills Pinocchio. Pinocchio is dead and hung from a tree at the very end of the story, and that's it! That's the end. It's for his hubris of wanting to become a real boy. And his editor said, “You can't do this to children.” So, he rewrote the story as we know it now. And A) I just find it fascinating that even editors back then were like, "Yeah, this is what you kind of have to do," because I know all about that. And B) It's just the fact that there's this level of darkness that we don't see, but they're there to teach lessons. They are there to remind us of our humanity. And that's what I wanted to do. I wanted to take this story and go back to the darkness of it, to go to the roots.

And in going with my previous books, The House in the Cerulean Sea and Under the Whispering Door, I gave them, those characters, a place to belong, a place to be happy, a place to find themselves and their family. In this book, in In the Lives of Puppets, I start with that, and then I take it all away. And what would that look like to a group of people who are not all people? What would that look like to them to have to figure out what you do next? What do you do when you’ve forgotten all that you know? And that's what this book is about.

MC: And I also feel like just A.I. and androids and robots, it feels like the perfect way to modernize Pinocchio. You know, swapping out the traditional puppet with machines. So, with the rise of artificial intelligence and just the overall robotization of our world, what are your thoughts on that rise?

TK: It's frightening. It's very, very frightening. And I think I take a stance on that in the book, but at the same time, I also allow the characters of Hap and Gio and Nurse Ratched and Rambo, all machines, to find their humanity. And it may not be humanity as we think it, but it is recognizable as such, and the differences are so minute that they are negligible. And these days, we hear a lot about ChatGPT and all of these artificial programs that people can write. And I just want to ask, does nobody remember Skynet from Terminator? Jesus. Look, we've been warned time and time again about what stuff like this will happen. Science fiction and fantasy not only has been a genre about telling stories, but it has also been a genre about warning, about our hubris, and what we do when we mess with things that we don't always understand.

I'm a big video gamer. I love playing video games. And I was just recently reading a story about a major video game company starting to use artificial intelligence in the writing of their games, not to actually write the full games, but to give prompts for the actual writers to then take and put in the stories. And I'm just thinking that is a slippery slope, because what happens when you start getting to the point where you're like, "Oh, well, we don't have to pay writers. We can just use artificial programs to write everything"? And that scares the hell out of me because no matter what you do, and as it argues in the book, In the Lives of Puppets, machine-made art, whether it be books, or music, or words, anything, they may be perfect but they will never have the faults that come with humanity. They will never be imperfect in the way that only humans can do. Machines, the way that we're using them now, they can never have our soul, our heart, our anger, our fury, our happiness, our rage. They can't have any of that, and it shows. If you remove humans from the equation, you will never have a human story told again.

MC: Yeah. Absolutely. And one of the things I really loved about the way you positioned In the Lives of Puppets is you definitely address that fear and that anxiety. But you also offer a tiny bit of optimism in there. So it is still a little bit open-ended. It's like, "Oh, well, there is still a tiny bit of humanity there,” but it's not the same humanity that we know today.

TK: Because it's what I wish for, that we will not forget who we are in our endeavors to go running and screaming into the future, that we remember where we come from, our place in this world, and that we don't get lost in this brave new world of machines that can do everything. Because at the end of the day, yes, technology is advancing at crazy, crazy rates, but at the same time, you cannot remove the human quality from that kind of work, especially in the arts, you know? I'm not going to speak to any other field because I know what I know because this is what I do. In the arts, you cannot replace people with machines. You can't. It's just not going to work. And so when you see all of these A.I. images popping up on Twitter and popping up on Instagram or Tumblr or whatever, and you're like, "Oh, that's a beautiful piece of art." But you know, you can tell, maybe you don't know what it is exactly, but you can tell that something is not right. Something is just a little bit off to make you uncomfortable because a person didn't make that.

MC: Yeah. And it's just always just a little tiny bit off, that you're like, "This isn't right. I don't know how it's not right. Is it the hands? Is it the fingers?”

TK: You're right. “Is it the face? Is it the way the lips move? Is it the way the skin stretches on a face?” It's a whole bunch of different things that all combine. And while In the Lives of Puppets could be a warning to that, it also, I think, to me, acknowledges the fact that it's here and it's going to be here. No matter what we do, we will never go back to where we were five, ten years ago. Never.

“Machine-made art, whether it be books, or music, or words, anything, they may be perfect but they will never have the faults that come with humanity … They can never have our soul, our heart, our anger, our fury, our happiness, our rage. They can't have any of that, and it shows.”

MC: Definitely. So, I also wanted to chat about your queer representation. You have always had such fantastic queer representation in all of your stories, and have been pretty open about how important authentic queer and neurodiverse portrayals are. It's one of the many things I love about your work. And I especially loved the asexual representation through Vic in In the Lives of Puppets. Did you always intend that the story would center on an ace relationship or did it just evolve out of the world that you built?

TK: No. From the very beginning, Vic was going to be asexual. I never saw him as anything but being asexual. And I am asexual. So having that kind of representation in books, coming from a place where an author understands what that means to live in that kind of world and be asexual, that's important to me because we don't get to see that a lot of the times in books. You know, God love them, but sometimes authors, when they include asexual characters, they, for some reason, think that they are characters that need to be cured. That, "Oh, you just haven't met the right person yet. And, wow, look at this, now you're having sex and everything is wonderful. You're normal again." And that's not how it works. That's not who we are. We're not broken, so we don't need to be fixed. We're just different that way.

And I wanted that for In the Lives of Puppets, not only because I have a platform to be able to talk about such things, but I also wanted it to read authentically for Vic's experience because, look, when this book opens, Vic has his family, and that's it. He doesn't have anything else. He's never known fear, real fear. He's never known heartbreak. He's never known grief. He's never known anything that we kind of take for granted. So the book was wanting to explore what happens when a person, a human like that, has to experience those things for the first time.

But also, what does love look like in a place like this? Romantic love, not just familial or platonic, but what does romantic love look in a place like this, especially when someone considers themselves to be asexual? And what I love, and I'm getting a little high on my own supply here for a second, but what I love about Vic in this book in relation to his asexuality is that the other characters, the other main characters, when it is discussed, because it is discussed frequently on page, his boundaries are respected and enforced. There is nobody saying that he's broken or something is wrong with him. He's asexual. He's Vic, and he also just happens to be asexual. That's part of him. It doesn't make up his whole. It's just who he is and no one in this book tries to change that. And that is so important for me to be able to show that people like Victor, people like me, don't need to be changed. We're okay with who we are and how we are, and that should be good enough for everybody else.

MC: Exactly. And it's such an important conversation to have, because asexuality in particular feels like a part of the LGBTQIA+ community that doesn't often get the platform that it deserves. And that community, your community, we need to learn more about it. We need to respect more of it. And in addition to showing one of the ways that asexual love and romance can manifest, you also spend a lot of time talking about how asexuality itself exists on a spectrum. You can be sex-repulsed. You can be sex-positive. And I think it's a great education moment for maybe folks who don't understand what asexuality is. So, thank you for that.

TK: I wrote a book back in 2015, a contemporary romantic comedy called How to Be a Normal Person. And that was the first time I ever wrote an asexual character as a lead character. And I did that because I was coming to terms with my own asexuality, understanding what that meant. And when that book came out in 2015, and still to this day, I get messages from people saying, "I thought something was wrong with me. But it turns out that there's not. I just, I'm asexual. And that's how it is." And I've heard from people who had never heard the word asexual before, or if they had heard it, they didn't know what that meant. They thought, like a lot of people did, that it was a medical condition that meant something was wrong with you. And so being able to have these teachable moments in fiction while still being able to tell an entertaining story is, man, it's just the best job in the world.

MC: I love it so much. And speaking of some of your older work, I have personally been a fan of yours for a while now, starting with Bear, Otter, and the Kid. So, I go way back.

TK: Way back.

MC: I am definitely one of your old-school fans. So, I wanted to know how has your process as a writer evolved since that first story?

TK: Oh, boy. When I wrote that first book back in 2009, 2010, I was working 60 hours a week at a job that, if you know their lizard commercials on television, then you'd know where I worked. And I unfortunately received the worst compliment anybody could ever receive, which was I was told, "TJ, you are very good at insurance." And if you've had anybody tell you that in your life, then you know how soul crushing that could be. And I wanted to write more than anything in the world. I always have, since I was a kid, I wanted to write. So, I decided one day to sit down and write a book, not having any idea what I was doing. I didn't go to college. I have a semester of community college under my belt, and that was it for me. All I knew was my love of books and my love of writing. So I set out to write that book.

And, wow, going back to that book now is an experience, man, because it is a very evident first novel. It is imperfect in ways that I kind of cringe about now sometimes, but I also find slightly endearing because I think if you read Bear, Otter, and the Kid, my very first book, and then you pick up In the Lives of Puppets, you're going to be like, "How is this the same writer?" And it's just growth. I never want to stop learning how to be a better writer. I will never be the best writer. I will never be the world's greatest writer. But if I could become just a little bit better than I was the day before, then you know what? I'm doing okay.

And the biggest thing, though, that has changed from those early days to now is I don't write like the world is ending. I don't work 60 hours a week in a cubicle and then come home and write until two o’clock in the morning and then get up at six the next day to do it all over again. So, one, I am older. I'm about to turn 41, so everything makes me tired now. And two, I love the time I get to spend in the world now. I don't have to rush. I don't have to feel like if I don't put a book out quicker people are going to forget who I am, because that's how it feels in the indie world and the self-publishing world is that if you don't continually put out books, you will be forgotten. And that sucks, and there's some measure of truth to it. But in the last few years I have made myself slow down, take my time, and actually find enjoyment again in it. For a while, it felt like it was becoming a job, a process that I had to get from point A to point B. And now with books like Cerulean or Whispering Door, Lives of Puppets, The Extraordinaries, I can tell the stories I want to tell and take the time it takes to tell them without worrying about, "Oh, I have to get this book out now or people aren't going to remember me." I spend more time in these worlds, and I think I'm better off for it.

MC: And you really do lean into the magic of these worlds. So, I wanted to ask, since some of your more recent books have been a little bit more fantastical than your old-school books, which were a little bit more grounded in reality, has your approach to world-building changed at all?

TK: Absolutely. Back in the day, I used to be a by-the-seat-of-my-pants writer, meaning, I would just put my fingers on the keyboard and see what would happen, and go from there. "What do you mean I totally went against what I wrote four chapters before in this chapter and broke my own rules? It's fine, it's fine, and we'll fix it in editing." But I stopped doing that because you can't plot that way very well. You kind of have to have a road map. It doesn't need to be set in stone, but it needs to guide you.

So now every book I write, every single book, before I even begin to put a word down on a page in the story itself, I write outlines, and I'm not talking 1,000-word outlines. Like, In the Lives of Puppets, the outline for that, including all of the research I did and everything that I wanted to include in this story, is probably about 50,000 words itself. That's how my outlines are getting these days. I'm getting so involved in creating these worlds that I put in things that will never make it into the book, just so I know this world. Like, Vic's birthday. I know that. It doesn't matter to the book itself, but I know that. I know his favorite foods. I know what kind of bad dreams he has. I know what clothes he likes to wear the best. Is that important to the story? No. But I know that because I want to be as in this world as I could possibly be. And the best way for me to do that is to dive head first and explore this world before I actually start writing the story I want to tell.

So, world-building to me is one of the most important things, because even if the world is fantastical, even if it is a mysterious force with houses in trees surrounded by machines, I still want it to feel real. I still want it to feel like these people, these beings could exist. I want people to feel the crunch of leaves in the forest. I want them to smell the trees. I want them to hear the birds. I want these books to be sensory experiences so that adds flavor to the world itself. Because if a world feels lived in, people can find themselves living there when they read.

MC: And I can say you absolutely nail it because it feels so real. And I think you have such a way with dialogue, banter, and character interaction in general. I mean, that's going back to Bear, Otter, and the Kid, you've always excelled at that. And it not only feels real in In the Lives of Puppets, but it also pulls on your heartstrings in the best possible way. Like, you just, you feel everything. So how do you go about creating all of those characters and mapping out those interactions in those massive outlines that you're now working on?

TK: So, the outlines are divided into sections. Section One will be like, "This is what the forest will be like. This is what the light looks like when it comes through the trees and dappling on the floor” and everything like that. But I also have sections for each individual character. In the Lives of Puppets exists because of capitalism. And I'm sorry to say this, but the reason this entire book exists was because I bought a Roomba vacuum. And I bought this Roomba vacuum for my house because I was like, "Oh, I hate sweeping, I hate vacuuming, so why not get a little machine that does it?"

And of course, being me, I put googly eyes on it before I turned it on. And then I turned it on. And when you first get one of these vacuums, what they do is they go around your house mapping out the house so they know where to go. My little vacuum—his name is Hank, by the way. He's very much a Hank—one of the very first things he did was got himself stuck in a corner. And he made this really weird, sad beeping sound. Like, it was sad that he was stuck in a corner—and this has never happened to me before and I don't know if it'll ever happen again—but when I heard that beep, seeing those little googly eyes shaking on top, this little thing stuck in the corner not able to get out, not understanding that all it needed to do was turn around and it'll be free and everything is wonderful, for some reason, that moment exploded into this entire story. This book exists because my Roomba vacuum got caught in a corner and made a sad beeping sound.

From that, I knew Rambo. And I knew Rambo would be this socially anxious vacuum cleaner who basically was a sentient version of a golden retriever. That's what they are. He has the heart and soul of a golden retriever. And from there, I was like, "Okay, what if he is acting as the Jiminy Cricket, the talking cricket, from the conscience, from Collodi's story, from the Disney movie." And then I thought, "Well, you can't just have the good. You have to have the devil too. You have to have the more human, animalistic side." So there came the nursing machine, Nurse Ratched, which stands for registered automaton to care, heal, educate and drill, and she is a sociopath. But she represents one side of Victor's conscience. You have the id and you have the ego. You have these two characters, Rambo and Nurse Ratched, who are on almost every single page—they are as main a character as Victor is—and they act as his conscience. They act as his devil and his angel on his shoulder.

And their interactions, Nurse Ratched and Rambo, to me, are, I don't want to say the heart and soul of the book, but they are certainly, to me, the best parts of the book. Because writing them, especially writing Nurse Ratched, was some of the most fun that I've ever had with characters, because you know when you meet Nurse Ratched, you see she's one type of way. But her character arc, much like Victor's, much like Hap's, much like Rambo has a character arc, they all have these character arcs where they are not the same as they started as they are at the end. And I love that we get to see this growth in Nurse Ratched, who, when we first meet her, randomly murders a squirrel. That's just who she is. That's her thing. But by the very end, you see that she is so much more than she is first portrayed. And I love that I get to put these weird two characters in this serious story about what is humanity, because you need that levity. You need those moments of lightness in all the darkness. And I can't think of two better people to accompany Vic on a journey, two better beings, than Nurse Ratched and Rambo.

MC: Yeah. I absolutely loved all of their interactions, just the banter, their back-and-forth. It was perfect.

TK: Because that's how I think that machines, if machines are aping us, if the goal is to have machines be so dissimilar from humans that you couldn't really tell the difference. Of course, in that they would sound like us. Of course, that they would talk like we do. And so Nurse Ratched, while she is still the utmost professional, sometimes devolves into her sociopathy, and the results are very interesting with what she says.

MC: Definitely. And speaking of the way these characters sound, while your writing alone was incredible, I think narrator Daniel Henning did a fantastic job giving each of the characters different voices and personalities within his performance. He's a narrator you've worked with before too. Did you already have him in mind while you were writing this one?

TK: Daniel Henning did The House in the Cerulean Sea, and he was nominated for an Audie Award for that, which is amazing, that his work was recognized on such a big level. Because when I think of the gremlins and their dads from The House in the Cerulean Sea now, all I can hear is him. That he is these voices of these characters. I was not considering any narrator when I was writing this book. It was not until it came time to actually choose a narrator that I decided to have all three of my narrators audition. I used Kirt Graves for many books. He's done the Green Creek series. He did, recently, Under the Whispering Door. He is doing the rerelease audio for The Bones Beneath My Skin. Michael Lesley, I've worked with for many years. He's done many books of mine, most recently The Extraordinaries trilogy. And then there's Daniel. So, I was like, "Okay, let them fight, so get auditions and everything." But I heard Daniel, and it's the weirdest thing. When I was listening to Daniel's audition for The House in the Cerulean Sea way back in the day, I chose him because of his voice that he did for Chauncey. It was perfect. It was the most perfect voice for a green little blobby-boy octopus kind of Jello-boy. He sounded just like I pictured Chauncey.

And then Daniel did the audition for In the Lives of Puppets. And I was like, "Okay. This is good." And then maybe 10 seconds into it, Nurse Ratched speaks for the first time, and I was sold, immediately. His Nurse Ratched voice was exactly how I wanted it to be, exactly how it sounded in my head. And I knew then that if you could get Nurse Ratched, if you could get that character, who is a very different, difficult character to actually portray, then the rest is golden. So he is the narrator for this book because of a one-sentence line that he read for Nurse Ratched.

MC: Oh, I love it. I mean, like you said, all of your narrators have just been rock stars. They always knock it out of the park. But I think Daniel Henning for this one in particular, it's chef’s kiss perfect.

TK: Right. Like The House in the Cerulean Sea, In the Lives of Puppets has a theatricality to it. It has very larger-than-life characters. Under the Whispering Door was more grounded, because it had to be. Yes, it was a story about ghosts in a tea shop, but it was also a story about grief. The central beating heart about that story was grief. So I wanted somebody like Kirt to be able to do that story. But I like to think of Cerulean Sea and Puppets as kind of bookends to each other. And having Daniel do these voices with his bevy of original voices that he can do—because while there are four or arguably five central main characters, there are a bunch of other characters that go into this book and each one has to sound different than the others, even if they're only on page for a paragraph or two. There'll never be a time when you'll hear me say, "I do not trust Daniel Henning to do right by my characters." Because I didn't even need to give him really any feedback, and this is what he did. This is what he did. He's that good.

MC: That's fantastic. I was actually curious if you had been super involved in the process of creating the voices.

TK: No. I might have some notes. I think I actually gave a note from the same audition to Daniel about Vic needing to sound a little bit quieter. He needs to be a bit more introspective. And that's probably the only note I really gave, and the reason for it is because if I am hiring you to do a job on an audiobook, then I want to be able to trust you to make the story yours. I wrote the book. This is my story. But when you perform the narration, it also becomes your story. And I want you to be able to put your own spin on it, how you think these characters will be, sound, act, how you think the narration should go with as little interference on my end as possible. Because yes, there's an argument that can be made that collaborative efforts are amazing. But with this, writing is such a solitary journey, and recording an audiobook can be a solitary journey. So I just love the idea of my narrators getting a story, minimal notes from me, and then making it their own. And it has worked out every time, so fingers crossed.

MC: Yeah. It has worked without fail up to this point. I'm sure it will continue to work because it's just always perfect. Are you much of an audio listener yourself?

TK: Absolutely. I am out in the world a lot. Not as in traveling for book stuff, although there is that too. I just don't like to be cooped up in my house all the time because I work from home, I write from home, and, yes, I'm a homebody and there's no place I'd rather be than home. But I love going out into the world. I love being in nature. I love going exploring. And so when I am out in the world, I'm either listening to podcasts or I'm listening to audiobooks. I just recently finished listening probably for the—I don't even want to say how many times, because it's probably too embarrassing—but one of my favorite nonfiction writers is David Grann, and he has a new book coming out in a few weeks. And so I went back and relistened to The Lost City of Z, which is one of my favorite nonfiction books of all time. It is the quintessential armchair adventurer book because you don't have go into the dangers of the Amazon and see the worms that go under your skin that you have to pull out, you can just read about it instead. And I am so looking forward to David's new book when that comes out because he is, in my opinion, one of, if not the best nonfiction writers working today.

MC: I'm going to have to put that on my list of what to listen to next.

TK: It is so good. And he wrote the big bestseller Flowers of the Killer Moon. That is being turned into a Scorsese movie with Leonardo DiCaprio and Brendan Fraser and all of these people, and he's just a tremendous author, and his audiobooks are exceptional.

“Books are uniquely portable magic that allows us to escape and allows us to see the world a little bit differently. And if you are taking away those books from the people who need them most, you are not only harming them, you are harming the greater world.”

MC: I love it. So can you also give us a taste of what you're working on next? Are we going to see more from Vic and Hap maybe?

TK: I can say without a doubt that In the Lives of Puppets is a standalone book, and it will always be a standalone book. For me, it would be like going back to writing another book in Under the Whispering Door, a sequel to that. I just don't see the point, the purpose. I told the story I wanted to tell. And I feel going back to the world of In the Lives of Puppets, especially with the ending that I worked so hard on—that last chapter of this book, the last pages are something I wrote and rewrote and reworked constantly. And now, in my opinion, the last chapter of In the Lives of Puppets contains some of the best writing that I have ever done. I love this ending so, so much because it's a truthful ending. It shows that not everything can be tied up in a pretty bow. And what do you do with that?

And I love the idea of closing this book and letting them live their lives without me looking in on them. I don't know what they'll do. I know they'll be successful even if there's bumps in the road, but that's a story that I don't need to tell. And the same with Under the Whispering Door, going back to that world, I worried that it would dilute the message that I had about grief and the power of humanity. I don't need to do that. House in the Cerulean Sea, who knows? Maybe one day. We'll have to wait and see what goes there. But right now I am planning on doing something a little different. I want to throw my hat into the ring for queer horror, and see what happens if I would write a horror novel.

MC: Oh, cool.

TK: Horror is my favorite genre. I read it constantly; I watch it; I play video games; I listen to podcasts that are horror stories. I love horror, and I think I have a story about a haunted house that has never been done before. So we'll see what happens with that. I am, with hope, halfway through my life. So guess what? The next 40 years, I'm going to be telling every story that I possibly can in a way that I want to tell the stories, and we'll see what comes of it.

MC: I cannot wait. I'm so excited for everything you're going to be working on in the future. And I have to say, I agree. I really love where In the Lives of Puppets ended up. I think it's such a powerful, perfect ending for Vic and Hap.

TK: Thank you. I am so proud of how this story turned out, but nothing more so than the ending. A book like this has to have an ending that resonates. It has to stick the landing. Because if it doesn't, everything that came before it will be colored a little less brighter. And so with this ending, I wanted to give my readers an ending that they haven't quite seen from me before. But also, to show that humanity, no matter what, cannot and will not be denied.

MC: Yeah. And I also love the outlook. Like, they're good in their own story. You don't need to interfere. They're going to work it out, they're going to have great lives in their own right.

TK: Right.

MC: Well, TJ, I think that's all of the questions I have for you today, but is there anything else you want to chat about before we go?

TK: Yeah. One last thing I want to say, if it's all right.

MC: Sure, of course.

TK: The world right now, and I'm going to only speak for the United States, is in a very scary and difficult place. We are seeing more and more books being banned and challenged. And I want to make it very clear to those who may only have outside knowledge of what this is entailing. These book bans that you're finding across the country right now are about two things: books by Black people and books by queer people. They are trying to take away the stories that Black people are telling and queer people are telling, simply for being about being Black and being queer. That is the reason these books are being challenged. It's never been about protecting the children or what they say. It is about control. It is about marginalizing. It is about taking away from the people who might need them most, the books that tell our stories. Last year, or maybe it was even 2021, the American Library Association released the top 10 banned and challenged books for the previous six, seven, eight months. Every single book on there was LGBTQIA-related, every single book. Two of those books were also about the Black experience. That shows you all you need to know.

Teachers, librarians, booksellers, all of these people right now are at the front line of a culture war that they should not have to be fighting. We owe them our support, especially teachers and librarians who are facing irrational communities, who are accusing them of very dark things. Books are for everyone. Books are uniquely portable magic that allows us to escape and allows us to see the world a little bit differently. And if you are taking away those books from the people who need them most, you are not only harming them, you are harming the greater world. We should be so concerned with this movement and doing everything in our power to make sure that the right to have access to books is protected, and not only that, it is celebrated.

MC: Exactly.

TK: And that's all I had to say.

MC: I agree. And I think, to your point, we also have to thank writers like yourself who are telling these stories and writing these representations and just putting them out in the world. Because without writers like you, we wouldn't have those stories to begin with. So thank you for writing and telling those stories.

TK: Thank you very much. It keeps me from going crazy, so that's why I do what I do.

MC: Awesome. Thank you so much for diving into your work with us, TJ. I had such a wonderful time.

TK: Thank you so much for having me. I'm very, very excited for people to get their hands on In the Lives of Puppets.

MC: And listeners, you can find TJ's latest, In the Lives of Puppets, on Audible now.