Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

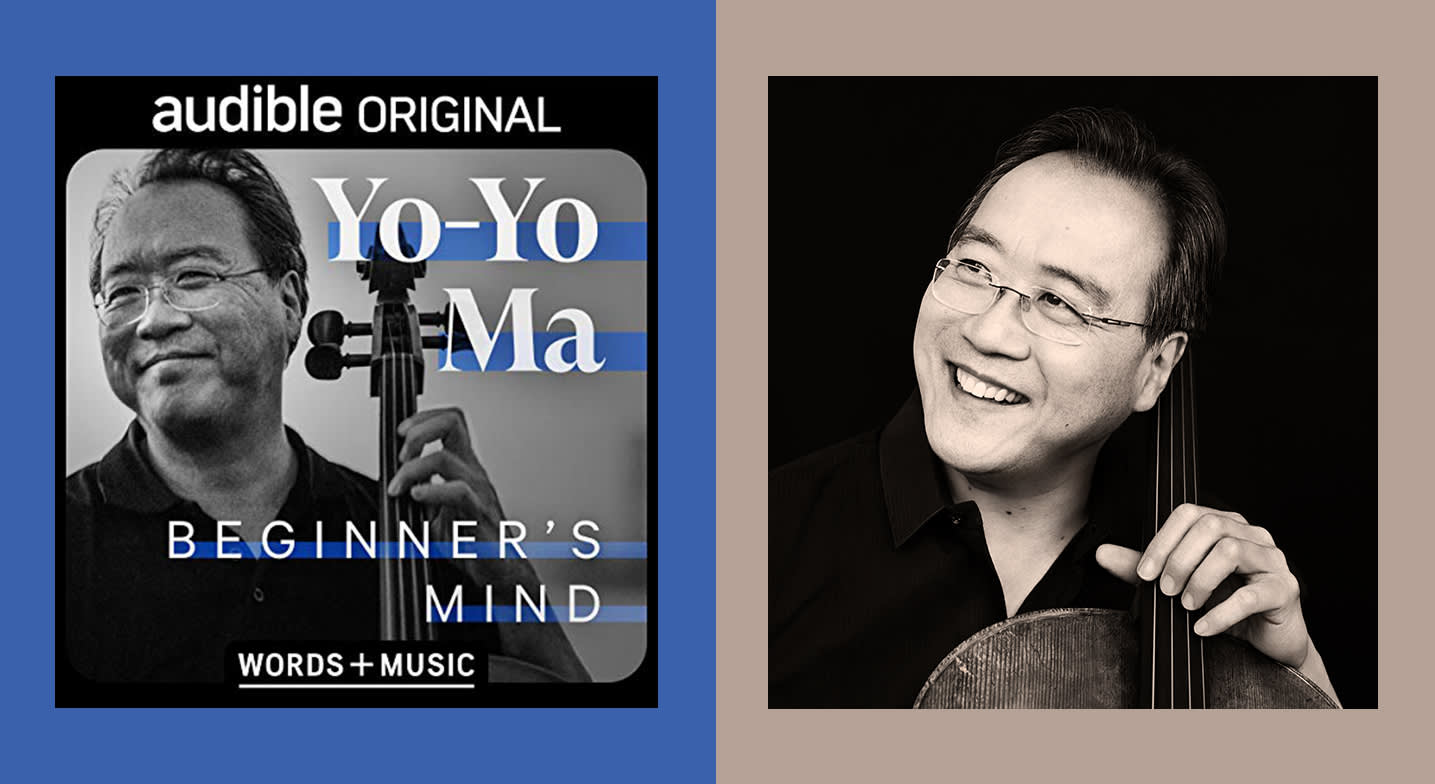

Vanessa Harris: Hi, I'm Vanessa Harris, and today I'm talking to Yo-Yo Ma. Yo-Yo has been a unique American cultural icon for decades and I am thrilled to have him with us here today to talk about his new Words + Music Audible Original, Beginner's Mind.

For me growing up as a young classical musician, you were just always there and inspiring and a peaceful presence of greatness, but our listeners likely know you as the remarkable American cellist who performs at critical national moments like the broadcast of the hundredth anniversary of the Statue of Liberty or at the first anniversary of 9/11, or maybe listeners have seen you on an incredible number of TV shows, from Sesame Street to Mr. Rogers to The Colbert Report to The Simpsons. Welcome, Yo-Yo.

Yo-Yo Ma: Thank you, Vanessa. It's great to… I'm glad I'm an icon. I'm not sure what that means. Is that an object?

VH: Well, for me it means larger-than-life personality. A person that's always been in my ecosystem for sure. You know, [when I was] growing up as a young classical musician, you were just always a part of my life.

YYM: Well, that's partly because I'm old and, let's see, I'm 65 and I think if I reach 75, I then truly qualify for being an antique.

All aside, I have to tell you, I've so enjoyed the process of doing this audiobook. It actually made me think a lot about things, which of course already the pandemic is making everybody rethink lots of things. But for me it was an opportunity to look into a pretty fast-paced life, where I've spent most of my time away from home for many, many decades. And to be able to actually take a step back, it felt as if I were on an enforced sabbatical, right? Because on a sabbatical you can think about things, you can…find [time] to retread all kinds of things. The Audible book gave me the discipline to say, “Okay, well I gotta deliver something.” But what I'm delivering are things that I should really be working on to assess and to evaluate, and in order to move forward, let's look at what happened and what does that mean in terms of moving forward?

"Writing the Audible book made me aware of what the questions I was asking myself throughout my life were and what I was actually contending against."

VH: Can you talk a little bit about that process in specific, like what you were thinking or, as you were pulling it together, what really popped and felt important to stress?

YYM: Sure. Well, I can tell you that I first heard James Taylor's Audible book and I loved it. I just thought it was wonderful. I love hearing his voice telling his story and I thought it was a wonderful thing. What I know about my life is that I'm an immigrant, and I don't know how people view immigration, but my view of immigration within my family was that it depends how you come and what age you were.

And for me at seven, it was a new beginning versus, for example, for my older sister who was four and a half years older, she knew that she gave up a life in France, right? She had a life to give up. Whereas for me, it was like, “Hey adventure,” and so that was kind of neat.

As far as looking back, one of the things about immigration is that there was no safety net. People talk about immigrant energy. You know, you work harder because there's nothing back to fall on, right? You don't have relatives that you can go to and things fall apart and you just have to make do. You just have to push ahead. So, that's one part of it.

I think another part of it is for being a musician, there's no reason for there to be one more musician in the world. A town needs a fireman. People need doctors, there's certain professions where you know you actually need that in order for community to function. We know that, yes, we need music, but there's no need for a specific number of musicians to say, “Okay, we need one musician per thousand citizens.” Right? Yeah. So that doesn't happen.

I've always said to myself as well as to others who were asking, "Should I be a musician?" I always say, well, I give that answer and say that, therefore if you want to do music, you actually have to find the specific reason why you need to exist, right? And I came to the conclusion of saying that, well, then I'm not gonna be a musician because I can be, or just because people can hire me as a musician, but I have to make sure that I'm responding to a need. So, what is that?

For some people it's, music is food. It fulfills a need. My wife says, "It's important you go do music because I need it." So I say, “Wow, that's pretty good. That's great that you feel that way because I sometimes don't feel that way or I doubt myself." So thinking through how I got to how I think today, the way I think, why am I thinking this way? Well, I got to figure it out. And partly it goes to background, like my family background, the move to the States and my education and people I've met. One thing that the pandemic taught me is, is how grateful I am for all the people that have helped me along the way.

I've never thought that I have a life in music because I deserve it, like, “Oh, I'm good therefore I deserve it.” I don't think that way, so I think that time gave me the opportunity to go back and to sort of lay it out and say, “Okay, well, you know, when I met Manny [longtime music collaborator Emanuel Ax] and I was 15 and he was 21, and I admired him and he did all the things that I wanted to do. He was in college and he was funny. He told great stories. I wish I could tell great stories.” It deepened in a way already what was a great friendship because I could actually express that not only in an Audible book, but to him personally.

Same thing with Kathy Stott [another collaborator]…this is amazing. Serendipity brought us together and somehow… But we each sort of moved along parallel lines and we wanted to explore things and we explore things together. And you also didn't want to just say, “Okay, well, I'm gonna make my career as a pianist.” You made sure that you would be doing music in which you love on terms that you thought were acceptable to you as a human being. And I think all these friendships made me think that, yes, we actually think that we're human beings first before being a musician.

VH: I loved the anecdote that you talked about—was it Pablo Casals?—where you met him and he talked about being a human first and in line. And I was so intrigued then in the beginning, you frame the piece early on as four stories of beginnings. Quote, “a few of the departures that helped me understand my identity and responsibility as a cellist, as a musician and as a human being.” I think you hinted at a little bit in your initial answer, but I was really curious, why these specific stories, what stood out to them about you, and interestingly, why did you phrase it like that in the opposite order from the anecdote with Pablo?

YYM: Well, probably because I'm a slow learner. I first read that when I was, like, nine, and I thought, “Gee, this is perfect.” I love that order, but I had to actually go through the reverse order to get to where I am thinking the way I think today, and I think in some ways some of it is societal. Some of it is my own slow nature. The societal part, I think, comes from the fact that we went through a period, a couple of hundred years ago, look, you read Hamilton, he spoke five languages. How many politicians do we know speak five languages? Right? I mean, that was the beginning of our country.

"...You can only avoid burnout if you develop an emotional attachment to a place..."

So we moved from people who did multiple things and built the country. John Adams was a farmer, right? And I'm thinking, wait a minute, there was a time when people went and did service because it was good for the country, and people did multiple things and were not necessarily specialists.

We've moved from a generalist culture to a specialist culture. Hence, I started off as a cellist, then I become a musician and then a human being. Whereas at that time, people probably started off as human beings and said, “Well, we gotta do something. What are we gonna do? You're gonna do this. I'm gonna do that and let's figure it out." So part of that is societal. The other part is… Writing the Audible book made me aware of what the questions I was asking myself throughout my life were and what I was actually contending against, what kinds of problems I was trying to solve, trying to sort of say, why do I need to travel seven months out of the year? Which was the normal for me for 40 years.

And I never felt I was a regular person, because in my community people came home on weekends even if they worked away. I worked on weekends, I work nights. So friendships were difficult because in a way you're never available to your friends. "Can you come for dinner next week?" "I'm sorry, I'm on tour." People only ask a certain number of times before saying, “Well, they're obviously not interested.” No, we're interested, but we're not, and then we had children, and of course we just kind of went underground for years because we would rent a movie and we'd fall asleep, right, because we're tired. All the things about life happened and we were just trying to figure it out.

VH: It's so interesting to me, you bring up presidents, being generalists, going from that, to the pendulum swing of the modern era, where it's much more about specialization, it's about identity then too, right? Because I am… I work in marketing. That's what I am. And it sort of like individualizes and compartmentalizes the different parts of your life.

One of the things I love about Beginner's Mind is how you create an arc and a narrative between these four disparate times that creates the fuller picture. For people that might not know the classical music world, I loved how much texture you brought in too.

I did want to ask you a little bit about the title Beginner's Mind. For those who haven't listened yet, can you share a little bit about what you mean by the "beginner's mind"? Why would one want to cultivate it? What might let you know you're in that space?

YYM: First of all, it's something I've always held to in traveling, because when I travel, when we travel, we are probably, especially if you go to a place that you know very little about or that you don't speak the language, you don't know people's habits or whatever, you are in a way maximally stimulated. That's why often when people go do foreign traveling, after a day of listening, trying to figure out a language, you're exhausted. You can't wait to get back to your room and say, "Wait a minute, just give me a hamburger and let me just chill." Right? Because you're overstimulated.

So traveling for 40 years and going to different communities around the world, including the United States, all different parts of the States, exploring how each place is absolutely fascinating and interesting in its own way and has a distinct history in our country's development, I think of my part as being Waldo. I get dropped into different communities. "Where's Waldo?" "Well, he's in Peoria." "Where's Waldo?" "He's in Acadia National Park." "Where's Waldo?" "He's in Thomasville, Georgia." And each place is absolutely unique.

I coped with surviving a life on the road by making sure that I am never the guy in Death of a Salesman. You get burnt out, because so often people will say, well, you know where you are, it's Tuesday, you must be… Early on, I decided never, never to live that way, which meant that I spent more time finding out what's happening in, you know, in Thomasville, Georgia, or in Elkhart, Indiana, you can only avoid burnout if you develop an emotional attachment to a place, which means you got to put out, you got to care, you ask questions, you're curious. And then you find something.

The thing that people are willing to share, because people are always willing to share what they love, which is their community. And you realize, "Wow! That is precious." That's how I kind of got to "beginner's mind," because you have to actually realize that you are there without any preconceived notions of, “Oh, I'm in this place. It's a very dense or loosely populated area. What is it?" You make no decisions about a place and you just have to actually drop every preconceived notion you might have of a place. And then you discover.

You go to LA. In the beginning for an East Coaster you say, "My gosh, it's all highways, it's cars. How can you live that way?" And then you discover what a fantastic place it is and what a complex series of people and populations and demographics and whatever, and just a knowledge that's there. And it's very fashionable for any part of one country to say, "Oh, you're from that part. Yeah. You know, there's nothing." "Oh, you're Northeast liberal." Well, it's crazy. We make these funny decisions about one another that we would never make the same decision about someone living closer.

VH: Totally. And I think part of that has to do just with cognitive load, right? Like there's only so many things that you can take in, so you have to make some decisions. But to your point, what strikes me is, if you're in a new environment or a new thing, the idea that you would hold on to that in absence of evidence feels like one of the gifts actually that music can sometimes give.

At the risk of sounding trite, we've been living through historic times, quote unquote. What role do you think an artist can play during times of disruption and crisis? And related to that, what responsibility might we have to each other if we are in the arts?

YYM: I think generally people who are in the arts are trying to answer questions, but the questions are not, what's right? and what's wrong?, but more questions that involve meaning purpose, existence, and what are we here for? What is this all about? Who are we? And in terms of turmoil of which this is definitely one, those are the questions that we ask ourselves. Why us, why is this happening to us? Life was already tough, but now we've lost everything. They're not giving us a break on the rent. We may become homeless. Our business has to close because it's better for the storefront to be empty than for us to get a break and maybe be able to do that. I mean, people are coping with impossible situations and we all have a shutoff point.

There's empathy exhaustion, right? You can only read so much bad news until you, if you're reading a newspaper, you turn the page when you see the bad news, I can't take it. I have got to…or they turn the television off, you turn the radio off because I can't deal with it.

"I think the job of people who are in the arts is to be able to take the universal and make it tiny—tiny so it's right in front of us so we could suddenly cry."

So I think our job is to make sure that as we go through tough times, we don't lose our humanity. Because it's so easy. We went through 9/11 and several thousand people died. It was a national tragedy. We all felt it in the country. We were absolutely there. And somehow we dealt with it. We just lost 250 times that amount of people. I just think that, for a country that deals with statistics and metrics, that's all the statistics, more people than were lost in World War II, the Vietnam War, the Korean War, all of the wars.

But somehow many of us are inured to it. It's sort of like, "I can't take anymore. I can't, you know." It's not because people are nasty. It's just, so how do we deal with it? I have a very good friend, Peter Sellars, who's a theater director, very wise person. He said to me, he said, "Yo-Yo, if I wanna show something about the Holocaust, I don't show the numbers. I will just show a grassy knoll and let people know that underneath people are buried." And it's like, so in a way less is more. I think the job of people who are in the arts is to be able to take the universal and make it tiny—tiny so it's right in front of us so we could suddenly cry.

It's not about how beautiful my cello sound is, or what an expensive instrument it is—has nothing to do with it. It's whether the cello as an instrument of sound that could move air molecules and can touch someone's skin, which is their largest organ. And you're zooming into her hospital room for a patient who can't see any of his or her relatives that gives a moment of comfort. That is not about 540,000 people dying. It's about just that one person that you're acknowledging, because we're acknowledging each other's humanity.

It's the closest I can come to you to give, say something to you that might mean. So it could be a poet reading a poem. It could be, and there are people who have been doing this all during this time, you know, in Britain, in certain cities in our country, people bang pots and pans to celebrate health workers, that sound makes people cry because it's like, yeah, you're acknowledging my humanity. You can't say it to us in person, whatever, but I hear the sound.

In England I called Kathy Stott one day, and I said, "What's that noise in the background?" She says, "Oh, it's Thursdays. That's when they do that.” I said, "Wow, this is amazing." But then people do it in our cities too…so it's not about, oh, famous people doing stuff. It's about everybody pitching in. And they do, and that's our humanity.

VH: To your point of pitching in, in a way that is more one-to-one, like, at a certain point you cannot as a human fathom the enormity of the loss.

YYM: Right. That's right. That's right.

VH: There's just no way to get your arms around that. I speculate we’ll be grieving for many years and it'll pop up in strange ways once we're through this, but that's such a thoughtful response. Thank you.

If there's one thing you hope listeners will take away after hearing Beginner's Mind, what do you hope it will be?

YYM: I think to have the ability of being quiet. I think we live in a very, very noisy world, surrounded by so much stimulation broadcast at us. The quiet that makes us mindful of our immediate surroundings, you know. Taking another look at the light fixture or at the tree outside or listening to the birds singing at five o'clock in the morning, to the first bird and to the last bird song at twilight.

And just looking on a clear night, spending just one more minute looking at the vast universe and thinking about your grandparents or the first people from your family that arrived in the States. Just a mindfulness that's outside of our daily map of traversal going from A to B to C to D and back home, right? Every day we do that. On the weekends, we go A to H and G and Q and then go back home because that's the weekend, right? And then maybe once a year, we might go to M and N and then come back. But to actually be able to look at the whole alphabet and say, "I'm actually part of this, that actually…everything in this world between humans and nature is actually connected." And so if we lose bees, that actually affects not just the honey I can buy, but it actually affects me in some way.

To actually make those extra connections, because that's actually two things: it gives life meaning and it makes us appreciate things more. And it actually leads to maybe my turning the lights off earlier at night and not leaving it on. It's little things. Maybe I don't gun the motor on the highway, which I'd like to do, but I need to actually say, do you really need to do that?

VH: I don't know if this is intentional, but I love how you started Beginner's Mind. Because in my mind, and my experience with you, you are larger than life, but you situate us with that stack of papers, feet up on the ottoman and big ideas about what you're going to get done for the weekend. You sort of situate us in a very specific place with you. And when I started listening, I thought, "All right, this is great. I'm about to go on a journey with Yo-Yo Ma." Thank you so much for that incredible conversation and treating us to what feels, to me anyway, like a perfect encapsulation of a life lived in search of deeper meaning that we can share with each other. Thank you so much, Yo-Yo. I really, really appreciate it.

YYM: Vanessa, thank you so much.