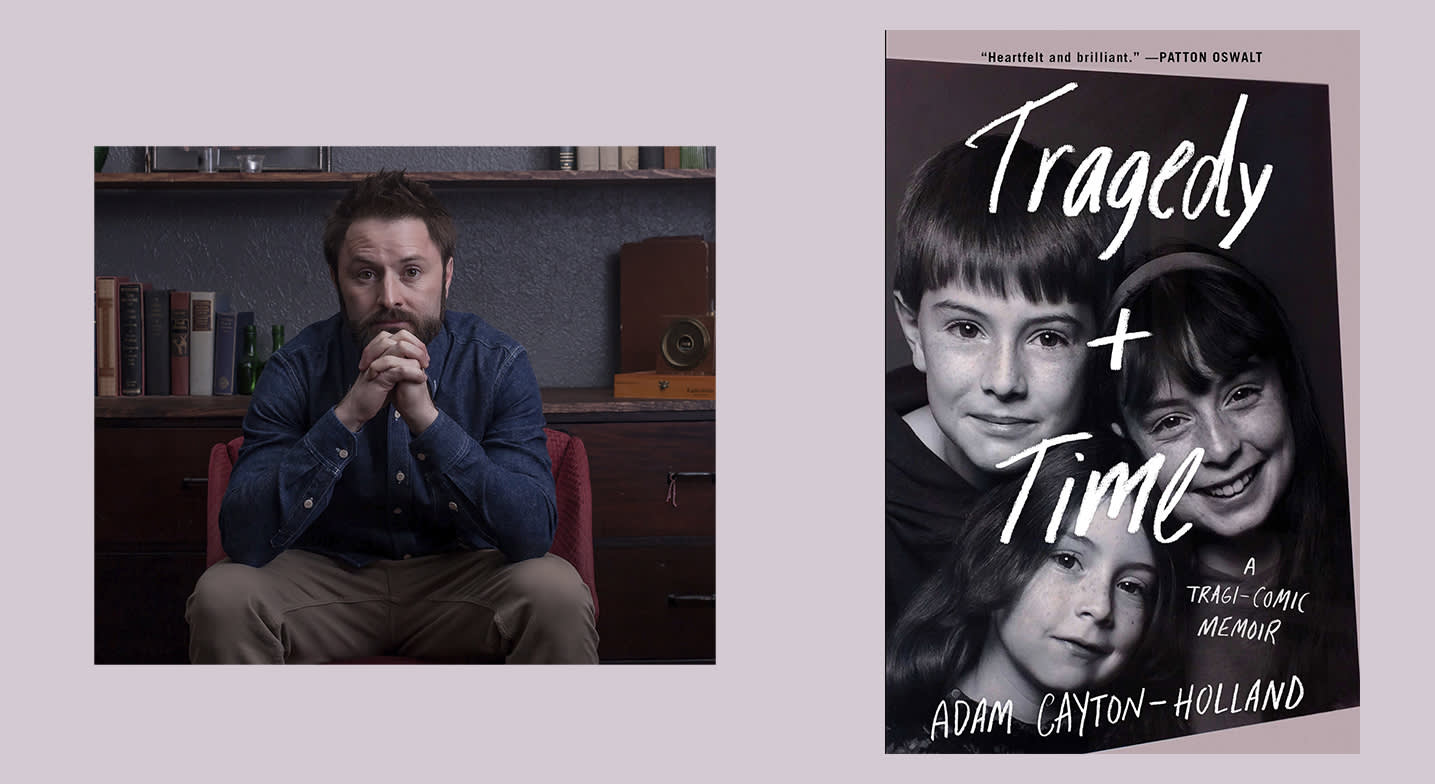

When I sat down to start Adam Cayton-Holland's tragi-comic memoir, Tragedy + Time, I'm not sure I really knew what I was getting myself into, but the second I finished the last word of the story by this comedian/actor I knew that it would be a book I would never forget.

It may be taboo to talk about how nice it was to read a book that spoke to my "struggle," since I grew up a privileged, suburban white male. But I am who I am and my family, like Adam's, has dealt with issues of mental health and the heartbreak that comes with it. I laughed and cried often during this listen, and Tragedy + Time does something I have not seen in a while: it turns the severity of discussing mental illness on its head in a beautifully comedic way (maybe unsurprisingly since Adam has been on several Comics to Watch lists), while still honoring the grief of horrible loss.

As we close out Mental Illness Awareness Week, please check out my conversation with Adam, who is also the writer, creator, and star of Those Who Can't on TruTV, about his debut work, his life and career, and what it was like to tell his late sister Lydia's story while writing a memoir about his own.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Kyle Souza: Well, thanks for taking the time out to do the interview. I read the book and really just fell in love with the story. Similar to the book, just personally I've dealt with suicide in my family and depression and mental health issues myself and with some of my loved ones as well. I think talking about depression and mental illness is not something that's necessarily ... It's kind of taboo I think.

Adam Cayton-Holland: Yeah, yeah. Well, you know and I'm sorry you can relate, but yeah, I feel like it is important to discuss.

KS: Absolutely. That's just one of the things that I loved the most about the book, was I think it flips the idea of talking about mental illness from the perspective of it doesn't matter race, religion, socioeconomic status. There's no good or bad time to talk about it. You just have to.

ACH: Yeah, well put.

KS: Thank you for writing the book. It definitely spoke to me, and I hope it speaks to a lot of people out there who can make those connections and have those conversations within their families.

ACH: Yeah, well sure. Thanks for saying that.

KS: So, you've pretty much almost always been a writer. You started out as a writer before you were in comedy, if I did my research well.

ACH: That's right.

KS: How does it feel to not only have a book published, I mean obviously I'm sure you wish it was under better circumstances, but how does it feel to have a book published and have such a positive reception? So many big names have spoken out about the book.

ACH: Yeah, I really wish I didn't have this story to tell, but I'm honored to tell it. As someone who's wanted to be a writer their whole life, this is amazing to have a book out there that's being well-received. I'm able to compartmentalize the grief and the hurt of this book. Honestly, I think I turned this book into somewhat of a tribute to Lydia, an honest look at a family, and a love letter to that family. It's great. I'm enjoying every part of it.

KS: Well you should because it's really well-done. This is a memoir, but it's a different memoir because so much of it relies on telling someone else's story as well. How did you manage the responsibility of telling Lydia's story in the right way?

ACH: That was my number one concern is to do my little sister justice because it's such a big task. She's gone, and so she can't do it for herself. So, I'd be mortified if I did even a B+ job of telling her story. I really love that girl and think she's so interesting and unique and special that I wanted to properly memorialize her, I guess, but I definitely felt that concern and burden. I'm really eager that, you know my family feels like it's a true portrayal of Lydia and that is the highest praise I can get. I wanted her to live on here in this book. I didn't want it to just be depression and grief and suicide. I wanted to also show how special she was. So, I was very keenly aware of that.

KS: I assume your family is comfortable about you publishing this. Was writing the book somewhat of a family ordeal, or did you get everything you needed to get out and then run it by them?

ACH: That's what I did. I mean, I asked a few questions here and there, but I gave it to them before I gave it to my editor. I was like, "If there's anything you want out of there, you just say it." The last thing I wanted to do was cause more hurt to my family where we'd been hurt, and I didn't want to do any more of that. But at the same time, I felt this burning urge to get this story out of me. My family's been really good about, with every member, allowing us each to mourn how we need to mourn. I don't think their first choice would be for me to go out there airing our most private pain in a public platform, but they understand on some level this is something I need to do to move past it, or even work through it as a writer and creative type. And they respect that.

ACH: So, it's hard. It's very hard. I'm sure my parents don't necessarily love seeing our photo everywhere and having this brought up when they can't control it, but they're supportive and they understand I wanted to do this, so I'm really grateful to have a strong enough family that will embrace that opportunity for me while also realizing it's a sad thing.

KS: Absolutely. I think in a pretty awesome way, you follow the family lineage there. Your dad is basically a Civil Rights' attorney and your mom was an investigative reporter, and what you do in this book--shedding a light on and making the conversation approachable about mental illness--follows in their footsteps.

ACH: Well, thanks for saying that. That's nice. That makes me feel proud.

KS: Well, you should be. You were talking at the end of the last question about how it is needed and necessary, for you at least, working through [the grief], but it's also something that's very sad. This idea of a comedically tragic memoir. Comedy and tragedy are opposing forces, which are brought into many great artistic works, but how is it to take these two opposing forces of comedy and tragedy and reconcile those while writing this?

ACH: It was never an active choice. I just needed to get this all out of me. I think I'm a funny person. So, when I write things, they come out funny. For me, they're polar opposite forces, but they're linked. I don't think life is so clean that you just experience tragedy and then move on, and now it's funny and then move on, and now it's sad again. I think it just all comes at you at once. There's gallows humor, you know. So, for me it wasn't like anything I thought about or tried to do. That's just my world view is sad and funny, so it's not a forced effort. It's just how I am. I think even before Lydia is how I was. My family, my siblings especially, we all are oozing pathos, so I think that's just where our heads are.

KS: I had read a little bit about how, and I think you said it on a podcast at some point, that your parents, even though they are these very successful people, that they came out of that '60's era and are very goofy, quirky, funny people in general. That seemed to come through in at least how the story portrays your family.

ACH: Yeah, they're some big old hippies.

KS: That's good. Well, Denver's a good place for them.

ACH: Yeah. It's a certain type that landed in Denver in the mid '70's. That might just be my mom and dad.

KS: I grew up in Phoenix, Arizona. I spent a bunch of time visiting Denver when I was down there. How do you feel about Denver now versus Denver when you were growing up? I feel like it's changed a lot.

ACH: Yeah, no. It's changed. It's exploded. My whole childhood, my friends and I were desperately being like, "Denver's cool. It's like Portland. It's like Seattle. It's like Austin." But not believing it. And now it has become that and we're all like, "Oh, goddammit. What did we ruin?"

KS: Yeah, and you made the decision to stay there, and you talk about that in the book as well. You and The Grawlix faithful and everything have kind of made Denver into a comedy destination. Do you take a great sense of pride, you know, of making Denver a hub for comedy?

ACH: Absolutely. I take a lot of pride in that. There were a lot of comics before us that were killing it in Denver for years. Comedy Works is one of the top five clubs in the country. That's all of our home club. Wende Curtis, who owns that place, is so good and supportive. There was already the infrastructure there, but I think my buddies and I represented the alt comedy boom of the 2000's. I think we were that space in Denver. It's been so great to watch that grow. I go home and there's like 20 comics that I have no idea who they are who are hilarious. It just seems like that scene just keeps churning out really funny new people, so I'm very proud and happy to have some stake in that or some responsibility for that. But again, there's so many funny comics before us that were setting it up.

KS: That's interesting.

KS: Anyway, to get back to the book. Your narration is great. I have to say, a lot of the times when you see the book is being read by the author it's somewhat of a coin flip... I mean I kind of assumed that you would be all right because you get up and talk to people in public, but your narration's good, man. I've got to say.

ACH: Thanks. That was weird, but it was a great experience. At the end of it, I was quite happy with how it all went down.

KS: Did you find some solace after writing it, getting into the booth and narrating it? Did that have a separate experience from writing something that was so deeply personal?

ACH: Yeah. The writing of it was the gut-wrenching stuff. I sobbed and sobbed and sobbed at my keyboard. That was where I did the real catharsis or purging or learning or healing, whatever you want to call it. That all happened during the writing. The reading of it was very intimate and personal, but on some level, I was really able to leave a lot of it in the page. It sounds cheesy to be like, "I needed this book to heal me," but I did. The writing of it for me was the hardest part. The recording was raw, and it's obviously intimate to go over it way more than I do it normally, but doing interviews and talking about it, for me it's the experience has already been lived. Certainly, there's new nuances to how I'm going to mourn and grieve for years to come, and those aren't written into the book, but the hard part of the book was writing the book. On some level, I'm detached from it now.

KS: I know this stems from an article you wrote for The Atlantic in 2013, which I actually did not know that that's how this came about. When you set out to write the book, did you feel at all like, "Hey I wrote this article about it. I got it out and started this process of I just needed to get this on your computer screen or paper," or whatever. However, you wrote it down. The difference between writing something in that article format and then extending it out and having it be a full book and telling that greater story. Was that difficult? What was the process in taking that and extending it?

ACH: The first thing I ever wrote was on my blog. I wrote about that in the book. I just had to get something out. I wasn't talking about it on stage. I'm this insufferable creative who has to process things through their art. So, I did that and it really felt good. It felt normalizing to me. It didn't feel like this dirty little secret I had that I was being crushed under. Just, I got it out. It's that simple. Then I had more to say, so I wrote that Atlantic article. I like to write and this is what's on my brain, so it just felt good. Then a lit agent called me out of the blue and was like, "You should write a book about this," and I was like, "Absolutely I should write a book about this." I think if, in some levels, if he hadn't made that call, I'd still be putting out articles every couple of months as I dealt with new realizations.

ACH: So, I don't know if I'm done with this. I'll probably write more about it my entire life, just it's such a giant hurt and pivotal event in one's life that I'm never going to be like, "And now I'm done."

ACH: It'll always be there. So yeah, I don't really know. I don't understand the process. When the opportunity to write a book presented itself, I was like, "I need to do that," so I did.

KS: Yeah, definitely. You write in the book as well about the therapy that you went through, which is sounds some scientific, some ... I can't remember the acronym for it. It was-

ACH: EMDR [Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing].

KS: EMDR. I think that's super interesting. You've chosen many different avenues as a way of dealing with a lot of this grief and Lydia's suicide. What advice do you give to people out there who are maybe not feeling like one thing is working for them? How did you figure out the way to deal with getting over this? I mean, you'll never truly be over it.

ACH: No, just working through it better. I know what you're saying. There is no one path. I think mourning or grief or mental illness or maybe all of it is very personal. So, how you do it ... how I deal with it is different than how my sister deals with and it's different than how my mom and my dad, how you would deal with it. But I think an important thing to realize is that mental health is not a fixed place. You're not like this way, and that's how you're always going to be. It's something that you can work on. And whether that is you're depressed and you're suicidal or you're dealing with someone who's depressed and suicidal, or you're grieving. It's all this malleable ever-changing experience. And I think the more we realize that, the more you allow yourselves to go on the journey as long as it takes.

ACH: People always compliment people for working on their physical health. Like, "Hey, you're getting in shape. Good. You look good. You're eating right. You're exercising. Good for you." It should be the exact same with mental health. It's just like, "Hey, you're working on it. Good for you. You're seeing a shrink. Oh, you don't feel like you need to right now? Good for ya. You're doing yoga and hiking a lot, awesome. That gets your head in a good space." I think we just need to be very understanding of mental health being something that should be talked about and that's normal to be working on, and there should be no shame or stigma in that. Even just talking about it more, I think makes people feel more okay about it all.

ACH: That's why, I mean I'm not trying to be some sort of face of a cause or leader or pretend like I know more than anyone, but I do know that just me saying, "Hey I do therapy. I've done a lot of therapy." Told a couple therapists, "You're not working for me." Found some other ones. Just it's normal and good. We need to be better as a society by not being weird or mad about that. It's all quite normal.

KS: I like that, thank you. The last question I have, and I want to close with something towards the end of the book. At the end of the book, you were talking about a trip that you and your dad took to Europe and the compounding factor of grief and trying to get away, and then having all of your stuff stolen. Do you ever just sit back and laugh at those little mundane things, in comparison, life throws at you? How do you as a comedian just look at the comedy in life for what it is? How do you sit back and just find a sense of comedic joy in some of the little bullshit about life?

ACH: Yeah, I think there's this misconception of comics that they're always miserable gruff assholes, which they are, but they also find joy in the world. If they didn't find joy, they wouldn't go up there and share these little stories that delighted them. I think for me it's honestly ... I've taken this, like I've zoomed out and taken a world view of like no one knows why we're on the planet. It's a complete mystery. No one's positive if there's an afterlife or not. We could very much just get this 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80 years of life as a freak thing that we have consciousness for this small little blip in the universe. So, why spend the whole time being sad? Soak it up and laugh at it.

ACH: Obviously, it's easier to say than to do, but I really try to go through life wide-eyed. And even though you get hit in the face sometimes, you've still got to be like, "Oh man, that was rough, but I've got a lot of life left. There's a lot of interesting shit out there to see. So, I just try to cosmically think about how lucky anyone is to be alive and not waste it by being sad.

KS: Well, I want to thank you again for writing it and putting that all out there. Like I said earlier, coming from an upper middle-class white family that has struggled with depression and suicide, it's often taboo to talk about. It was so nice to see a story that just turns the topic on its head and lays it all out there.

ACH: Yeah, it's about mental illness, even in the seemingly best of scenarios, being able to rear its ugly head, which just shows how pervasive it all is. So, thanks man. I appreciate that. And thanks for reaching out and doing the interview. I appreciate it. Tell everybody at Audible thanks for the warm reception. It's been very cool.

KS: Oh absolutely, we really appreciate it too.

ACH: Yeah. Thank you.

KS: Have a good one.

ACH: Bye.