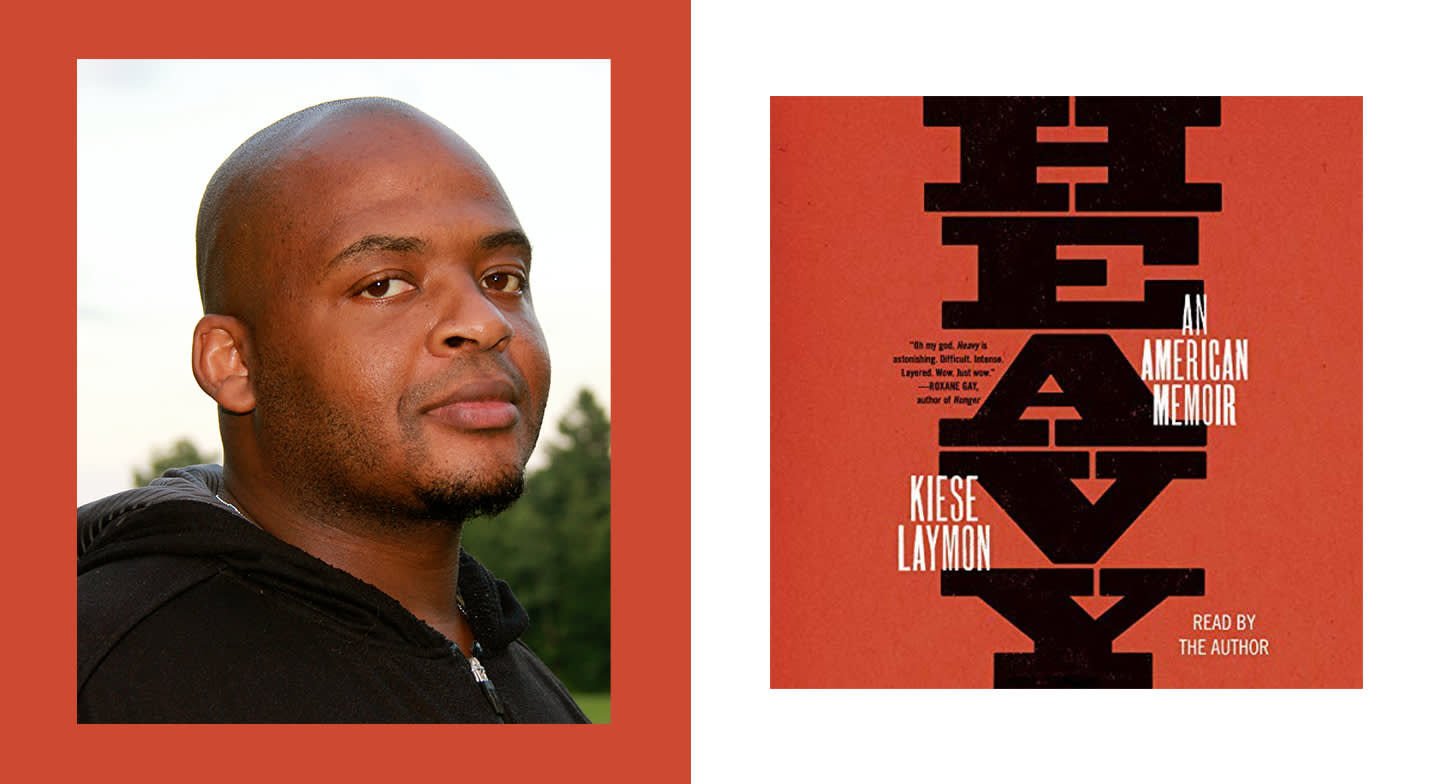

It was clear from the start that the audio for Heavy was something special. Writing in the form of a letter to his mother, Kiese Laymon left everything on the table to tell us about his childhood as a black boy growing up in Mississippi. In poetic delivery, he details the eating disorders, addictions, and bittersweet family love that have followed him throughout his life.

As the Audible editors’ memoir specialist, Rachel Smalter Hall made sure everyone caught on to the talent that Kiese brought to the table, as well as the unprecedented intimacy of what he chose to share. Listen in as Rachel and Kiese talk about what it meant to literally find his voice with his incredibly vulnerable and frank work.

Note: Text has been edited and may not match audio exactly.

Rachel Smalter Hall: Hi, this is Audible editor Rachel. I am our memoir editor here at Audible, and I’m so excited to introduce our guest today. Kiese Laymon first won my heart with his debut novel, Long Division, about an aspiring quiz contest champion who time travels to 1964 to confront the Klan. His next book, a collection of essays called How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America, touches on subjects ranging from his college suspension for publishing a racially charged essay, to Beyoncé’s significance as a southern black musician. His most recent book, Heavy, is a memoir about his relationship to his family and his body, and moved our entire office so much that we named it our 2018 Audiobook of the Year, the first memoir to ever claim that honor.

Kiese, thank you so much for being on the line with me today. I’m so excited just to be able to talk to you and talk about Heavy.

Keise Laymon: I’m so happy that you want to talk to me, so thank you for having me.

RSH: I have to ask you right off the top. You have this tweet on your timeline that says, “My momma said she was proud of me. Goodnight y’all.” Was that in response to winning Audiobook of the Year?

KL: Yeah, it was. My mother, she’s a teacher, and she was really upset that I couldn’t read my first two books. So she was the one who really pushed me to read Heavy. I wanted to do it but I wasn’t pressed to do it. But she was like, “Kiese, that’s too personal. You really need to read that yourself. Only you can read it right.” So she was really proud of me, and, you know, this book is a really hard book because it’s written to my mom. It directly addresses my mother, talks about a lot of things like addiction and weight gain, weight loss. So I’d gotten some good reviews on the book, but when I won that Audible Audiobook of the Year thing she was just like — she cried, she just laughed. I don’t know. She got super, super excited.

RSH: Oh my goodness. Does she tell you she’s proud of you often or was that a special little moment?

KL: No. No, no, no. [Laughter] I mean I think she’s proud of me often, maybe. People tell me that, but she does not. I don’t remember the last time my mom told me she was proud of me. I’m not trying to make this into a “woe is me” thing, but yeah, she didn’t tell me she was proud of anything that had to do with that book until I won that. You know, I think the interesting thing about winning that award was that she actually heard it from her friend. Her friend was like, “Did you hear what Kiese won?” Yeah.

That’s the feeling I wanted the listener to have, like they’re watching me talk to my mom using an art form that she actually gave me… She gave me reading and writing and revising.

RSH: Wow. I’m kind of speechless. I need to gather myself because that’s amazing. I’m so happy that she was proud of you and that, yeah, that’s really special. Collecting myself, you said that your mom is the one who pushed you to read this because it’s so personal. Is she the first one who had that idea? Did that come up with your first two books? I just have noticed that your work has become progressively more personal and this is the first one that you have narrated yourself. Walk me through the progression of that.

KL: Yeah, I wanted to read those first two books, but my first book deal was with this independent press out of Chicago, and I think they just didn’t trust that I could read Long Division, which would’ve been a hard book to read, but I wanted to do it. I didn’t think that they trust I could read how to sell it because the editor at that place and publisher, they hadn’t actually heard me read. I think the assumption is often actors will do a better job than writers. But, after those first two books came out, those two books were read all right, but I just knew I could do them, not better, but just more of what I intended. When I heard about this thing, I think initially PJ, my agent, was thinking that some actor was going to read this one too. Then I just was like, “Let me. Can I do it? Can I try? Let me see.” It was tough though. It was a tough experience. I read it in an attic. I don’t know if we want to talk about that.

RSH: Oh yeah!

KL: An attic in Oxford, Mississippi. I’m looking across from this really kind white guy, but he’s definitely the kind of white guy that I would never ever be looking directly across unless I was at Sears trying to buy a dryer or something like that. You know what I mean? It was just very weird. It was a weird experience. But, I fell into it, and it was hard, bodily it was hard too. It was really hot up there. It’s Mississippi. You gonna record audiobook, it needs to be hot.

RSH: Yeah, did you have air conditioning in the studio?

KL: I don’t know if that brother had air conditioning up there or not, or maybe he turned it off. I don’t know, but it was good. You know what I mean? I wish we would’ve recorded the making of the audiobook because I think people would be sort of astounded. Again, it was a home studio, so every time a big truck, and there are lots of big trucks in Mississippi, rolled by the house, we had to stop because apparently you could hear the truck on the recording. Or next door when the neighbor had to raise the garage or the kids came out. You could hear it. I couldn’t really hear it, but he could hear it, so he was like, “Okay, we gotta record that over.” After a while I got used to it, but initially I was like, “Oh lord, this is gonna take forever if we’re stopping after every few words because cars are passing the house.”

RSH: How long did it take you to record the whole thing?

KL: Well I recorded the first half maybe in a week or so, and then I had to go to do some book stuff out on the west coast. So then I went to the west coast for like three weeks and I came back and I finished it in another week. So all together I think it took about a little bit over two weeks to do.

RSH: Okay, wow.

KL: Yeah.

RSH: I wanted to ask you a little bit more about that process of recording. It’s hard enough I imagine to write your story and put it out there as you’ve done with Heavy. I imagine it’s a whole other to speak it out loud. What was that like for you?

KL: Yeah, that’s a great question. Yeah, that question makes me go back. One of the reasons I wanted to read the first two books, because I’m a very oral writer. I’m steeped in literary tradition and all that, and I want to do literary tricks and blah, blah, blah that only a few writers in the country even care about, but I’m also very oral. I like to read my stuff back to back to back to back when I’m trying to find the rhythm of it. This book especially, you know, I’m trying to play with shorter sentences and longer sentences, but I’m also an older writer. I’m 44. When I wrote both those other books, I started them when I was much younger, so back then, when I was writing and reading, when I would read from Long Divisionfor example, all of the voices had to be distinct from one another. There are lots of voices and lots of characters in that book.

For this I was also thinking, okay, there are a lot of characters in this memoir. Do you want to go back to that thing where you try to read them all in different voices? I don’t know if it’s because I’m older and/or because of the subject matter of Heavy, but I was just like, “You know, maybe you can notreally make your voice sound different for every character and the reader/listener can just hear the distinction between people without that. Just let people get lost in the trance of the voice, and really just remind people with your voice as much as you can that this is actually written and spoken to my mother.” So in my mind, I kept imagining myself sitting in front of my mom when I was a kid with a notebook and having to read to her something that she’d made me write.

That’s the feeling I wanted the listener to have, like that they’re watching me talk to my mom using an art form that she actually gave me, which is what she did. She gave me reading and writing and revising. That’s what I wanted the feel to be. But for me, that was a big decision. So to do that, I couldn’t do all the voices the way I wanted to. I needed to be a little bit more somber. Do you know? And so-

RSH: I do.

KL: I think it was a good decision, but yeah.

RSH: Oh, I’m so glad you made that decision. You know, I’m really picky about memoirs, especially audio memoirs. I say that’s my jam, and I feel like it makes it come across as so much more personal and warm, and that just is so necessary for this story, which is you telling us your truth in your own voice. I think, so applause. One listener here thinks it was perfect.

KL: Thank you. It’s hard too. You know, I just have so much more respect for what the [narrators] of audiobooks do, because I think anytime we read in front of people, most of us there’s this urge to, again, seem super literary or to change our voices, so the voice that we read in sometimes is not the voice that we talk in. So I guess I wanted a little bit of that in the book, but I wanted the voice to really be a voice that I talk to my momma in. The voice is that y’all hear in the audiobook are the voices that I use when I’m telling my momma stories or lying to my momma or trying to tell her the truth or asking her. There’re slight intonations in the voice that I think I use, and I think that’s one of the reasons that it made my mom so excited too, because she likes the book, but she loves the audiobook.

RSH: So she has listened to it?

KL: Well that day, yeah, I mean that’s what’s interesting. That day she found out, because I didn’t tell her. I found out before but I didn’t tell her. Her friend told her. Then she went and she started listening to the audiobook. Then she called me and the audiobook was playing in the background. I don’t know if it was on her computer or on her phone, and then she was just like, “Ke, I’m so proud of you. So and so just told me you won Audiobook of the Year. I’m listening to it right now.” That book had been out in the world for a while, you know? She saw early drafts of the book, so somehow just hearing it in my voice in some way made that book different for her. She appreciated the book before, but honestly, I think that because of the personal nature of it, I think she was able to hide from some of the emotive impacts of that book, but I think just hearing my voice read it to her, made her so she couldn’t hide.

I wanted to see if the audience was willing to give me their heart, but also trust that it was okay to laugh in situations where you might not feel okay laughing.

I think it made her realize she didn’t need to hide because we were in this together, and really the rest of the world is in this together. That’s what I’m trying to say with this book. I teach, and I know if my students told the world the truth about their relationships with their parents, I think most people would go, “Oh my God.” But if everybody’s going, “Oh my God,” then I think there’s something normal about the absurdity and the bizarreness and the suffering that a lot of us go through with relationships with our parents in this country. So the audiobook made my momma feel the book the way I wanted it to be felt, and so I’m very, I’m so thankful that I could do that.

RSH: Wow. Do you think it changed your relationship with her at all? I mean how has that evolved since the book has come into the world and since she listened to the audio?

KL: Yeah, you know, so again, my mother was involved in this process a long time ago. I started, she was going to be more central to the book, earlier I was going to be a little bit peripheral. So she’s been part of this process for the last four years, but it’s weird. The only person I read the book to before I read it to the world was my grandmother. My grandmother is older and she’s got a little bit of dementia. She’s just been through a lot. She appreciated it. I talk about this in the book, but she’d go to sleep while I was reading it to her and then she’d wake up and she’d be like, “Oh that sounds so good. I like that.” Blah, blah, blah, blah. But, my mom hearing the audiobook absolutely I think enabled us to have the beginnings of some harder conversations that the regular book just didn’t, particularly not just, because we were able to talk about gambling. We were able to talk about weight, but I think the audiobook enabled us to have conversations about intimacy and sex, and sexual violence that the book alludes to, but my mom and I just hadn’t … We hadn’t had the courage to step into. I think my mom hearing me read this book to her enabled her to ask some questions, and then it really gave me the confidence to ask her some questions that I’ve been afraid to ask her. Do you know what I mean? So again, I’m not trying to make it seem like doing audiobook is the magic pill and can heal everything and maybe if Trump does an audiobook the world would be safer. I’m not trying to say any of that, but in my situation, it definitely made my mother and I closer. It gave us a lot more to work with, and we’re working with it, so I’m very thankful for that.

RSH: Wow. You know, you brought up something I wanted to talk to you about, which is that it’s not very common I don’t think for people to talk about men’s issues around eating disorders or body image issues. How has it been like for you to have that part of your story out in the world?

KL: Yeah, it’s scary. It’s scary because you walk around in the body that you write about. You know what I mean? So it’s one thing to write that stuff in the dark of your office or your bedroom and then to get it printed, but when you go around the country reading this book or people have this book in their hand and they’re reading literally about your body while watching your body, and they think they know one narrative of your body because you gave it to them, I mean it gets a little complicated.

But that’s the point of the book, right? It’s heavy, it’s hard work, but we have to do it. Particularly like men, and cisgender men, I think particularly we need to talk about our relationships to food and intimacy and violence and sex, and how that impacts what we put in our body. What we don’t put in our body. How we sometimes indulge in mirrors. How we sometimes run away from mirrors. You know what I mean? I just think there just hadn’t been enough cis-straight men in my life talking with any sustained care about our relationships to food and body. And I just wanted to, not be the first, because there are a lot of people who’ve definitely done it, but I just wanted to add my work to the list of people who were trying to do that work. Because it’s important work, you know, and intimate work that I think requires us to also look into family history.

When you start talking about, like my relationship with just eating way too much and my relationship with starving myself, and more importantly, how good both of them felt. H ow it felt so good to eat too much. How it felt so good to starve myself. But I will say that the eating too much is harder to write about than the starvation. The talking and writing about the starvation. And that says a lot about the country, but also says a lot about me, where I am still. It’s easy for me to talk about how I didn’t eat for however long or how my body fat was super low. It’s easier for me to have that conversation than to talk about when I’m trying to find pizza in garbages.

RSH: Right, which is one of my favorite scenes in the memoir, I have to say. It was so, so raw.

KL: Oh yeah, for real. Also, that’s so good to hear, I mean in a really f**ked up way. Oops, sorry. In a really messed up way, it’s so good to hear that, because a lot of those stories, while being tragic, are also just funny. As a writer, and as the reader of the book, I wanted to in some way see if the audience was willing to give me their heart, but also trust that it was okay to laugh in situations where you might not feel okay laughing. That to me is one of the funniest scenes in the book, even though it’s pretty sad, you know?

RSH: Yeah.

KL: There’s another scene where this student of my mom is molesting me. It’s not funny at all, but what’s funny to me in that scene is I really was worried that she wasn’t going to like me because my breath was smelling like pork chops, rice, and gravy. So it was like how do you in some way entice the reader to want to do what they don’t want to do in that situation? Because what we want to do in that situation is go, “Oh, this is so sad.” But if you try to put something in there that makes people laugh, I think readers have to make decisions. And if you make readers make decisions, they feel more implicated, you know? So that’s where I was with all of that.

RSH: Well, and that’s how we cope with our pain, right? Through humor. I mean not all the time, but it sure helps.

KL: I know I do. I know I do. You know? I know I do.

RSH: Yeah, I wanted to ask you. One of the things I really loved about How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America is this recurring theme of Black men learning how to offer love and friendship to other Black men. I found that very moving. I’m wondering if you’ve been approached by any other men who’ve related to your work in Heavy?

KL: Oh yeah. You know, you write a book and I’m sure some people expect that they’re going to win Pulitzers and New York Times Bestsellers, but I’m not that person. So I’ve been shocked by lots of responses, responses from mothers, particularly black mothers. Yeah, I’ve been really surprised by the number of black men who have talked to me about how thankful they were and are that, one, I named some of the violence that dudes do to other people.

I think people do that a lot in literature, but also that I talked about the importance of abundance in black children, and rhetorical abundance and how sometimes these things that black kids do with words are things that we do to keep ourselves alive in this nation, spiritually alive, psychologically alive, and also bodily alive. A lot of it begins with the word, and so I have to say, lots and lots and lots of black men and young black boys talk to me about how thankful they are for this section in the book called black abundance and how they also felt provoked in ways that they didn’t expect. I didn’t expect to hear that, but it makes me happy for sure.

RSH: I’m so glad you bring up black abundance, because that to me is one of the more magical parts about this book and your other work. It’s about so much more than struggle and pain, and you do talk about what you’ve called black abundance. Can you talk more about what that means to you and how you put it out in the world?

KL: Yeah. When somebody really asks me what it means, I want to just be like, that chapter is what it means. But if I had to be much more reductive, I think it just means sometimes Blackness and lack are often tied together in this country. I just think it’s important for us to remind ourselves that a lot of us come from families and cultures and places that are at once abundant. That abundance doesn’t mean that there’s no suffering. Doesn’t mean that there’s not complicity in violence, but it means that there’s complicity in violence and there’s suffering and there’s immense joy, and there’s bodily pain, but there’s also this bodily happiness.

For us in 8th grade, again, it was the words. It was using vocabulary words intentionally wrong. It was trying to use them intentionally right. It was stretching out vocabulary words in ways they weren’t made to be stretched. And it was important that we did that because it was the first time we’d ever gone to majority white schools, and we felt like the teachers and some of the parents and some of the students kind of did not necessarily accept us the way we wanted to be accepted. So in absence of that acceptance, we just wanted to make a space for ourselves in that school. That space was a language space.

For me, that space was just rooted in all of the places we ban as black kids from Mississippi, whether it was Jackson State football games or churches that we didn’t want to be in, or playing outside in pine needles and coming back in the house smelling like pine, or having your grandmomma tell you to go outside as soon as you step in the house. “Go back outside.” I’d be like, “Why grandmomma?” She’d be like, “Because you’re smelling like outside.” As a writer I’m like, “What does outside smell like?” I have no idea what she meant by that, but to me that phrase or sentence is kind of like emblematic of black abundance.

These words that on some level don’t adhere to normative structure but make all the sense in the world to the people that created the words, and then the words end up protecting those people. You know what I’m saying? So that’s what that book is also rooted in, and I’m so grateful and thankful that you see that there is, I think, a lot of irony and joy in that book, in addition to a lot of suffering and other stuff that is sort of sadder.

RSH: Yeah. I mean absolutely, I mean clearly the book has so much suffering, but I think we were all drawn to it because it has so much more dimension than just the suffering and just the pain.

KL: Absolutely.

RSH: So thank you for putting your Black abundance out into the world.

KL: I appreciate that.

RSH: Were there parts of the story that surprised you by being harder to narrate than others?

KL: Yeah, that’s a really great question. There’s a chapter in that book called “Wet”, and I just couldn’t read it initially. We were just reading the chapters sequentially, and then I just couldn’t read that chapter in that space until I … I had to go to the bathroom. I had to wash my face. I had to drink some water. I think the dude had some gummy bears or something in that room. So I just had to take a pause before I read that chapter, because that chapter’s really hard for me to read for a number of reasons.

RSH: For those listeners who haven’t heard Heavy yet, can you tell us just a little bit of what “Wet” is about?

KL: Yeah, “Wet” is about I’m trying to get away from the house where I’ve been staying while my mom is away. I’ve been staying at this house where two of my friends have been sexually abused, and I just go out in the driveway and wait for her. She finally picks me up. When she picks me up, she won’t turn towards me. She’s in the driver’s seat. I see a tear come down on the right side of her face and she turns towards me eventually and I see that she’s been punched in her face and she’s got a clot of blood in her eye. We get home, and again, I’m 11 to 12 years old. I know where my momma keeps the gun. I want to go get the gun because I figured that her boyfriend had punched her, so I want to get the gun because I want to hurt him.

She gets to the gun first. I get some ice, I try to take care of her. We go to sleep. Her boyfriend comes over to the house. I try to hurt him. I don’t talk about that part in the book. We flash to a few hours later, my mom was in the bedroom with her boyfriend who punched her in the face and I hear them having sex. I go through a lot of the emotions I felt, but I go through also a lot of what I put in my body. I put a lot of pear preserves and peanut butter in my body that night. My momma had this boxed wine. I drank mason jars of boxed wine, and then the next morning I had my first wet dream, right?

So it was a lot to write, but it was also a lot to read in that space where I was reading it. I was reading this space in a white suburb in Oxford, Mississippi, where this dude is looking directly in my mouth as I’m talking to him about my mother getting beaten, my friends being sexually abused, my response to that, and my having a wet dream. You know what I mean? So that’s just a lot to write, but it’s also a lot to convey to a sensibility that I wasn’t thinking about at all when I was writing that book. Do you know?

But I think I pulled it off, but it was definitely hard. That was really hard, and then some of the sections near the end when I was talking about gambling with my mom were really, really hard to read just because they were just hard to remember. Sitting in a hotel room hoping that this would be the last time my mother and I had these hard conversations. It’s so sad. We left that hotel feeling like we triumphed when we just hadn’t. We actually made things worse thinking that you can go into a casino hotel room and fix your relationship. It’s sort of ludicrous, but that’s what Americans do, and that’s what I did. So those two chapters were the hardest chapters to read.

RSH: It’s interesting. One is this kind of historic hurt, and then I imagine the other one’s hard because it’s so, I mean it’s almost more fresh than the hurt from your childhood.

KL: Oh yeah. It’s fresh, but it’s also I just remember that feeling. I think we, I don’t know about everybody else, but I know a lot of people I know, movies do this, books do this, television does it, we think we’re living in the moment that’s going to change our lives often, you know what I mean? So I was in that moment when I’m in that hotel room in a casino. I have $10 that I’ve taken from my partner. My mom has no money, and we’re sitting there, and we have an opportunity to do what that book does, which is talk about the hard things. We kind of start to, but when it gets too hard, we go back to what we always talk about. We both were looking at the door of that hotel room because we want to get out of there. We don’t want to be stuck having to sit our bodies that close together and talk about really where we’ve been.

It’s too close, you know what I mean? It wasn’t too close to read, but when I read it I was like, “Damn. Yeah, this is still us in a lot of ways.” Because there’s a way that I want to believe just reading that book in that room in Oxford, Mississippi is going to make everything better, and it just doesn’t. It gives us tools to make things better, but that’s not the same thing as making something better, do you know? So yeah.

RSH: Well Kiese, thank you so much for sharing your story with all of us, and thank you for sharing it in your own voice. It really has meant a lot to us here at Audible, and I’m sure it’s meant a lot to the rest of the listeners throughout the world.

KL: I’m really thankful, and again, after that book was recorded I thought y’all were gonna hear it and be like, “We can’t do anything with this shit. Why did we let this dude read his book?” So I’m really, really, really thankful that you all appreciated the book and appreciated my trying to read that book to you and to my mom. It meant so much to me, so thank you a lot.