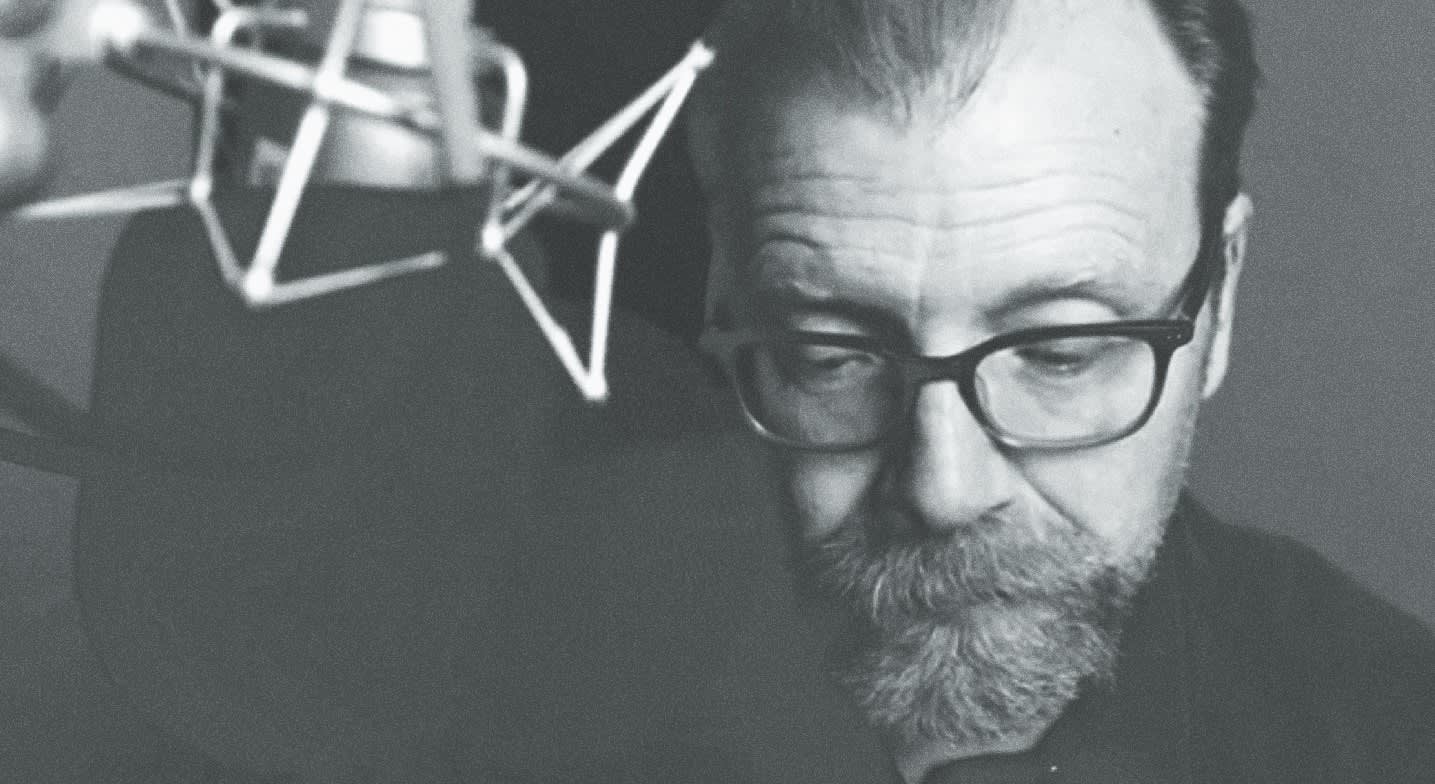

A long-awaited debut novel by an award-winning author. That sentence is packed with curiosities. Yet George Saunders (Tenth of December, Civilwarland in Bad Decline) has indeed released his first full-length novel, Lincoln in the Bardo, and it is everything you would expect from the boundary-pushing writer … and more. “More” because the audiobook features an unheard-of cast of 166, including Nick Offerman, David Sedaris, Lena Dunham, Carrie Brownstein, and even Saunders himself.

We talked recently via phone about this incredible feat, as well as the origins of the highly inventive book, and “finding the fun” as a guiding star in his writing.

Note: Text will not match audio exactly.

Doug Polisin: Hi, I’m Doug Polisin for Audible Range, and today I have the distinct pleasure of speaking with the writer George Saunders, whose book Lincoln in the Bardocame out in February. George, before we get started, I just wanted to say congratulations on the book. It’s wildly inventive and really just a beautiful piece of writing.

George Saunders: Thank you, Doug. I appreciate it.

DP: In Lincoln in the Bardo, you reimagine the night Abraham Lincoln’s visiting his son’s tomb. This is based in fact — as I understand, Lincoln purportedly returned to his son’s crypt several times. I’m wondering, where and when did you first come across this account and what about it struck you enough to turn it into a novel?

GS: I think it was summer in the ’90s, because I know Bill Clinton was president, our kids were small and we were visiting my wife’s cousin in D.C. We were just driving by that Oak Hill Cemetery and she just off-handedly said, “Oh, you see that crypt up there? That’s where Lincoln’s son was kept for a few years.” I didn’t even know that Lincoln had a son, at that point.

Then she said that she’d been reading a book by Kunhardt and Kunhardt, and in there they mentioned a newspaper account that said that Lincoln had crossed D.C. at night and gone into the crypt. Different accounts say he held the body, or he spent time with it, or stroked the hair. It’s kind of mysterious, because we don’t really know how anybody would know that. We don’t really know much about the conditions, but the fact that it was in several newspapers was interesting.

At that point, it was just hearing that weird story, kind of thinking — this is in the middle of the Monica Lewinsky thing — and so the idea that a president could leave the White House alone was odd. And then, of course, what would motivate him to do that, the powerful grief that would cause him to go there, and to think that he would get some relief from that was really fascinating.

But at the time I thought, well, that’s a good story for somebody, but I don’t have the chops to write that one, so I just kind of set it aside. Over the next 20 years I would just, every now and then, come back to it and consider maybe writing it.

DP: This concept of the Bardo. Can you talk about what that is exactly and how it factors into the story?

GS: It’s from Tibet and, strictly speaking, it means “transitional period.” In Tibetan epistemology, we’re always in some Bardo or another. Right now, we’re in the Bardo of life, which starts when you’re born and ends when you die. The Bardo that the title’s referring to is the one that goes from the moment of your death to the moment of your rebirth.

For me, it was partly because I don’t really understand the Bardo — I’m kind of a beginning student of Tibetan Buddhism — I like the idea of saying “Lincoln in the Bardo” as opposed to “Lincoln in Purgatory.” Because I didn’t really know what it was, it gave me a little bit of freedom to imagine it.

“The one thing I’ve learned is that you have to steer a project in the direction of the maximum fun for you.”

Basically it’s a realm where you die, you’re released from your body, and your mind suddenly has total sway. In some texts it’s compared to a wild horse that’s just let off its tether. That can be really cool or really terrifying, depending on the habits of mind that you’ve cultivated in life. That was a really intriguing idea to me, that our karma or our destiny or our fate in the afterlife would be intimately tied into how we lived in this one.

It’s exciting, but also maybe a little scary if you’re like me and you’re really aware of your own bad habits. It’s kind of terrifying to think of those going along with you and kind of getting supersized.

DP: Right, it’s just such an original idea. Where another writer might have opted for a more linear, first-hand account from Lincoln himself, you chose to tell this story via a chorus of voices, both spectral and historical. I wanted to ask, what did this approach enable you to do that a more traditional narrative wouldn’t have accomplished?

GS: That’s a great question. I came to writing kind of late. I was an engineer, and the one thing I’ve learned is that you have to steer a project in the direction of the maximum fun for you. You could say lively energy, or you have to try to be intrigued. Basically, if you were a musician and you were playing joylessly, nobody would want to hear you.

One lesson I learned the hard way, early in my career, was that if I tried to write to be smart or to convey a theme or from some existing plan, the result was usually pretty boring. My intuitive move, whenever I’m considering writing something, is to steer towards what feels enjoyable. Another way of saying it is, you just try to avoid the “sucky.” If you start to think of a story and a way to tell it, and your reaction is kind of like, Ugh, that’s going to be hard, then you don’t want to do that.

So in this one, I had that seed of the idea, of Lincoln. Whenever I’d think about writing I’d go, oh wait, Lincoln’s alone in a graveyard, so is that a 300-page internal monologue by Lincoln? That’s hard, a lot of pressure. Really, all of the technical weirdness of the book was just me trying to find a fun way of telling the story that I felt also had a deep reserve. When I think about writing ghosts, for example, I get really happy. I feel like I can do that all day and all night.

One of the principals of composition, I would say, in fiction, is you want to do what you can do a lot of. You want to do what you’re enthusiastic about and what rings your bell. In this case, almost every decision I made was on that basis. I didn’t want to do Lincoln walking along, thinking like, “Four score and seven minutes ago, I did enter this graveyard.” That felt like a buzzkill.

We talk about technical innovation as if it’s something you design in advance to allow your lofty ideas to come forward, but for me it’s more like suckage-avoidal, suckage-avoidance. You come up with something because you can bear to do it, as opposed to the more conventional route with a historical novel, which, to me, seemed in advance kind of ponderous.

DP: To go down that path of the suckage-avoidal, I noticed that in the scenes that take place within the cemetery, there’s a kind of deliberate and playful disorientation in the way it’s structured. Characters speak and then they’re given attribution. So at times you’re unsure of who’s speaking until they’re finished and they’re named. I couldn’t help but think this effect really mirrors the kind of distorted perception that the spectral characters possess. Was this your intention? Was this an example of you finding the fun?

GS: Yeah, that was a side benefit of that. There’s a Russian writer I really love named Isaac Babel, and he’s famous for a book called Red Cavalry — they’re war stories. One of the main things those stories do is mess with your head. They’re not told in a linear way, you’ll find that you suddenly … the point of view jumps an hour ahead and a mile away without any kind of smoothing. In reading him, you see that one of the reasons he’s doing that is he’s trying to mimic the confusion that a person would feel in battle for the first time.

Here, I felt the same thing, that if you … whatever happens when we die, it would be pretty surprising if it was what we expected. If you died and went, “Yeah, this is pretty much what I planned on.” We don’t know what it is, but I’m sure it’s not going to be neatly within the realm of our pre-imagination.

“The ‘Truth’ with a capital ‘T’ is kind of the juxtaposition of all the many, many, many truths that seem true to people at the time.”

Part of the challenge of the book was to try to just lightly mimic that effect, that whatever’s going on here is odd and it’s not scaled to human expectation. All the things you’re mentioning, like the format and all that, that had the side benefit of making the reader work a little bit. Hopefully not too hard.

The other part of it, for me, is that a writer does a lot of thinking about consciousness. What is a human being? How does a human being think? What is the meaning of all this human activity? For me, it seems like the simplest model is, we’re basically a bunch of thinking or consciousness-making machines that are roaming around the face of the Earth. While we’re making that consciousness, we’re very firmly ensconced inside of it and we believe that it’s the only consciousness, really. The world is putting on this big show for us.

It seemed to me that that would be the most truthful way to look at the afterlife, too; it’s really just a series of disembodied minds, thinking their thoughts, convinced that they’re eternal and they’re central. I guess what I’m trying to say is, I had no interest in doing a traditional narrator, because again, that’s not suckage-avoidance. If you say, “It was a dark night in the cemetery as Abraham Lincoln paced in.” To me, that feels false; I don’t know who that speaker is. But I felt like if I’d said, okay, you guys all just … all you ghosts talk among yourselves, or think among yourselves, that seemed to me, first exciting and fun, but also somehow truer to what the world actually is, at its essence. If that makes sense.

DP: I noticed that you began to play around with these shifting perspectives in a way that I can only describe — and maybe as a fellow guitar player, this will make sense to you — as a sort of delay or feedback loop. Can you talk about that effect? When did you first realize you could utilize it and what are you trying to convey by using this echo of characters?

GS: Part of the quality of life, I would say, is that all these different perspectives are running around observing the world and constructing a worldview. They’re often — as we’re reminded in these political times — they’re often drawing from different data sets; that data is falling on a mind that’s differently disposed. It seemed to me, in some way, especially when you’re looking back at these distant historical events, the “Truth” with a capital “T” is kind of the juxtaposition of all the many, many, many truths that seem true to people at the time.

Of course there’s objective truth, but when we’re looking at people’s accounts of it, it seems the real truth lies in the accretion of all these different versions. Even if they don’t reconcile, we have to take into account, for example, that a slave owner in the deep South had a certain point of view that he could articulate very well and very passionately, and the abolitionists in Boston had that. Those two things were not really in argument. They were both existing separately and refusing to engage.

To me, the best artistic effects happen when you do something almost inadvertently.

Anyway, one of the things I stumbled on in the book, as you’re suggesting, is the idea that you could just start these voices up and let them openly contradict each other, let them talk past each other, let them tell the same story in different ways. Somehow that actually mimics what I found in all the research. In retrospect, we make a nice neat story of it, but in real time, if you look at the literature of the 19th century — for example, there’s an incredible book called Patriotic Goreby Edmund Wilson, a series of essays about literature in the 19th century — it’s amazing how little agreement there was on the basic facts or values or goals.

To me, the best artistic effects happen when you do something almost inadvertently. The next day you’re reading it and you go, “Oh, wow, that’s weird. Okay, I approve that message,” and you let it stand because those effects are much more complex and ambiguous than anything you could think of in advance. In that model, the artist’s part of the job is to just see what you actually did, even if you didn’t mean to, and say, “Okay. Yeah, I’ll take that.” This thing you’re talking about is in that category, for sure.

DP: You mentioned your research. What was the research like for this book? Was there ever a moment where you thought, I’ll just turn it into a work of pure fiction, or did you always know that you wanted to inject some sort of historical element?

GS: It was maybe the other way. I started out thinking it’s just a novel, I’ll just make everything up and then, somehow … I had a lot of existing knowledge of the events around Willie’s death that were informing my emotional reaction to the material. At some point, it became clear that the reader also had to be given access to those details that were so heart-rending and moving.

Then it was a matter of how: How do you get history in something like this? Again, in this suckage-avoidance, I didn’t want to do — as much as I like these books — I didn’t want to do a Gore Vidal or a traditional historical novel. I just don’t have the chops for that, I can’t work up any enthusiasm. So then it became, how do I get this historical stuff in there without making it become a goiter on the book?

At one point, I remember having this very frank little artistic conversation with myself and I was frustrated. I thought, well, how do I know it? How do I know all this stuff? Then it was just like, boom, I know it from maybe seven or eight history books that I’d read over the years. I just flashed onto this idea of typing all that stuff up and then taking some scissors to it and arranging those into separate chapters and trying to tell the story that way.

One of the cool things about that moment that kind of confirmed it for me as a decent idea, was that then there would be matching between the format that the ghosts are presented in, with the texts and then the attribution, those exactly match the standard way we present historical text. That was one of those bonuses, where like, oh yeah, that’s cool!

So now a ghost and Doris Kearns Goodwin are going to be presented in exactly the same frame. That was one of those little confirmatory things that make you think you might be on the right track. For me, this book was always about the heartfulness of that action of Lincoln, the emotional … the sadness of that and the deep quality of his grief.

All along, my mantra was: Don’t do it unless it contributes to the emotion, and do anything you do in service of the emotion only. The historical stuff wasn’t really … I didn’t particularly want it in there, but it seems to me that the stuff with Lincoln and Willie wouldn’t be nearly as moving if the reader didn’t know the history that I knew about.

DP: I was wondering, what do you find compelling about Lincoln, both as a figure and a man? Has your perception of him changed over the course of writing this book?

GS: Yeah. At first, I was just trying to avoid him. I thought, maybe I can do this without even … I mean, he had to be in the book, but I didn’t want to take him on because so many people have in the past, and it’s sort of like writing a book about Jesus, or something like that. The book will tell you what you need to do and at some point you’re like, I can’t really avoid this, I have to take it on.

I did a lot of reading, almost casual historical reading. Whenever I’d find something about him, I’d read it. I tended to focus on the time right around Willie’s death.

With Lincoln, you see him going from a smart, ambitious, self-educated, local Illinois politician who lucks into the presidency. Then, a little bit like President Obama, he gets in there and sees that he’s in the middle of a disaster — financial, in Obama’s case, and the Civil War, in Lincoln’s case. You track him and it’s unbelievable that it’s only five years that he’s president, because he goes from being pretty pragmatic about slavery and willing to continue it if it’ll keep the country together, and so on.

Then by the end, the days before his death, I think, he was certainly way ahead of his time, maybe even ahead of ourtime in his understanding of the spiritual dimension of our democracy. In other words, as somebody who was enculturated in a kind of casual racism — I mean not socasual racism — by the end, he had gone through to see that it was absolutely logically and morally required that we make everybody equal.

You could see that he was already looking ahead. He had a way of planting an idea in the public’s head, by saying that he wasn’t thinking of it. He says earlier, in some of his debates with Douglas, “Of course, I’m not ever claiming that there should be intermarriage.” Then sometime down the line, you see him start to move these things forward.

I just see him now as a spiritual, very advanced spiritual being. In Buddhism, I think there’s a term, bodhisattva, which means someone who’s so spiritually advanced, that his own interests recede and his concern for others gets huge. We see this with Lincoln, he’d be in a meeting or something, and even when he’s being insulted you could see him managing the situation to produce the effect that he needed, to produce benefit for the people around him.

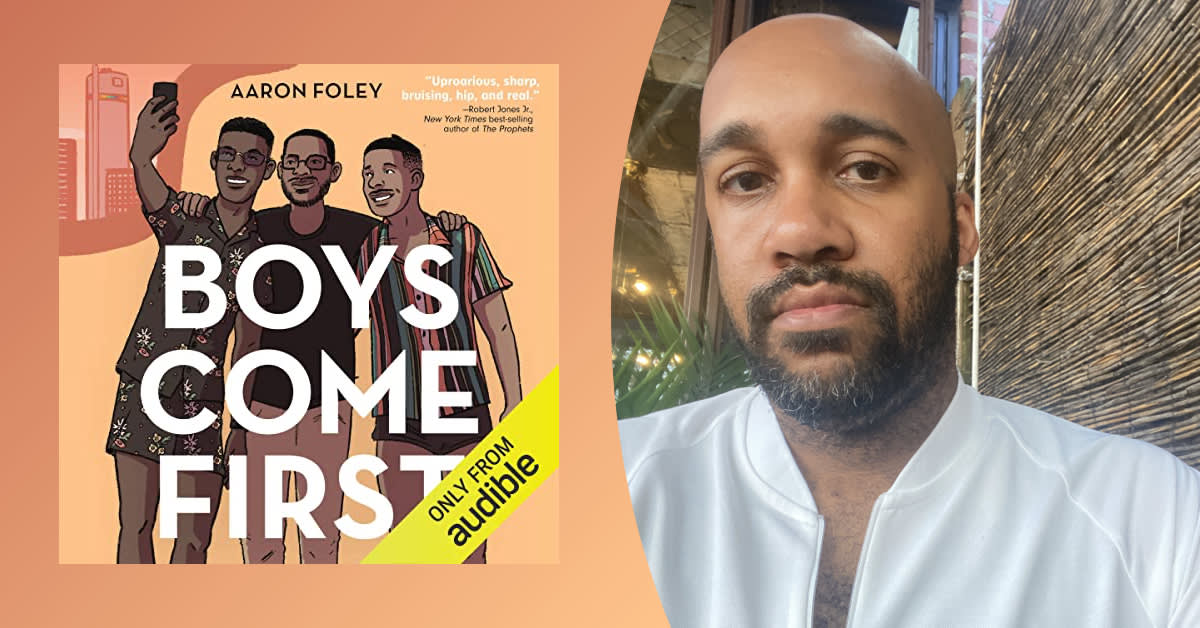

DP: Let’s talk a little about the audiobook, since it’s truly an accomplishment. One hundred and sixty-six voices, one for every character in the book, with no doubling. I read that the producer, Kelly Gildea, she mentioned that 17 different studios across the US were used to record and Penguin Random House Audio is applying for a Guinness World Record, for most individuals’ voices on a single audiobook. Was there ever a point where you thought: This is a crazy idea?

GS: Oh yeah. At one point while I was writing it, I thought, obviously when it comes time to do an audiobook, I’m just going to decline, because it’s too … it would be not only difficult, but I think it would be dull for one voice to read it with all the attributions; it just looked impossible.

Kelly and I had worked together on my last book and we had so much fun with it. When she called, I said, “Would it be possible for us to do this with a bunch of actors and a bunch of voices?” I expected an explanation of why that wasn’t possible and she was just like, “Yeah. That’s a great idea. Let’s do it.” Then, she, I mean, really all the …

It is an amazing accomplishment, it’s all her. She went off and she … I don’t really know how she did it! She got an incredible cast and then the coordination for it was just, like … She’d call and say, “I’m recording your mom, remote from New Orleans, and I’m recording your friend from this place.” It was an amazing thing. I give all the credit to her. It was mostly, again, out of that spirit of “I don’t want to read this whole thing, I can’t do it.”

I do something when I’m [narrating] that’s similar to when I’m writing, which is to … imagine you as an intelligent, sympathetic presence who’s rooting for me to tell you a good story.

When you’re researching and you’re reading in that time, you’re struck by the variety of voices, of American voices that were weighing in on the Civil War. From the super-super-educated great writers, James Fenimore Cooper, and then all the way down to people who can barely write, are firing off these letters to Lincoln, in every region and every dialect.

I really get excited about the possibility of mimicking that in the audiobook. Could we have, just by casting our net really wide, which we had to do to get that many people, if we could get some mimicry of that American chorus. I’ve been listening to it and it’s exactly what I hoped for … you hear a Minnesota accent, you hear a Southern accent. You hear every different voice and I really love the effect.

DP: Nick Offerman and David Sedaris, they’re no strangers to narrating their own work. I think they really give two incredible performances. I was really moved by how well the two of them embodied the characters of Vollman and Bevins. Did you give them any guidance in their performance?

GS: No, no. (Laughs) I just was so happy, they were all so generous to do it. I mean, the only guidance I ever gave anybody was just, “you tell me.” These guys are so talented. When you hear actors reading, acting, you realize what the skill set is. I would say, from what I saw on this project, it’s kind of like being intensely open to what’s on the page and, I think, a lot of intuition. There were a lot of things that people, Kelly told me later, people just kind of did. They just had an idea and they went with it and it works. I think Kelly did a lot of directing and coaching, but for me, honestly I just sat back and wondered at it.

I would get emails from Kelly saying, “So and so came in and I’m crying right now.” Or “you can’t believe where so and so took this.” For me, it was just kind of, like an audience … I was just with the audience, for this.

DP: Your performance as Reverend Everly Thomas was also one of my favorites. I thought that it was spot-on casting, since it seems to me that the Reverend is privy to information that the other inhabitants of the cemetery are not. That’s knowledge that you, as the writer of the book, also possess. I’m wondering, maybe I’m just reading too much into this, but was it your idea to read this part?

GS: No, it was Kelly. My idea was to not read a part, because my voice … I remember Leo Kottke, the great guitarist, he once said his voice sounds like geese farts on a muggy day. That’s how I feel about my voice. I was really advocating for me not to be in it, but Kelly was insistent. Yeah, you’re exactly right. That Reverend guy was interesting, because he was kind of a side player in early drafts, and then, without giving too much away, there’s a …

The longest chapter in the book is him giving us an idea of what happens when somebody leaves this Bardo space and goes on to the next realm. That just came out of nowhere, it kind of wrote itself. I’m like, oh god, now I have to deal with this. In revision he became, exactly as you put it, he’s the one who really knows 30% more than anybody else in the graveyard and he’s kind of withholding it. He’s probably the closest we come to a narrative presence. The closest to somebody who really understands the whole game.

He’s kind of my surrogate in the book. He’s the one who was, at certain points, leading me down the path, like, “Well, George, if you said this on page 20, then this has to be true on page 90, right?” I’d go, “Yeah.”

DP: How was the experience of recording for you, compared to say when you were reading Tenth of December, or when you read for a live audience at a public event? How was this experience different for you?

GS: It was different, because he’s supposed to be about 20 years older than I am. I said to Kelly, “Should I try to do a voice?” We both looked at each other like, nah, that’s probably not good. She said, “Just read really slowly.” Because I talk naturally very quickly, I’m from Chicago. For me, it was just a struggle to read very slowly, like an old guy.

In Tenth of December … usually, one, it’s contemporary voices that are very pronounced in my head, anyway. I can suddenly just find myself talking like this for no reason. That comes pretty naturally. In the stories, in a contemporary voice, I kind of know those voices; I know which ones I was drawing on to write.

In this book it was a little different, because there’s so many people. One of the challenges was to try to make an illusion of a lot of different voices. What I found was that meant you had to subdue all of them a little bit. Sometimes I have stories that have two or three voices, and you can go really over the top with them. One way to distinguish voice one from voice two is to make them so radically different in the way that they sound.

In this book I knew I couldn’t do that 160-something times. I took a little cue from Tolstoy, and what he’ll do, in like War and Peace is, he’s not really too worried about voice, as such. He’s not really doing a lot of straight internal monologue, he’s just tagging each person with a slight variation. Say this guy is really a fan of gambling, or this woman is constantly preferring one child over the other, something like that. That was part of the thing, was to subdue all the voices and try to keep them basically on the same plain, so that the illusion of many voices could be evoked.

DP: Have you picked up any tricks, or vocal warm-ups that you do, before you start reading?

GS: No. The only thing I have ever been told — and this goes back to when I was in fourth grade and I was a reader at Catholic church — was, “slow down.” My mind goes really quickly and I tend to talk really fast, as you’ve probably heard, I sometimes lose track of my syntax, as I’m talking that fast. The only thing I try to do, well, it’s slow down, but also I do something when I’m reading that’s similar to when I’m writing a section, which is to really try to imagine you on the other side, in a certain way, as an intelligent, sympathetic presence who’s rooting for me to tell you a good story.

The goal would be for us to get into a bit of a mind-meld of intimate, one-on-one communication. When I’m writing, that’s definitely my whole mantra, is just to try to bear the reader in mind as a wonderful, considerable person, every bit as smart as I am, every bit as experienced, and just try to gently persuade her. There’s some version of that when I read. I’m not that talented of a reader, so I can’t do it as acutely, but … imagine there’s a person on the other end who’s very attentive and you’re talking to her. That’s really the only trick I know.

After hearing these actors, I’m like, yeah that’s not enough of a trick, because there’s an incredible level of presence in the performances in this book, that I really was in awe of and I’m trying to learn from.

DP: Was there a performance that ended up moving you more then you thought it would?

GS: Man, there were so many. I don’t like to call anybody out and disrespect anybody else, it was just … I’ve been listening to it and it’s kind of, what’s amazing to me is when you see so many people inhabiting your words, it sounds a little corny, but I had this idea — that I just talked about — that writing and reading is a form of high level communion, between two people who don’t know each other, maybe they’re not even alive on Earth at the same time, almost like two fish rising to the surface at once, the same surface.

I got a real sense of that in so many of the performances, when you would hear somebody do an inflection that was exactly the one that was inside my head, or even better, they’d find something that I didn’t.

That underscored this idea that when we’re reading a book or writing a book, you’re in an act of co-creation. The reader and the writer are both trying to dress up and present their best selves and then there’s that moment, when suddenly, as a reader, you’re not exactly you anymore, and likewise, as a writer, you’re not really you. I’m not …

When I’m writing something that I think is good, I’m not really this guy, so limited and so kind of, selfish and defensive and all these things that I am. I temporarily get to lift out of that costume and be a better version of myself. I had that experience many times listening to the audiobook, just like, yeah, that person knows that section better than I do, or they know it in the same way that I do. That was a really a deep experience.

DP: Throughout the book, and honestly, this happens whenever I read or listen to any of your work, I found myself thinking about something I read by the late David Foster Wallace, who I know was one of your friends and colleagues. Just to paraphrase from his essay, “E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction,” he says, the next real literary rebels in this country will have the childish gall to treat plain old untrendy human troubles and emotions with reverence and conviction. Is this something you think about when you write and do you think modern literature is doing this enough?

GS: I think literature has always aspired to do that. I think, in any time, you could pick any time, and you’d find that there was a middle ground of literature that was trendy or was that time’s version of cynical or clever. At the top, you’d find a few people who were in communion with something bigger.

The way I would put it is, you don’t want to spend your life writing about stuff that doesn’t matter. You want to try to pull out of the temporal mediocre and write in a way that is meaningful to everybody. This goes back to this idea of being intimate with your reader. Since we’re all down here and we’re all dying and aspiring and loving and feeling inadequate, all these things that we all are doing all the time, what a relief it is, when somebody looks at you and says, “Yeah, me too.”

I think that’s probably been a battle that every generation has fought. If you go and look at that period in Russian lit, in the 19th century, there were a bunch of mediocrities doing the same old crap, but we don’t know who they are anymore. But Chekhov, Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, those guys live on because of exactly what David was describing.

DP: What do you think you’ll do next? Do you think you’ll return back to short stories, or do you think you’ll work on another novel?

GS: Honestly, I don’t know. This is the first time in a long time that I literally had, in terms of fiction, an empty desk. I always try to avoid that. I’m kind of just waiting. I’ve written a couple of introductions for other writers work and I’m working on a TV pilot, just for fun. After this tour, I think I’m just going to take a deep breath and, again, see what’s fun.

Part of my mind is saying, “Yes, another novel” or “no, not another novel.” I’m really trying to be honest and just say, I’m going to sit down and see what seems really fun and trust that that will lead me into … It’s funny, I’ve found that if I go by that idea, of trying to do what’s enjoyable and what I’m being pulled to do, then the other stuff, the thematics and all that, that all takes care of itself.

Looking at it after the fact you can see maybe a continuum of interest, but in the short term it’s just trying to … Honestly, it’s about trying to come to the writer’s desk every day with a certain sense of “this will be good, this will be fun.” Apart from that, I’m not planning much. (Laughs.)

DP: George, I just want to say thank you so much, for taking the time to speak with us today. It was truly an honor.

GS: Thank you, Doug, for those great questions. They were really a pleasure to engage with.

Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders is now available on Audible.