Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

Note: This interview contains spoilers for The Nigerwife

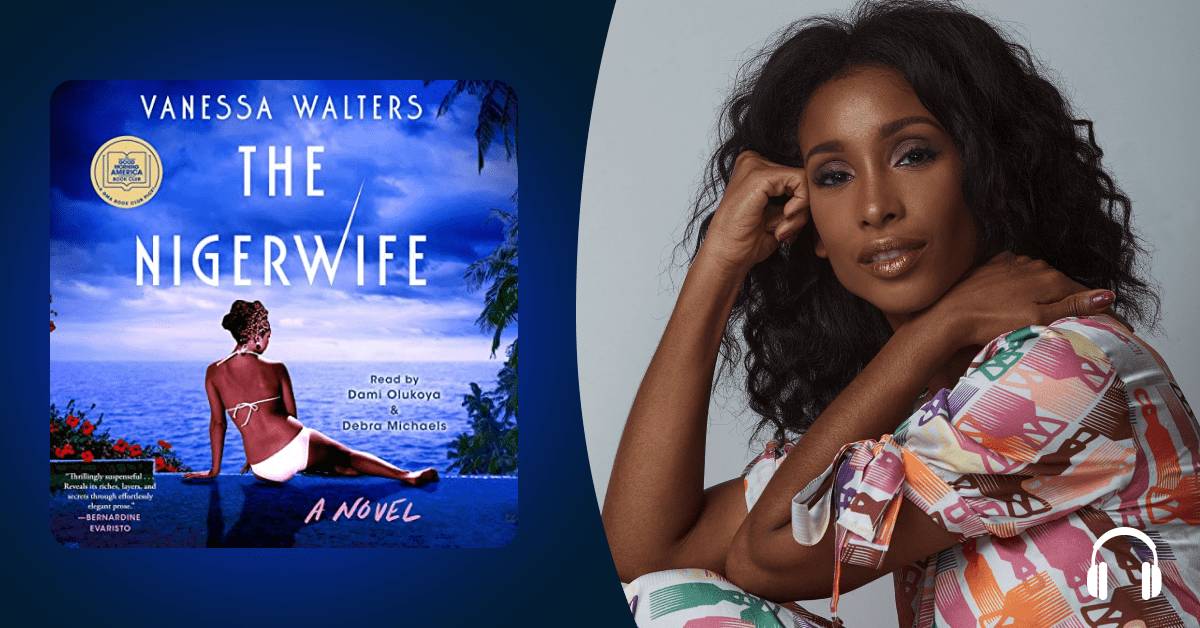

Margaret Hargrove: Hi, I'm Audible Editor Margaret Hargrove, and I'm so excited to be speaking with author Vanessa Walters about her debut adult novel, The Nigerwife. It's a riveting thriller about a wealthy young mother named Nicole who disappears without a trace, and the aunt who will stop at nothing to find her. Set in Lagos, Nigeria, The Nigerwife transports listeners into a world that most of us have never seen before and will have you on the edge of your seat until the shocking ending. Thank you so much for being here, Vanessa.

Vanessa Walters: Thank you for having me, Margaret. This is so exciting.

MH: You have written a really extraordinary novel. I listened to The Nigerwife when it came out in May and loved it so much. I recommended it to everyone I know. My sister is actually listening to it now, and when I told her I was interviewing you, she's like, "Oh, I need to hurry up and get to the ending." I actually relistened to it this week to prepare for our interview. And I have to say I loved it even more the second time around.

VW: That's so wonderful to hear, and I've had such an amazing reaction since it came out. I'm just so pleased the way it's been received so far and what people are taking from it.

MH: In the author's note, you say that the inspiration for this story came from your own experience as a Niger wife. Can you explain to listeners who may not know, what is a Niger wife?

VW: I know this is one of the thorny questions, right? A Niger wife is basically a Nigerian immigration term for the foreign wife of a Nigerian man resident in Nigeria. So, anyone who comes to Nigeria as a foreign wife of a Nigerian man living in Nigeria will be termed a Niger wife. We come from all over the world—it's sort of irrespective of where you are from or your background. As soon as you are the foreign wife of a Nigerian man living in Nigeria, you are a Niger wife.

"I think every Niger wife has a sort of existential crisis in a way like, 'How important am I to this community? How important am I to this family that I've assimilated into, but I'm not really from? I'm investing a whole life in a place. Does this place appreciate that investment?'"

MH: I read in your bio that you now live in Brooklyn, but do you still keep in touch with the Niger wives’ community in Lagos? What's been their response to the book?

VW: Yes, I do because I was in Lagos for over seven years. The Niger wives have an association, called The Niger Wives Association, actually, as it is in the book. And within that association, Niger wives provide support to each other and form committees and have events and get to know each other. In Nigeria, family is so important, and most Niger wives will not have family in Nigeria or close by Nigeria at all. So, The Niger Wives Association provides Niger wives with family. In fact, the motto is “Sisters All.” Some of those women are still family to me, more like family than friends in a way, because they're across the age spectrum. And so, I have the aunties who still check in on me and want to talk, and they've been so excited about everything that they've seen happen with the book.

They've been incredibly supportive, and that makes me so happy because it's something I was quite nervous about. Obviously, I'm just writing a great book, right? And it incorporates the Niger wives experience. But I have been aware that some Niger wives may feel put under the spotlight because it is called The Nigerwife, and also some may have felt, you know, am I trying to say something about an experience which has shared elements? But obviously, it's very different for every individual and depending on where you are from and what your time in Nigeria is like.

So, there was that nervousness going into the whole promotion of the book. Will they feel I've represented the Niger wives experience in a way that is fair? In a way that they feel they can relate to, in a way that they can get behind? And I've been so, so pleasantly surprised and relieved to see how much they've enjoyed it for what it is, which is a great story. But also, they feel that I have captured that shared part of the Niger wife experience in a way that's very authentic, and they've been very touched by it actually. I think [it captures] things which when I was writing about that I didn't necessarily even recognize as a Niger wife experience, like the cultural isolation and when things go wrong, that fear of like, you know, who do I turn to? Of the difficulties, even perhaps in the sort of opening up to other Niger wives—everyone's got their own private struggles. I think they could all relate to it so much so that they've actually said they're going to use the book as a sort of a discussion text in a way that can make The Niger Wives an even stronger organization going forward. So, that has moved me and has been quite important to me, even though that's very separate from, “Is this a fun book to read? Is this a well-written book? Is this a thrilling novel? Is this something tons of other people who have no idea about Lagos or the Niger wives can enjoy?”

MH: Great. That's great to hear. So, in The Nigerwife, Nicole seemingly has the perfect life. She has a handsome husband, a beautiful home, a glamorous group of friends. But when Nicole goes missing, the cracks in her so-called perfect life start to show. Her estranged Aunt Claudine, who raised her back in London, travels to Lagos, determined to find her. It's such a compelling story with a lot of twists, surprises, and shocking revelations along the way. I'm curious as to why you decided to tell Nicole's story as a thriller.

VW: Well, I think it just developed that way because Lagos is such a melodramatic city. it's a city of extremes. It's a city that is very showy and where people are very effusive. And I feel like that just operated on me as a writer in a way to tell a very dramatic story. I think also some of the questions that I had about my experience in Lagos were sort of on the thriller side of things. For example, I lived on a compound where, occasionally, dead bodies would float by the house. So, that scene in the prologue when Nicole is looking out and seeing a dead body—that actually happened to me. That feeling that she has about the body was my feeling, actually, and I really felt like the body ended up being a metaphor for so much in the book. What happens to a body says so much about society; it says so much about what we've been through in life. That was just such a big question for me, and it made such an important entrance into The Nigerwife.

Also, a feeling I had at times, which I could only write about, and I wrote about it in this fictional way—the feeling that Nicole has of having sort of disappeared in her life or sort of being invisible. From there, it was a short jump to say, what if a character really disappeared? Would people even notice? Of course, they would sort of notice, but what would be their reaction? So, I think every Niger wife has a sort of existential crisis in a way, like, "How important am I to this community? How important am I to this family that I've assimilated into but I'm not really from? I'm investing a whole life in a place. Does this place appreciate that investment?" And I think for Nicole, she has all these questions, and they became literal questions very easily, and that's how it became a thriller.

MH: It's interesting you say that Lagos is melodramatic because it almost feels like Lagos is a character in the book. You've created such a vivid picture of what it's like to live there and, as you mentioned, the huge disparity between the haves and the have-nots. Can you talk a little bit more about your experience living in Lagos? I'm curious if a lot of the places and street names that are referenced in The Nigerwife, are those actual places in Nigeria?

VW: Yeah, I kept it very close, actually to the point that I set it in 2014, which is a time when I was there so I could remember where everything was. Some names have been changed for legal reasons, but essentially the geography of the place is the same as when I was there. So, the places they go, the streets—yes, they are the same. I had wanted to keep things very close for a couple of reasons. One was because I started writing this in Nigeria, but I left Nigeria in 2018 and, at that time, perhaps I'd written maybe 30,000 words. So, I still had another 60,000 words to go, and I was not able to go back to Nigeria to check new places out or say, "Okay, if I change this, you know, to keep that like for..." So, keeping things almost as a snapshot just made things much easier to write. And even though it's fiction, [I wanted the story] to sit in a certain truth of the place, in a certain time period. That's why I deliberately kept so many things the same.

MH: It’s very vivid. It feels almost like you're there when you're listening to the book. So, speaking of listening, let's talk a little bit about the narration. You have two really great, accomplished narrators—Dami Olukoya voices Nicole, and Debra Michaels voices Aunt Claudine. The novel also has a really interesting structure, where chapters alternate between Nicole and Aunt Claudine as we learn about the months prior to Nicole's disappearance and Claudine’s search for her in present day. Did you envision having two narrators for the audiobook as you were writing it?

VW: I started with only Nicole's point of view, but I really wrote this novel out of questions. And so, the question of “Who is Nicole?” just sort of got bigger and bigger and bigger. And maybe it's just the way I write—I don’t know if it's a common thing—but it's like the questions become characters, the questions become places. Who is this character? Where is she from? What was her life like? Who comes looking for Nicole? Who would care about Nicole the most in this story that I'm telling? Those questions created Claudine as a character. As an author, how would I answer those questions about cultural differences and identity best? Have somebody [from outside of Nigeria] come in. Because, don't forget, Nicole was living in Nigeria for some years before she disappeared. So, have someone come in who's never been to Lagos, who knows nothing about Nigerian culture, really, to ask those questions, to kind of reveal the culture, and Nicole's culture as well, in a way that just makes it very interesting—a very interesting exploration of this cultural difference and what it means for us when we experience that.

"I was trying to really answer bigger questions about culture and history and how it travels down through generations. And how are we impacted by things that happened to our ancestors that we are not aware of."

MH: Have you had a chance to listen to the audiobook?

VW: Yeah, I have. And honestly, I am just amazed. It's so fun to listen to. I love Debra's voice. I love Dami's voice also. What I love about it the most, from my perspective [as an author], is that I can hear so much more with their narration. I can hear all the things that maybe I was trying to do on the page. I can hear it in their voice more. I just feel so thrilled to hear the way they highlight things I was trying to do on the page that maybe you see so much on the page. I don’t know if you can understand what I mean, but they bring it out in all its glory, whatever I was trying to do. And it's wonderful.

MH: Definitely. I love the narration. It sounds so authentic. So, speaking about Aunt Claudine's character, I find her to be someone who is really ruled by duty and responsibility. She raised Nicole after Nicole's mother died of a drug overdose. Claudine herself has an ill mother at home in London, yet she travels to Lagos to find Nicole. And later in the story, we learn, in another surprising way, that Claudine has always been, as she says, "The only one prepared to do what needed to be done." You said that Claudine's character came out of questions you had, but she feels so real. Is she based on any real aunt or family member in your life?

VW: I think she's an amalgamation. She's an amalgamation of different elements of older Caribbean womanhood and Caribbean, or I'd say, Jamaican, history that I felt were important for me to explore. I definitely had to ask my mother a lot of questions writing Claudine's character. There were elements of my mother's experience that I felt are very widely shared by her generation, but not really spoken about enough, which is, what was the impact of being what we call a barrel child? What was the impact of Jamaica's more recent history, after slavery, where basically Jamaicans still have a pattern of migration, where they have to leave the island often to find work? How did that impact families? How does that impact the way we think of family? You know, being Jamaican myself, I was really trying to answer those questions.

And so, I drew in different elements from my mother to my aunt to my grandmother. I have two Jamaican parents, so on both sides, I have these Jamaican women, and I did a lot of research as well. I read books by Erna Brodber, who's written extensively about Jamaican history and Jamaican experience. I really wanted to understand certain elements about Jamaican culture, which I felt were sometimes troubling but sometimes to be celebrated also. For example, Jamaican households feel more matriarchal. They can feel more free, in a sense. They can feel like there aren't these rigid power structures that you can find in other cultures, not just Nigerian culture.

I really wanted to explore these things, turn them on their head, look at them. So yes, I would say my family inspired a lot of those questions, but definitely I was thinking bigger than any one person that I know. I was trying to really answer bigger questions about culture and history and how it travels down through generations. And how are we impacted by things that happened to our ancestors that we are not aware of, that we are still reacting to—things that happened like three generations ago. You know?

MH: What do you admire most in Aunt Claudine?

VW: Hmm, lots of things. There is a sense of adventure in Claudine, which I can totally relate to myself. Claudine is a little like, “This sounds terrifying, but I could do it anyway.” And I think it does come from this pattern of migration, you know, and also something which is a part of Jamaican legacy—a self-determination, deciding something for yourself without needing to read it in a textbook, without it needing to be validated. Perhaps it's difficult to articulate, but it goes back to Marcus Garvey. His sense of “emancipate yourself from mental slavery,” determine things for yourself. There's a knowing that we all have, right? And this is what is pushing Claudine forward at every stage. So, something that I find most inspiring about Claudine is that she can be in a place where she doesn't belong. She can be in a place where she's looked down on, she can feel threatened, but there's something in her—a sense of herself and a sense of determining value for herself—that just keeps pushing her forward to the next thing and the next thing. And it's so interesting to see how she makes all these decisions in the book.

MH: Definitely, she's very brave—she definitely is. I'd like to talk a little bit about the ending, because when I first listened to the final chapter, I had to immediately go back and relisten because I was like, "No, that didn't just happen." So, for anyone who has not listened to The Nigerwife yet, here's your warning that there are spoilers ahead. We find out in the final chapter that Nicole is alive, and she has washed up in a small village down river, but she has amnesia and she doesn't know who she is. After seeing her struggles with identity, isolation, and a feeling of belonging, does your ending feel like an opportunity for her to have a fresh start, a new beginning to maybe become someone new?

VW: Oh, oh, yes, for sure. I played around with different endings, and I felt like that ending was the most authentic ending to why I wrote the book—which was not to give answers but to explore questions, and questions just lead to more questions. And honestly, I feel like the ending really resonated from me as in she's picked up by the people who, ultimately, recycled the trash that's left on the beaches. These are the villagers who live on the little islands. And she herself was sort of discarded in a way by the people in her life—it was easier for them to just let it go because she was an inconvenient truth, as it were, that was now derailing the family fortune. But the thing with the trash, and it's the thing I used to think of when I used to see the trash float past, is this—it never really goes away. These memories that we discard, they never really go away. So, Nicole hasn't gone away either. She's washed up on a beach, figuratively, right? And now, a new life begins, but we don't know what that life is going to be or what form it's going to take. I felt like that was the most authentic way for me to end the book. I know it's been quite controversial, but honestly, it comes from an authentic place.

MH: Got it. The Nigerwife was Good Morning America's book club pick for May, and I've seen it on countless lists of must-listens for summer. So, after a career in international journalism, playwriting, and you've also written several YA books, how does it feel to have your debut adult novel garner so much praise and attention?

VW: Oh, well, it's beyond words. It's beyond a dream. When I was in Nigeria, I hardly wrote at all—at times, I forgot that I was a writer, or I resisted that I was a writer. And my writer friends would sometime message me and say, "Remember, you're still a writer. You are supposed to be writing." And I felt like I'd drifted so far away from that path and to come back to it in such an amazing way. To come to New York, one of the most competitive cities on Earth, and to get someone interested in a book that has nothing to do with New York, has nothing really to do with America, was totally shocking for me to start with. To have Atria Books come along and love this book so much, and my editor to be totally obsessed with the book, was something I never expected. Not to talk of a deal with HBO, right? I mean, that was not in my thinking at all. That was totally unexpected, and I'm so grateful for that. And then GMA has been like the cherry on top of the cake. To be so embraced by America and to have so many people know about this book and to see so much love on the internet from people reading has just been really crazy. You know, if I had envisaged stuff like that, I would've written a completely different book to be honest. Even the title The Nigerwife, I just kept saying, "Do you think people are really gonna get this? You know, it's too unfamiliar." But I have been really just amazed. I'm so grateful to have had such a positive reaction to the book, and I hope it continues.

MH: Well, you mentioned HBO. So, they have scooped up the rights to turn The Nigerwife into a limited series helmed by Amy Aniobi, who was a writer and director on Insecure, which is one of my favorite shows. What has been the process behind the scenes of the series?

VW: I think the first process has been finding the main writer for the show. They talk to a lot of different writers, and I think one of the biggest decisions for the show is which writer. So, it's something they don't rush. They have gotten to a point now where they've selected the writer. Obviously, there's a writer strike going on at the moment, so all tools have been downed for now. But I think that part of the process, and that's like one of the biggest parts of the process, has been dealt with.

I have to say, like you, I was such a fan of Insecure. I feel like I grew up on that show in a lot of ways, because it totally changed my feeling of being seen as a Black woman and in terms of the conversations we can have. The show is serious and it's silly, and it shows that we can really communicate about ourselves and with ourselves in so many different ways. And that totally inspired me when writing this novel—that I don't have to be afraid of how I communicate certain things because I'm not necessarily gonna get everything right. A writer isn't there to get everything right, but a writer should feel free to tell the story they want to tell. And that's what that show actually gave me.

MH: I think it'll be in great hands with Amy. I'm excited to see what she does with it. So, I read a recent tweet that you say you have a title and a storyline in mind for a potential sequel for The Nigerwife. Can you share any details about it? What would happen in a sequel, not to give the entire story away?

VW: Well, I just have some ideas. It's not a definite storyline. But, one thing which I really like about Lagos is the rainy season, and it does feature in the novel and how apocalyptic it feels. And everything just feels heightened during the rainy season because the rain, it comes down in sheets and it's so loud. it's partly because of how the roofs are made. It's sort of deafening when it comes down, and it just feels so apocalyptic in nature. It just makes me want to write a sort of apocalyptic environment or an apocalyptic potential setting, with this Oruwari family again in that and seeing what's changed for them over the passage of time and seeing how Nicole fits into this story.

But again, I think it's very inspired by Lagos as a character and also how things might have changed since the time period in which The Nigerwife is set. So actually, I'm going to Lagos again this year, and I'm gonna get more ideas. But I think this idea of family is really compelling, right? Because family is at the heart of how we feel anchored in this world, and so, as a society, as people, we’re always obsessed by this idea of family. That's often why a lot of the most successful shows have been about families. You look at Succession, which we just had; you look at Game of Thrones—it’s these family dramas but playing out in a way that has bigger consequences for society, and, in terms of what we take from it, how it changes our idea about who we can be in this world. So yeah, family, environmental disaster, and our characters, Tonye, Nicole, and maybe even Elias. Let's see what Lagos has made of him over the subsequent years.

MH: Well, I would definitely listen to it. Thank you, Vanessa. It was such a pleasure talking to you today. The Nigerwife is one of my favorite audiobooks of the year, and I'm so happy for your success. I can't wait to see The Nigerwife on my TV screen, hopefully very soon. Listeners, The Nigerwife is available now on Audible.